It Helped to Be Amateurs, Say Discoverers of Buried City

- Share via

Nicholas Clapp likes to say he stumbled onto the road to Ubar by way of a quirky bookstore in Westwood.

It was 1982 and Clapp, an Emmy award-winning documentary filmmaker, was looking for a particular book about the Arabian desert for a possible movie project. The tiny Egyptology bookstore, which has since closed, didn’t have what he sought, but the woman behind the counter said she had something better.

“She was a big, brusque woman,” Clapp recalled Tuesday, smiling as he remembered her first name. “You read what Virginia wanted you to read.”

So, Clapp read “Arabia Felix,” written in 1932 by the British explorer Bertram Thomas. In it, Thomas gave the coordinates of a road he believed led to the legendary city of Ubar, an ancient and, some believed, mythical metropolis. Intrigued, Clapp decided to investigate further, spending “maybe half a day” at the library.

Today, 10 years later, Clapp, 53, and George R. Hedges, the 39-year-old lawyer who helped him organize an elaborate expedition to Southern Oman, are celebrating their discovery of one of the great lost cities of antiquity.

They happily admit to being amateurs--Hedges holds a master’s degree in classical studies from the University of Pennsylvania; Clapp majored in 19th-Century American literature at Brown University. But they believe that their unconventional approach--and their willingness to ask “dumb” questions--are part of the reason they discovered what teams of academics had failed to unearth.

“There have been several unnamed Ivy League institutions that have been through there and missed the boat,” Clapp said in an interview at Hedges’ downtown law office.

“They begin with an H!,” Hedges chimed in.

Their mood hasn’t always been this giddy. As recently as six weeks ago, Clapp told his wife, Kathryn, a Los Angeles probation officer, that he thought maybe they were searching in vain.

By then, they had come face to face with deadly carpet vipers, camel spiders and giant ticks. They had survived stinging sandstorms and subsisted, in part, on surplus MREs (meals ready to eat) left behind by American troops during the Gulf War. And still, they had not found Ubar.

“I said, ‘If I knew (in 1982) what I know now, I’d never have done this,’ ” Clapp said, remembering a moment when he feared that his “obsessive craziness” about the project had been a decade-long waste of time.

Now, Clapp is thankful for that single-minded curiosity, which led him in 1983 to plead his case at the Huntington Library in San Marino, persuading them to give him access to their collection despite his lack of advanced credentials.

Hedges--hooked after Clapp “popped the Ubar question” over lunch at the Toluca Lake Racquet Club in 1984--said they set out to find scientists who had both traditional training and open minds.

“We were the dumb question people,” Hedges said. “We had a tremendous advantage because we are not professionals and we could pick a little bit from here and little bit from there.”

They assembled an eclectic team, all enthralled by the idea--very much out of fashion among traditionally trained archeologists--that religious manuscripts and legends might contain useful clues.

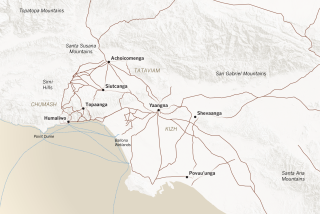

Using space imaging and ground-penetrating radar, they mapped out a network of ancient roads, many of them invisible to the eye. As they followed one they believed led to Ubar, however, they began to feel they were heading the wrong way--the artifacts they were finding amid the 600-foot dunes were neolithic, from the wrong period.

“The more we got out there, the more we realized it wasn’t out there,” Clapp said. “If anything, this was not the road to Ubar, but from Ubar.”

So they turned around, heading back to the tiny Bedouin settlement of Shisr, a site that three other expeditions had determined was no more than 300 years old. There, just before New Year’s Eve, they discovered Ubar, an octagonal fort and 10 square miles of camp sites dating back to 2000 to 3000 BC.

Hedges, who felt equal parts of joy and relief when the find was confirmed, says he has told his two young sons that there is an important lesson in Ubar’s discovery.

“You should do these things in your life. You should dream,” said the lawyer-turned-explorer. “Too often, people feel pigeonholed because they’ve chosen this career path or that.”

Clapp, who will be making a film after all about the expedition, nodded in agreement.

“But you know,” he mused, “we could have crashed and burned so quickly.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.