Gateway to . . . the Majors? : Billy Hatcher’s Hometown Isn’t the End of the World, but You Can Reach Grand Canyon From There

- Share via

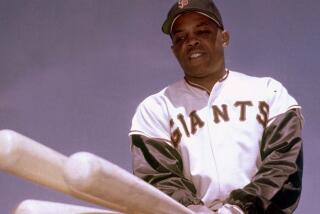

WILLIAMS, Ariz. — There are fewer kicks on Route 66, a weakened artery since the interstate bypass, but the old cow town refuses to die. It rises each morning to peddle its turquoise trinkets, pour its mountain-roast coffee, point visitors to the Grand Canyon and scour the box scores in search of Billy Hatcher, its first and probably last hometown hero.

Gracie Hatcher’s boy. Five forty-one West Sherman. Lived around the corner from the Turquoise Tepee. Everyone lived around the corner from the Turquoise Tepee.

Batting .287 as center fielder for the Boston Red Sox.

Little Billy Hatcher.

Used to pull best friend Steve Maestas out of bed at 5 a.m. and drag him trout fishing on mirrored waters at the Santa Fe Dam in the heart of the Kaibab National Forest.

Would walk into the Maestas’ house, always unlocked--isn’t everyone’s?--tiptoe into Maestas’ room and yank the sheets.

The Billy Hatcher Apple Dumpling Gang.

Used to “borrow” the life-size porcelain cow in front of Rod’s Steakhouse and move it in front of the Coffee Pot diner.

Moooooo fun.

Would circle the two one-way streets on the only main drag, known as the Idiot Loop, wait for the attendant at the Standard station to fall asleep, then hitch a rack of new tires to the back of a pickup and relocate them down the street.

When the guy woke up?

Huge laughs.

Just another day in the life of Williams, home to flashing neon storefronts, the Sultana Bar (“Booths for Ladies”) and the Grand Canyon Hotel, outside of which a faded vacancy sign hangs and another offers rooms to let for “$3.50 and up.”

This is Williams, the population of which has doubled to 2,600 since . . . 1901.

This is the shortest route--about 60 miles--from Interstate 40 to the south rim of the world’s seventh wonder. The town owns the trademark, “Gateway to the Grand Canyon,” so don’t even think about it, Ash Fork.

Williams, home to the “Billy Hatcher Omelette” at Old Smoky’s Pancake House.

Williams, named after Bill, the 19th-Century pioneer. Founded in 1880. Nestled in the pines at 6,700 feet. Was once a booming railroad, lumber and cattle town.

Survived calamitous fires, mill closures, opium dens, Wild West outlaws, railway failures, gas crises and what the government would call “progress.”

Fill the Grand Canyon with sand and you’re looking at a ghost town.

“It should have died,” Nancy Samson McDougall, a Williams resident since 1936, said of her town.

Williams clings to the Canyon for subsistence and to Billy Hatcher for deliverance.

In September of 1989, 21 years after the steam train to the canyon was discontinued because of financial difficulties, the Grand Canyon Railway reopened on the 88th anniversary of the first run in 1901.

More than 300,000 travelers have been served since, chugging new life into the town of 30 motels and a thousand rattlesnake artifacts.

“You can go places even if you grow up in Williams,” John Cardani, a longtime friend of Hatcher, said.

Easy to say now.

His teacher at Williams Middle School smiled and patted Billy on the head when he wrote in an eighth-grade essay that he would grow up to be a big league baseball player. In the same assignment, Cardani vowed to become a police chief.

Hatcher is finishing his eighth full season in the majors. Last year, Williams swore in a new chief of police.

Guy named Cardani.

*

It is not a town without pity.

Someone was killed here five years ago, a woman who worked at the Cornet five-and-dime. Left in a shallow grave outside town. The murder remains unsolved.

“Everybody knows who did it and everybody’s wrong,” said McDougall, the unofficial town historian. “She was last seen drinking beer with somebody and next thing you know, she’s gone.”

Last year, Danny Ray Horning, an escaped convict, eluded capture near Williams with Rambo-style survival techniques. Ran so fast the hounds couldn’t catch him.

The townsfolk dubbed the locals in pursuit “The Barney Fife Patrol.”

This did not, however, dissuade residents from leaving their doors unlocked and their keys in the cars.

Many was the morning Maestas awoke to find his truck gone. No big deal. Hatcher borrowed it often to run errands.

Maestas took similar liberties with the Hatchers.

It’s true that Williams could smother you after you finished high school, unless you aspired to work in tourism or forestry.

But it is difficult to imagine a finer place to be a kid.

