They Forget How Good McHale Was : Pro basketball: Celtic wasn’t in same category as Magic, Bird or Jordan, but he was a phenomenal low-post scorer.

- Share via

BOSTON — In Boston, Larry Bird was setting up easy layups by threading half-court, behind-the-back passes. In Los Angeles, Magic Johnson was closing his eyes, turning his head and lofting sweet, underhand alley-oops for his forwards to jam. This was the NBA of the 1980s, a decade defined by two master passers, one on each coast.

Bird led the Celtics to three NBA championships. Johnson won five with the Lakers. Together, they dominated the game while ushering in an era of unselfishness, in which players were ultimately judged by the answer to this question: Does he make his teammates better?

In this setting, Kevin McHale played out his career. Kevin McHale, who never met a pass he didn’t like--as long as he was on the receiving end. Kevin McHale, who never met a shot he didn’t like--as long as he was on the shooting end.

Kevin McHale, who may have been the most lethal low-post scorer in basketball history.

Already, it’s almost easy to forget how good he was. Why?

In the era of the master passers, McHale was both blessed and cursed: Blessed to be the recipient of Bird’s offerings, cursed to be in Bird’s shadow; blessed with unique ability, cursed to be an amazing scorer when superstars were measured by their court vision.

On top of that, McHale has never paid much mind to where he might be placed in history. No offense, but he has other things to do.

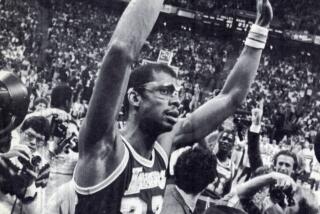

McHale retired May 5, 1993, moments after he and the Celtics were eliminated by the Charlotte Hornets in Game 4 of their first-round playoff series. His No. 32 was retired on national TV Sunday at halftime of the Celtics-Phoenix Suns game.

These days, McHale, 36, works for the Minnesota Timberwolves as a special assistant coach and broadcaster. He has been spotted on national television, headphones in place, eating an ice-cream cone on air. Invariably, one of his five children is seen sitting next to him; the kid, too, wears headphones and is eating ice cream. Life is pretty good.

McHale wanted to win titles. He wanted to have fun. He managed.

He still can’t believe he never had to work for a living.

*

He grew up in Minnesota, which borders Canada and is known for its beautiful lakes, sprawling dairy farms and dark mines. More specifically, McHale was reared in Hibbing, a city of 22,000 that has spawned the likes of Roger Maris and Bob Dylan.

In his youth, McHale was like every other lad in Hibbing; he figured he could kill time playing hockey until he had to get a job. Then, he would follow his father into the iron mines. No big deal. Indeed, McHale never thought about playing basketball at any level until he was 13, when he was a mere 5 foot 9. By the time he was 18, he was 6-10. Even as he sprouted, basketball remained just another way to occupy his time. He preferred hockey, which, as it turned out, was like Dylan opting for electric over acoustic.

When McHale led his high school team to the state championship game, college basketball coaches were just beginning to notice him. When the tardy scholarship offers were tendered, McHale counted himself lucky merely to postpone his job search until after he enjoyed himself in college.

As McHale once recalled, this was the way he made his decision to go to the University of Minnesota: “One day I just told my parents I was going to school and they said, ‘Oh good, we’ll be able to watch you play.’ I thought it was great to get a scholarship. My parents wouldn’t have to pay and, better than that, I wouldn’t have to take out all those student loans and be broke.”

After starting for the Minnesota Golden Gophers for four years, McHale was widely known among NBA general managers. The Knicks were hoping to select McHale with the 12th pick in the 1980 draft. Wishful thinking. The Celtics had the No. 1 pick and wanted a big man. They traded their top pick to the Golden State Warriors for Robert Parish and the No. 3 pick, which the Celtics used to take McHale.

