America’s Oldest 4th : The historic town of Britol, Rhode Island, pulls out all stops for its long-running Independence Day celebration

- Share via

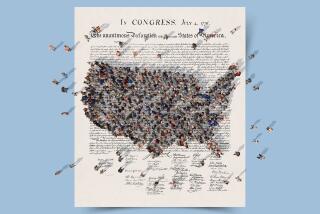

BRISTOL, R.I. — My friends Ruth and Jack Connery, who live down the street from me in this historic town, just had their house painted. When they contracted for the work, they included a standard local proviso: The job had to be done by the Fourth of July. In Bristol, plans revolve around July 4 the way plans in other American communities revolve around Dec. 25 or Super Bowl Sunday. Our town’s Independence Day observance, which dates from 1785, is believed to be the nation’s oldest, and its annual return is celebrated in a big way.

Events--a beauty contest to choose the queen, a fireman’s muster, block dances, boat and running races, a greased pole climb, band competitions, a carnival and fireworks display among them--last more than a week. But the celebration reaches the top of the flagpole on July 4 (or July 5, in years such as this when the Fourth falls on Sunday). This year, Bristol’s Independence Day parade will once again high-step through town for more than two hours, dozens of brass bands blatting, platoons of politicians shaking hands, and flotillas of floats gliding proudly under the auspices of local supermarkets, auto dealers and restaurants.

It’s all part of the spectacle that regularly draws some 200,000 visitors to join 22,000 of us locals in celebrating the Fourth. Out-of-staters quickly fall for the Norman Rockwell charm of Bristol, located midway between Providence and Newport on the eastern side of Narragansett Bay. Clapboard houses with National Register plaques and lacy fanlight windows line the parade route. Some of the homes’ gingerbreaded porches and carved eagles were the work of ships’ carpenters, for this has always been a town of boats and boatwrights, sailors and fishermen.

The 2.8-mile parade route forms a “U,” following Hope Street, the main thoroughfare through downtown, passing a seawall at the edge of the bay, then looping onto parallel High Street, where I live. By the time the high school bands and members of Congress pass my house on High Street, a few blocks from the end of their effort at the Town Common, they’re drooping slightly but respond with enthusiasm to neighborhood cheers.

Last year there were about 100 strangers outside my house to cheer the passing parade: a team of Clydesdales sponsored by Hallamore Trucking, a color guard sent by the state prison, the head coach of the Bristol Wrestling Club, Frenchy the singing barber waving regally from a convertible, an onslaught of environmentally active children carrying signs urging “Stop Junk Mail,” and much, much more. Eleven divisions passed my house, each assigned a theme like “Liberty” or “Bill of Rights.” The “Freedom” division exemplified American diversity, juxtaposing the Knights of Columbus, the New Bedford High School Band, a solar-powered automobile, a 1926 Ford Model T delivery truck sponsored by a bakery, and a graciously waving Miss Rhode Island, Lisa Snow.

Some regular spectators have made themselves as much a part of parade tradition as the town’s old firetrucks and post office vehicles. Take Gerrie and Mickie MacNeill, who live across the street from me. About 10 years ago, Gerrie, whose Old Testament white beard owes nothing to adhesive, began wearing a cardboard Uncle Sam hat to the parade. Over time, other elements of a Yankee Doodle wardrobe came into his possession, and on July 4, Gerrie now transforms himself into Uncle Sam from head to toe.

His wife Mickie concedes, however, that they probably went too far the year she dyed his beard with red and blue stripes and stuck gold stars in it. Too messy to get out. Mickie herself is a bit more subdued. She just dresses up like Betsy Ross.

Charlene Vernon, a.k.a. “The Parade Lady,” arrives from her home in nearby Warren, R.I., wearing something uniquely patriotic every year; one of her most memorable costumes was worn in 1991, when she was a Patriot missile, in honor of the Gulf War weapon.

Then there’s “The Living Flag: Six Festive Americans,” former spectators who have become official marchers, thanks to the ingenious costumes designed by Marilyn St. Ours. A professional artist, St. Ours creates the designs that her father reproduces in his tattoo parlor. Her Independence Day creation is a human flag, its stars and stripes spray-painted in segments on six white T-shirts and six pairs of pants. The shirts and pants are worn by St. Ours, who identifies herself as “the short, striped one on the end”; her husband Andrew, who portrays the flagpole with an eagle finial on his head; Marilyn’s sister, and three friends.