“To tell the truth, I couldn’t have picked a better place to grow up,” Hatcher said recently. “Everybody watched over you. It was one big family.”

Many who moved away from Williams, vowing never to return, later moved back to raise their families.

“It’s a magnet,” Police Chief Cardani said.

Lori Mitko moved here last year from Garden Grove. Her husband, a policeman in Bell Gardens, commutes 820 miles, round trip, each weekend.

The first time someone waved to Lori from a car in Williams, she instinctively ducked. Now she lets her children play outside after dark.

In Williams, you cannot distance yourself from what’s happening.

“When you see kids in auto accidents, you know them,” Cardani said. “When someone has a terminal disease and dies at home, you know them. When you make an arrest, you know them. That makes it hard.”

Gracie and Harold Hatcher raised 11 children in Williams. Plenty of room to grow but no place to hide.

“It’s hard to go to the bathroom without someone knowing,” Matthew Spieler, managing editor of the weekly Williams News, remarked.

The town boasts eight full-time police officers, 21 firefighters and age-old problems.

A hundred years ago, the town’s chief concerns were water, sewage and the streets.

“Today,” McDougall chuckled, “The problems are water, sewage and the streets.”

In Williams, parents are the gatekeepers.

Cardani’s father read meters for the electric company and knew every address from Williams to Seligman.

“My dad would sit on top of an electrical pole and see if we were ditching school or doing something we weren’t supposed to do,” Cardani said.

There are no gangs in Williams.

Spieler, a native New Yorker, clips the police blotter from the paper and sends it home to his mother, who reads it behind a bolted door.

July 12: Report of a dog bite occurred near the corner of Grand Canyon Blvd. and E. Edison. Victim was treated at the Williams Medical Center. Owner of the dog, Bob Burlington, was cited for dog at large, no city tags and no rabies vaccine . . . . With a population mix that includes 59% white, 26% Latino, 4% black, 3.8% American Indian and 2.7% Asian, there appears to be an absence of prejudice in Williams.

Arizona, you may recall, lost a Super Bowl because of its refusal to observe a holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr.

Williams is an eclectic enclave, though, a melting pot, a town built with cheap labor by people of many colors. The Chinese came in the 19th Century to work on the transcontinental railroad. Latinos and blacks were recruited to work in the lumber mills.

Hatcher’s grandparents on both sides came to Williams in the 1940s from Louisiana because there was work to be had.

Harold Crane, who ran the Haining Lumber Co. and wore expensive silk suits, used to scour the South for laborers.

The lumber industry has pretty much gone south itself, yet many families settled in Williams and stayed.

Colors never mattered much.

Billy Hatcher was black. His best friend, Maestas, had a Mexican father and an Anglo mother. Jimmy Luna, another close friend, was a Latino.

They lived within a block of each other and grew up like brothers.

“He and I never got in a serious argument, and never a fistfight,” Maestas said of Hatcher. “He has secrets that nobody else knows. His mom was my mom. When his dad died, it felt a lot like my dad dying.”

Save the isolated incident, the Hatchers and others walked the streets unencumbered.

“Every place you go, you’ll find some racism,” Gracie Hatcher said. “But it wasn’t that bad. The people are caring. We care for each other. It doesn’t matter what color they are.”

Last winter, as Billy’s father, Harold, lay dying of lung cancer at Prescott Veterans Hospital, the people of Williams chipped in to pay for Gracie’s gasoline so she could make the 68-mile trip to Prescott four times weekly. Harold Hatcher died on March 18, at 60.

A Korean War veteran, deacon and Sunday school teacher at Galilee Baptist Church, Harold was a pillar in the community, liked by all.

“All the people of Williams who knew him,” Gracie said. “They were so concerned. They gave me uplifting talks. They’d stop me on the street and tell me they were praying for me. A good many of the townsfolk came down to see him.”

Billy was the baseball star, but Harold Hatcher loved his children equally. It didn’t matter that five were from Gracie’s previous marriage.

That he died less than a month before his son set forth on his finest season might seem cruel to those of little faith.

Billy Hatcher was hitting .300 or better for much of the season and still is 24 points higher than his lifetime average of .263.

“Who’s to say he’s not watching?” Gracie said of Harold.

Billy, devastated by his father’s death, returned home from spring training in Florida to attend the funeral.

July 28, on what would have been Harold’s 61st birthday, Billy and his mom had a long cry over the phone.

The family asked doctors not to tell Harold that his cancer was incurable. Behind the scenes, Billy and Johnny, his sometimes stubborn younger brother, demanded answers and cures for their father.

It was straw-grasping.

Everyone eventually knew what even Harold knew.

Gracie vowed not to watch her husband go.