This deal was probably Red Auerbach’s greatest swindle. The Warriors wound up with center Joe Barry Carroll, who, at one point, had a good season in there somewhere--it’s just that nobody can recall. The Celtics wound up with two future Hall of Famers to put in the front court with Bird, a fair player in his own right. Perhaps the greatest frontcourt in the history of basketball had been assembled. Instantly, the Celtics were a power lode.

The Celtics had invented the sixth man, the idea being that a potent scorer off the bench could rip the heart out of a tiring opponent. McHale was perfect in the role. He went on to become the best sixth man of his generation--during a time when important reserves were ripping off sweats all over the league. His scoring average improved in each of his first six seasons.

“Making him the sixth man and selling him on it was important,” said Bill Fitch, the Celtic coach McHale’s first three seasons. “You’ve got to have those bench points and have them every night. Kevin got them.”

K.C. Jones, with a laissez-faire approach to coaching veterans, led the Celtics to titles in 1984 and ’86. In those years, on into 1987, McHale was at the peak of his skills. After seven pro seasons, he had developed a low-post game that featured a litany of previously unseen moves. It is not a stretch to say that the assorted drop steps, head fakes, pump fakes, baby jump hooks, shovels and fadeaways that now proliferate the frontcourt play began largely with McHale.

“No one can guard Kevin,” Bird said, “especially in the playoffs.”

His arms were long enough to tie his shoes without bending over--and those arms were perhaps his greatest asset. McHale’s wingspan, on his 6-10 body, has been estimated at 8 feet. Most adult wingspans average 2-to-3 inches more or less than their height.

He became one of the more intimidating shot-blocking presences in the league. By January 1987, McHale was reputedly among the five most complete players in the world. That season, he averaged 26.1 points (on 60.4% shooting) and 10 rebounds. Offensively, he was arguably as virile as that first-time scoring champ in Chicago, the guy with the bald head and the shoes.

But as good as McHale was, there was Bird, and Magic--and the guy with the bald head and the shoes. McHale, incredibly talented and amazingly affable, resigned himself to the fact that his career would be played largely in the shadows.

*

It was sometime around the apex of his career when the family financial adviser informed the McHales they were set for life, a fact that prompted McHale to say, “Other than buying the lake house (in Minnesota), I do basically the same things now, except with better stuff.

“I don’t think of myself as doing anything that’s all that important. I just love to play basketball. How great is life? You got everything you need. What else do you need? I laugh every time I go to work.”

A broken foot cut considerably into his professional mirth. On March 11, 1987, in a game against the Suns, Larry Nance and McHale crossed feet and McHale heard something snap.

From the moment McHale fractured his right foot, his game would never be the same. In the weeks to come, McHale sprained both ankles, yet plodded on, through the 1987 playoffs. Although he continued to average more than 20 points the next three seasons, they were seasons marked by surgeries rather than triumphs. Perhaps not coincidentally, the Celtics haven’t won a championship since.

Parish aged. Bird hurt his back, tried to play, then retired after he won a gold medal in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. McHale, who had sworn he would never again subject his body to searing pain, did just that. By October 1992, McHale couldn’t bear the thought of another training camp.

“I had told my wife and my kids that I was done playing,” McHale said. “I was hurt at the time, my ankle was bothering me. But then the kids started bugging me, especially my two boys. They wanted me to play, they loved the other guys and they wanted to be ball boys. So I geared it up one more time for Mike and Joe.”

For Mike and Joe, McHale suffered through the worst regular season of his career. After adding back pain to ankle pain, he had just one more burst of greatness left, and he saved it for the playoffs. In the Celtics’ first-round loss to the Charlotte Hornets, McHale averaged 19 points, 7.3 rebounds and 1.75 blocks. In his very last match, a gut-wrenching, one-point loss in a thrilling Game 4, McHale nearly pulled off one more miracle -- but his last-second, alley-oop pass to Dee Brown was tipped away at the buzzer.

“It’s kind of amazing,” McHale said, “that my career ended on a pass.”

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.