They first unfurled their flag several years ago as spectators standing in front of a friend’s house on the parade route. They made such a hit that they were asked to become an official part of the parade, right in there with the Coast Guard’s lighthouse float, the Rhode Island State Troopers, the submarine veterans and a mysterious dark-haired lady identified in last year’s program as “Rhode Island’s Most Beautiful Woman, Tina Cordeiro.”

Since then, the flag people have gone on to march in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade and to greet George Bush when he arrived in Rhode Island for a visit before the 1992 presidential election.

Bristol was settled in 1680 and became a flourishing maritime and commercial center in the 18th Century. The first Bristol-built merchant ship was in operation as early as 1686, but it was the slave trade and privateering that enriched the early captains. It’s said that when the War of 1812 began, Bristol had a fleet bigger than the new U.S. Navy. Most local ships went into government service then as privateers, civilian vessels authorized by the government to capture and destroy enemy shipping, for profit.

Before that, Bristol was the scene of Revolutionary activity. In 1777, a British officer recorded that “This being the first anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in the Rebel Colonies,” Bristol ushered in the morning by firing 13 cannons, one for each colony, then repeated the salute at the end of the day. “As the evening was very still and fine, the echo of the guns down the Bay has a grand effect.”

But Bristol’s claim to the long-established Independence Day celebration dates only from 1785. That year, the date was marked by a religious service giving thanks for the town’s survival after being burned by British Redcoats and Hessian mercenaries in 1778.

So does that prove Bristol has the country’s oldest Fourth of July celebration? “As far as I know, we’ve never been challenged,” says Helen Tessler of the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society. Then she added slyly, “If you keep repeating something long enough, it becomes fact, doesn’t it?”

Bristolian Richard V. Simpson probably knows as much about the celebration as anyone does. He’s the author of “Independence Day: How the Day Is Celebrated in Bristol, R.I.,” the definitive history of the observance. His book is packed with anecdotes about the triumphs and disasters of past Bristol Fourths, from 1897, when a boy blew up a fireworks stand, to the injuries sustained the following year by Charlie Elder and Charlie Duffie through careless firing of their revolvers.

Even worse occurred in 1854, when several houses and the Baptist Church were set on fire by carelessly discarded firecrackers and gun wadding. According to Simpson’s research in the files of the Bristol Phoenix, the weekly paper that’s still the town’s primary local news source, a 12-year-old “lad named Morris” saved the Baptist Church by climbing to the roof and extinguishing the flames. When stamping and spitting on the fire proved inadequate, “he had the presence of mind to unbutton his pants and play his own engine so effectually that he entirely extinguished the flames.” Young Morris descended to “loud huzzahs.”

But not even historian Simpson is sure when Bristol’s annual parade began. He suggests it may have begun as a procession to the church for the patriotic exercises. That there were parades as early as 1826 is known, but their year of origin went unrecorded.

No matter how the Bristol celebration originated, it surely has caught on. Planning goes on all year, with a committee of more than 100 Bristolians sharing the workload. In June, the town steps up the pace. Houses get painted, roofs get fixed, porches get new rockers or fresh paint for the old ones. Lawns are clipped and brush is cut, flower beds and window boxes suddenly overflow with red, white and blue petunias. Andrade’s Catch and other fish markets sell enough quahogs to replicate the harbor in chowder. Hot dog rolls? If you didn’t shop early and stuff the freezer, forget it. This is Bristol’s big party day, a combination of family reunion, homecoming and “We’ve invited a few friends to watch the parade.”

Bunting orders flow into Ebenezer Flag Co. weeks beforehand and flags come down from attics. On July 4, Bristol becomes a gallery of banners, a museum of flags: bright flags, faded flags, garish new ones and tenderly preserved antiques, wool flags, silk flags, flags flown on ships and over the U.S. Capitol. There are vast flags that cover the sides of two-story houses, and ranks of tiny flags marching across front lawns. A house-decorating contest inspires homeowners to crepe paper creativity; they swath doors, shutters, gates and garages in enthusiastic imitation of Old Glory.

