The Post-Cold War Primacy of Economics : Tokyo summit may foreshadow shape of world relations

- Share via

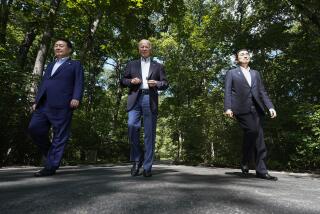

If the Tokyo summit achieved little new in terms of substance, it may have cast light on future superpower meetings in the post-Cold War era.

The summit between President Bush and Japanese Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa concluded with mixed reviews and disappointment, in large measure because it was misconceived from the start: The President’s handlers wantonly used the trip to mitigate political pressures on the home front.

Bush’s Pacific tour invited lofty expectations. He billed the trip as a quasi-trade mission to create “jobs, jobs, jobs” for Americans. If that weren’t enough, he was weighed down with executive baggage--18 U.S. business executives who went along in an effort to help open Asian markets, particularly in Japan. Even before Bush set foot in Japan, Administration spokesmen were blaming Tokyo for the U.S. recession--hardly the best overture for friendly discussions about trade and other economic issues.

SPECIAL RESPONSIBILITY: The foreboding about the visit took a startling turn when the President collapsed because of the flu during an official dinner with Miyazawa. He recovered quickly, much to the relief of all. But whether the U.S.-Japan partnership fully recovers from the latest face-off is another question. Bush and Miyazawa rightly concluded in their joint declaration that in “the post-Cold War . . . economic issues have assumed new prominence.” They also promised--”as the two largest market-oriented economies and democracies in the world”--to “accept a special responsibility for shaping the new era.”

How to shape that era clearly is another matter. Washington and Tokyo have a long way to go. Most of the measures they unveiled were widely predicted and were more face- saving than substantive. Auto makers were still grumbling that they didn’t get enough market access in Japan, although they only this week decided to produce cars with steering wheels on the right side for Japan’s market. As expected, Tokyo promised to buy 20,000 U.S. cars a year, increase purchases of auto parts, relax car inspection standards and boost imports of other U.S. goods.

FUZZY COMMITMENTS: The President and Miyazawa also agreed to jointly promote world economic growth by pumping up their domestic economies. But the commitments were fuzzy. Tokyo is targeting a low, but better-than-expected, 3.5% growth. The U.S. commitment was even more vague. Presumably Bush will be more specific when he delivers his State of the Union speech later this month.

And so Bush heads home, having acknowledged that more has to be done on the trade imbalance but still insisting “we have created jobs. . . . This visit has been a success.”

But the unhappy end result is that Tokyo is still managing access to its markets. Given the domestic political pressure that Miyazawa is under, that result was probably inevitable.

Although the summit gave the participants a chance to reaffirm their “global partnership,” trade differences are best addressed in a multilateral forum. In this regard, it’s worth remembering that the United States has not been alone in its criticism of Tokyo’s anti-competitive trade practices. As one of the world’s premier traders, Japan should be a leader in pressing for a successful conclusion to opening markets worldwide in the current Uruguay Round of the multilateral trade talks (GATT). A more open Japan would be welcomed by the entire world.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.