Logic a Loser in Arbitration Rulings

- Share via

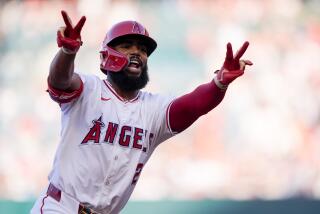

They are the only major league games likely to be played for some time, and the Angels are playing them the same way they usually handle the real thing. Win one, lose one.

Arbitration season opened this week with Mike Port taking on his two most talented players, Wally Joyner and Devon White, behind closed doors. Through the blood, the sweat and the tears, Port emerged with a hard-fought 1-1 split, losing to the first baseman before bouncing back in a big way against the center fielder.

Just as easily, though, Port could have gone 0-2. Or 2-0. The hows and whys of the arbitration process, like the Jose Canseco Hotline, are things that may be never fully understood or explained. Next to the coin toss in football, baseball arbitration has to be the most imperfect science in all of sports.

And the coin toss, at least, is governed by principles of gravity and physics.

Arbitration rulings tend to just happen, out of thin air and thinner logic.

How does Bo Jackson hit 32 home runs, drive in 105 runs, steal 26 bases and the 1989 All-Star Game . . . and come out of arbitration earning $400,000 less than Lloyd Moseby?

How does Joyner drop from .292 to .285 in batting average, from 85 to 79 in RBIs, from 176 to 167 in hits . . . and receive a raise of $830,000?

How does White win a second Gold Glove, steal 44 bases, earn a spot on the American League All-Star team . . . and walk away with less pay than pitcher Zane Smith, who won one game in 1989?

One game. Between Atlanta and Montreal last season, Smith went 1-13 in 17 starts and 31 relief appearances. For that, Smith will be paid $660,000 in 1990--or $80,000 more than White.

If he ever wins two, the Expos will have to raise ticket prices.

From this view, timing is the all-important constant in arbitration. Bo went first and lost. Joyner went next and won. Then came White. Yep, another defeat.

Anybody who thinks Joyner ought to be making $750,000 more than Bo this year, raise your hand.

Not you, Wally.

Bo should either get himself a new agent or a new ego. His arbitration figure was a cheeky $1,900,001, the extra dollar in place so Bo could claim to be better paid than Ruben Sierra. Sierra, of course, batted 50 points higher than Bo, drove in 14 more runs and had 90 fewer strikeouts. No player in the American League had a better season than Sierra.

So, with Bo, pride went before practicality. Realizing that he had filed far too high, his employers in Kansas City came in low, at an even $1 million. Had Bo been willing to settle for the humble sum of $1.5 million, or even $1.6 million, he probably wouldn’t have left with a smaller salary than Ernie ($1.2 million) Whitt.

Instead, Bo had to hang on to his moonlight with the L.A. Raiders for another year.

If Joyner had lost his arbitration hearing, he’d still have been earning $225,000 more than Bo. Wonder what might have happened if Joyner had been scheduled first. Or, if Andres Galarraga hadn’t just signed a three-year contract that will pay him $1.7 million in 1990. Galarraga, Montreal’s first baseman, batted .257 with 85 RBIs and 147 hits last season. Compare his numbers to Joyner’s and, sure, Wally deserves the same ballpark figure.

As it turns out, Joyner will make the same base salary in 1990 as San Francisco’s Will Clark. Clark batted .333 with 23 home runs and 111 RBIs last season. He was MVP of the National League playoffs. Many are starting to call Clark the best player in baseball.

Joyner is the best player in Anaheim.

No wonder Wally can’t stop smiling.

Consider Wally’s award retribution for past affronts, back pay due him after the shafts of 1987 and 1988. Without the leverage of arbitration, Joyner got beaten up and beaten down, beaten all around, following his first two outstanding seasons.

As a rookie in 1986, Joyner hit .290 with 22 home runs and 100 RBIs, led the Angels to the AL West championship and was narrowly outpointed by Canseco for AL rookie of the year.

In 1987, the Angels told Joyner to take $165,000 and be happy with it.

That season, Joyner had one of the greatest offensive seasons in Angel history--.285, 34 home runs, 117 RBIs.

The Angels renewed him at $340,000.

Last spring, Joyner finally gained arbitration eligibility. His salary jumped to $920,000. And this spring, Joyner finally took the Angels to arbitration. His salary nearly doubled.

This is why arbitration has become a focal point of the present Basic Agreement bargaining mess. The owners want to kill arbitration. The players want more of it, slicing the eligibility requisite from three full major league seasons to two.

With Joyner as the new case study, the players figure they’d be better off holding out until June than giving one inch on the arbitration issue. It can be exasperating; there are tales of arbitrators asking the definition of slugging percentages and save opportunities. It can be demoralizing; Gary Pettis once sat in on a losing session and took the obligatory slagging so personally, he sulked through all of spring training. But, from the players’ standpoint, it sure beats the alternative.

Even as losers, Jackson and White received hefty pay hikes. Jackson went from $610,000 to $1 million, White from $320,000 to $580,000.

Next up for the Angels: Kirk McCaskill, scheduled for Feb. 19 in New York.

Between then and now, McCaskill has to be hoping for a few more player defeats.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.