In the wee hours of an unannounced date in mid-June, colorists from the Bristol Public Works Dept. repaint the red, white and blue stripe down the middle of Hope and High streets, the parade route. Bristolians care intensely about such details as the shades of paint used. I remember seeing a friend standing in his front door last year on the morning when the fresh stripe appeared. He looked dismayed. “Powder blue,” he said. “All wrong.”

The first-time visitor should plan to arrive early, as much as a week before the holiday, in order to sample the pleasures of Bristol and the East Bay. The few accommodations in and around Bristol are often booked well in advance of the Fourth, but Providence and Newport offer a wide choice of places to stay. Seafront Newport, half an hour’s drive from Bristol, is more appealing in summer than Providence, at the head of the bay. Newport’s fabled Gilded Age mansions are open for tours, beaches are busy and the night life of the waterfront is at its best.

And Bristol itself has lots to see on a non-holiday.

This was the site of the world-famous Herreshoff Manufacturing Co., designers and builders of beautiful sailing yachts, including those that won the America’s Cup eight times between 1893 and 1934. The popular Herreshoff Marine Museum on Burnside Street displays 35 classic sail and power yachts dating from 1859 to 1947.

Other points of interest to visitors include the Linden Place and Blithewold mansions and the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology.

The Haffenreffer, donated to Brown University 40 years ago by a family of that name, is devoted to study of the earliest Americans. It features exhibits of archeological and ethnographic material from North America and traditional art. Exhibits on native traditions of southeastern New England and the work of Tomah Joseph, a Pequot birch bark artist, continue this summer.

Blithewold Mansion and Gardens, on the south end of Hope Street near Mt. Hope Bridge, was built in 1908 as the summer estate of Pennsylvania coal baron Augustus Van Wickle. The 45-room stone house on 33 landscaped acres at the edge of the bay is Bristol’s cousin to the Newport mansions. Decorated and furnished as it might have been early in this century, it is open for tours.

Bristol’s oldest houses are north of downtown in a section called The Neck. Among them are the Deacon Bosworth House, the earliest house in town, where religious services were held as early as 1680, and the Joseph Reynolds House, where Lafayette established his headquarters in 1778, when he arrived to help defend the area against the British. Most old houses downtown date from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Our town’s greatest architectural treasures are the work of the 19th-Century architect Russell Warren, whose masterpiece is Linden Place, one of the most elaborate Federal houses in New England. It was built in 1810 for the flamboyant George DeWolf, who made a fortune in the slave trade, then went broke. With bankruptcy looming, he loaded his family onto one of his ships in a snowstorm and sailed for Cuba, owing money to half the people in town. The story is that his enraged creditors ransacked the house.

Unlike most of Bristol’s other historic houses, DeWolf’s mansion, now restored, is open to the public. It’s owned now by the nonprofit group Friends of Linden Place, whose fund-raising events include an annual clam cake and chowder picnic on parade day. For the price of the ticket ($25 per person), visitors can feast on clam chowder made by Bristol’s own Gerd Serbst, the state’s champion chowder-maker, and clam cakes--those hot, quahog-studded fritters that true Rhode Islanders are able to devour by the dozens--while watching the parade from a shady lawn in the heart of downtown.

Chowder will also be served at family cookouts and picnics all over town, along with the fennel-flavored Italian sausages and garlicky Portuguese chorizo that have become universally popular in this ethnically diverse community. One of the longest-running Independence Day parties is hosted by my friends the Connerys, whose newly painted house stands ready to greet “a few friends”--250 of them showed up one year--who usually drop in. Ruth inherited the event from her father; she and Jack have hosted the bash for nearly 30 years.

The Connerys’ tables are laden with their ham, turkey, hot dogs and my personal favorite, a dish of chorizo sausage slow-cooked with peppers and tomatoes that Ruth makes each year. Friends bring salads and casseroles, homemade bread, hamburgers, cakes and pies. We eat, drink, applaud the Fralinger String Band’s mummers, cheer the grand marshal and his 100 or so aides, pass the mustard, thank the ex-prisoners of war, admire the 1932 Hupmobile coupe, and dance along with Tom McGrath’s Clambake Band.

