BOOMER: Railroad Memoirs <i> by Linda Niemann (University of California Press: $19.95; 252 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Linda Niemann had come close to hitting bottom when she saw an employment notice calling for brakemen on the Southern Pacific Railroad. A dropout from the academic life, she had sunk to calling herself a musician while “what money there was” came from dealing drugs, and that money mostly went on drugs and alcohol. One of the first women to sign up for the physically demanding work, Niemann saw railroading as a way to force herself to sink or swim: “By doing work this dangerous, I would have made a decision to live.”

Her harrowing initiation took place in the switching yard at Watsonville, Calif., through which passed all perishable freight from the “salad bowl” of America. Like Niemann, the reader is thrown into the middle of railroading, colorful technical terms flying in every direction with no attempted explanation. After all, Niemann writes, the “old heads” never try to explain anything to the beginners in words; the work is physical. Railroading work can be learned only with the body, so let the terms for the heavy iron pieces sink in as the muscles to work them harden.

Little did Niemann realize that her initiation was the softest imaginable. As she travels around the country--a “boomer” following the work as rush periods succeed one another in various railroad yards--she sees all manner of work, from the hell of Texas at the end of the oil boom to the petrochemical cesspool of the Strang yard, where trains called “bombs” are made up, named for the hazardous materials they carry. Hers becomes a world peopled by characters with nicknames like Cadillac and Wrong Way.

The most appealing parts of “Boomer” are the tough passages describing hard realities of life on the rails, written in a hardboiled-detective style (“A coffee cup sat there with a quarter-inch of what looked like diesel fuel in it. I guessed that is was cold and that he would probably drink it anyway”). Less engaging are Niemann’s discussions of dreams, wrestling matches with her sexuality and observations on Woody Guthrie’s “Bound for Glory.” But as an antidote for a wasted cerebral life, railroading was just what the doctor ordered for Niemann, and paradoxically with many words, she manages to convey to the reader a sense of redemption through physical labor.

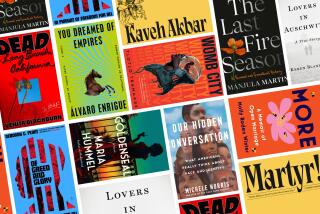

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.