ARE WE GIVING TV TOO MUCH CREDIT?

- Share via

Who’s afraid of the big, bad TV?

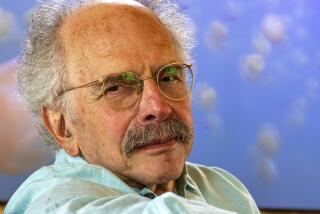

Not Douglas Davis.

Thumbing his nose at the video bogyman, this media contrarian has mounted a brave effort to set the record straight. The result is “The Five Myths of Television Power (Or, Why the Medium Is Not the Message),” published by Simon & Schuster.

“We have been told so often that television dominates our minds, lifestyle choices and political behavior that we believe the telling without conscious choice, without critical attention,” Davis writes.

How well Davis succeeds with his brand of critical attention isn’t really so important as the fact that he dares set out on such a lonely quest. After all, TV has been roundly dissed since Milton Berle donned his first evening gown.

Seductive. Isolating. Manipulative. Brain-numbing. These and other less-than-flattering words have become virtual synonyms for that gadget your mother told you not to watch so much of.

Pish-posh, replies Davis.

“TV is not omnipotent,” he writes, preferring to expose it as “an emperor unclothed.”

Here are the oh-so-popular assumptions that Davis disputes:

--TV controls our voting.

--TV has destroyed our students.

--TV is our reality.

--TV pacifies us, turning us into couch potatoes.

--We love television.

With statistics, Davis--a New York City-based author, artist and educator--blasts away at these precious myths, one by one.

According to Davis, the majority of voters who actually cast votes say that TV plays a minor role in influencing their decisions. He argues that bad schools, not TV, have destroyed the nation’s students.

If TV-bred fantasies dictate our “reality,” he wonders how come everybody watched the hard-core reality of the Clarence Thomas congressional hearings hour after hour? And if TV keeps us in its thrall, why are we reading more, traveling more and exercising more?

And finally, who do we know (besides maybe TV’s own Homer Simpson) who really loves TV?

On the contrary, we hate most of the TV we watch, according to Davis. For several years, most serious polling has confirmed an increase in the percentages of viewers dissatisfied with TV content, as well as those who say they are watching less, not more.

Just in time for the onset of 500-channel cable systems, Davis scoffs at “Brave New World” scenarios depicting people held at bay in their living rooms, happily incapacitated on video. The viewer, Davis writes, “knows precisely what is wrong, as well as what is right, with the drug that only appears to enslave him.”

Of course, there are statistics around for every occasion and argument. Take your pick.

For instance, disputing Davis are certain studies showing that up to 12 percent of viewers describe themselves as addicted to TV (watching an average of 56 hours a week, double the national adult average). These professed TV slaves report feeling unhappy watching that much, yet see themselves as powerless to stop.

In sum, Davis falls short of shattering the pesky myths he takes on. But where his book proves useful is not by proving innocence, but by raising lots of reasonable doubt (including, in a delicious passage, howling doubts about the Nielsen ratings).

His book reminds the reader how TV, with a certain demonstrated prominence and power, becomes susceptible to public fears of unlimited prominence and power.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.