If you haven’t been invited to one of these parties, street vendors can help assuage your hunger. But some people have been known to invite themselves. Ruth Connery remembers having a pleasant conversation one year with a rather proper matron who had just emerged from the upstairs bathroom.

“She was awfully nice,” Ruth told Jack. “Who is she?”

“I thought you knew her,” Jack replied.

In Bristol, R.I., Yankee Doodle Day is dandy.

GUIDEBOOK: Doing the Bristol Stomp

Getting there: Bristol is about 50 miles south of Boston, between Providence (15 miles north) and Newport (14 miles south) on the East side of Narragansett Bay. The airport serving Providence is in Warwick; airlines offering flights from LAX are USAir, American, Contintental and TWA. Bristol is about a 45-minute drive from the airport.

Where to stay: In Bristol, the Rockwell House Inn (610 Hope St., Bristol, R.I. 02809, 401-253-0040), is a bed and breakfast in a commodious pink Federal house on the parade route. Summer rates: $75-$100. The Ramada Inn (144 Anthony Rd., Portsmouth, R.I. 02871, 401-683-3600) is just five minutes from Bristol. Summer rates: $69-$100. (Both hotels require a minimum two-night stay during the Independence Day festivities.)

In Providence, the Omni Biltmore (11 Dorrance St., Providence, R.I. 02903, 800-843-6664 or 401-421-0700) is a local landmark, an updated version of a grand old hotel, whose bathrooms still have tubs deep enough to accommodate William Howard Taft. Rates: $99-$119 for a double. The hotel is half a block from Bonanza bus connections to Boston and Rhode Island Public Transit buses. RIPTA buses leave hourly for Newport with stops in Bristol.

Newport offers a wide choice of accommodations, from full-service hotels to bed and breakfasts in historic houses. The 253-room Newport Islander Doubletree (Goat Island, Newport, R.I. 02840, 800-222-8733 or 401-849-2600) offers glorious views of Newport’s yacht traffic; doubles are $159-$254. One of Newport’s most attractive bed and breakfast inns is the Sanford-Covell Villa Marina (72 Washington St., Newport 02840, 401-847-0206) in Newport’s historic Point section. Built in 1870 as a summer cottage for industrialist Milton H. Sanford, it has a 35-foot-high entrance hall, handsome waterside pool and a view that stretches from the graceful Newport Bridge to Goat Island. Rates: $99-$119 for two (includes breakfast and evening port or sherry).

Where to eat: Restaurants in Bristol offer a range from fresh local seafood to the Portuguese and Italian dishes that arrived with immigrants from those countries. S.S. Dion (520 Thames St., local telephone 253-2884) on the waterfront is the best choice for Block Island swordfish, lobster and other seafood. The dining room looks like the solid-citizen restaurants your parents favored; a deck overlooks Bristol Harbor and Poppasquash Point, where Clinton health-care adviser Ira Magaziner lives when he’s at home. Dinner entrees: $9.95-$19.95.

Another local favorite is the Sandbar, a couldn’t-be-plainer eatery on the water (775 Hope St., tel. 253-5485) just north of town. Smoky, noisy and busy, the Sandbar serves a plate of seafood zuppa--pasta with steamed seafoods in a light sauce that by itself is worth the trip to Bristol. Other faves are the fish and chips and Portuguese baked fish in a fennel-scented tomato sauce. You’ll dine at the Sandbar for less than $10 a person, including a glass of jug wine.

For chowder and clamcakes, I favor the takeout at Andrade’s Catch (186 Wood St., tel. 253-4529), whose clamcakes are packed with chopped clams. Also, try the fish and chips ($3.70 regular size, $4.80 large), classic Rhode Island fare that came with the English mill workers. Redlefsen’s Rotisserie (425 Hope St., tel. 254-1188) has contemporary cuisine: seafood cioppino , grilled trout, and always a few German dishes, including a sublime schnitzel. Entrees, $7-$17.

For more information: Contact the Rhode Island Tourism Division, 7 Jackson Walkway, Providence, R.I. 02903, (800) 556-2484.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.