“I did not want to see him take his last breath,” she said. “But I was right there with him. It was the first time I saw someone pass. I was afraid. But I would like to go like he did. It’s not as horrible a thing as people tell you.”

Harold Hatcher was buried in the town cemetery, in the company of tall pines, about a 10-minute walk from his front porch.

In Williams, you do your grieving and then get on with living.

It is the makeup of a town that has faced many 1O-counts. In 1940, the Saginaw Lumber Co. moved to Flagstaff, taking jobs with it. In the ‘70s, gas shortages choked the flow of tourists to the Grand Canyon.

On Oct. 13, 1984, Williams became the last town on “Old Route 66” to be bypassed by the Interstate. Bobby Troup, who wrote the song, “Route 66,” came to Williams to sing it on that fateful day.

Great. Last rites with a back-beat.

What now?

Well, that same year, Billy Hatcher broke into the majors with the Chicago Cubs.

Morning had broken again in Williams.

*

It is difficult to calculate the odds of someone rising from Sherman Street to the big leagues.

Surprisingly, many in Williams say they knew Billy Hatcher was the real thing, not just a local phenom.

Maestas played against Hatcher in Little League and was his teammate in three sports at Williams High.

“He had what I still call his magic,” Maestas said. “Billy has more talent than anybody I’ve ever seen.”

Hatcher, 5 feet 10 and 190 pounds, was all-state in football, basketball, baseball and track.

During his senior year, 1979, the Williams High baseball team was competing in a semifinal playoff game in Phoenix on the same day the state track finals were being held at virtually the same site.

“You could hear the loudspeakers for both events,” said Maestas, a former Williams second baseman. “(Hatcher) would get up to bat, play an inning, switch clothes, jump a 6-foot fence and run track in 105-degree heat. He won the state 100. He’d run back and forth between innings. He did in one day what would be unheard of for us. It was the kind of thing you see on TV.”

Football may have been Hatcher’s best sport--he was a running back and safety--but he feared the injuries--not the ones he might suffer, the ones he might inflict.

“In football, I just wanted to hit them as hard as I could,” he said. “I wanted to hit them so hard so they wouldn’t get up. That’s what started to scare me. I figured it was time to get out.”

Hatcher elected to play baseball at Yavapai College, a junior college in Prescott, where he became an All-American and later, in 1981, a sixth-round draft choice of the Cubs.

The only athlete approaching Hatcher’s skills in Williams was his younger brother, Johnny, who lacked only Billy’s temperament and discipline.

Said their mother: “Billy and Johnny were only two years apart, but they were miles apart.”

Johnny Hatcher had a stint in the minors and now coaches high school football in Winslow, Ariz.

“He was thick-headed,” Maestas said of Johnny. “Johnny was a diamond in the rough. Billy was the finished product. Johnny was headstrong, not just about sports, but about everything. He was rush in and think later.”

Billy and Johnny, competitive as sharks, remain close.

“I marvel at their relationship,” Maestas said.

But it is Billy Hatcher who carries the Williams mantle.

The town newspaper does not subscribe to a news service, so Spieler of the Williams News relies on television and newspaper clippings to provide regular reports on the hometown star.

Until this season, Hatcher’s biggest highlight had been a flash-in-the-pan performance in the 1990 World Series, when he set a Series record with seven consecutive hits to help lead the Cincinnati Reds’ sweep of the Oakland A’s.

Williams staged “Billy Hatcher Day” soon after.

Gracie Hatcher, a baseball mom who grew up idolizing the Brooklyn Dodgers’ great teams, still can’t believe she can turn on the TV and see her son in center field.

“I dreamed of going to World Series games,” she said. “And the first one I went to, my son was playing in it.”

Hatcher’s career has been solid, not spectacular. Boston is the fifth team he has played for since 1984, the Red Sox having acquired him from Cincinnati for pitcher Tom Bolton in July of 1992.

Maestas is surprised Hatcher hasn’t had more seasons like 1993.

“He always had magic,” Maestas said. “I watch him on TV and I see it trying to come out again, and it doesn’t quite mature. Kind of like it’s been stumped.”

Hatcher, 32, lives in Cincinnati with his wife, Karen, and two children. He usually returns to Williams two or three times a year.

“I go to a bar, a restaurant, and it’s no big deal there,” Hatcher said. “It’s just, ‘There goes Billy, same old Billy.’ ”

His mother worries that her son won’t come home, now that his father has died, that it will be too painful.

Others hope the better memories will bring him back.

“It was a lot like ‘The Andy Griffith Show,’ ” Maestas said of life in Williams.

Times staff writer Bob Nightengale contributed to this story.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.