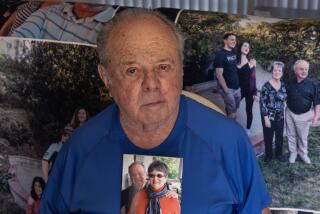

Death Hits Painfully Close to Home Again for Mickey Mantle

- Share via

Death was always so close to Mickey Mantle’s consciousness that they became joking companions. But Mantle was always laughing at himself.

“If I’d have known I was going to live so long, I’d have taken better care of myself,” he said when he reached 60. It was his way of kidding the late-night mileage he’d burned off that marvelously imperfect body.

No male Mantle that he knew had lived past 40. He could deal with his own mortality. Losing a son is another kind of tragedy. Children are supposed to outlive their parents.

Billy Mantle, 36, died Saturday after collapsing at a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center near Dallas. The cause of death was a heart attack, a condition apparently worsened by Hodgkin’s disease, according to Roy True, a close friend and Mantle’s lawyer. Billy had Hodgkin’s since he was 19. He’d had a heart problem for two or three years.

Unlike Mantle’s other three sons, Billy was seldom involved in his father’s businesses. He’d work on occasion at the fantasy camp Mantle and Whitey Ford ran together for a time. Billy didn’t care to work on the field.

The best of times were in spring training when the families of the players often would be in the same hotel. Joan and Whitey Ford walked in Fort Lauderdale Tuesday and remembered. “The Rizzutos would be on the second floor and the Mantles on the fourth and we’d be on the ground floor,” Whitey Ford recalled wistfully. “Joan would always have the tub full of hot water because the kids would come out of the ocean frozen. At any time there would be two Mantles, two Fords and a Rizzuto in the tub.

“They thought they were going to lose Billy a while ago. Then he got better; it’s hard to figure. I think of all the years and good times.”

Hodgkin’s was in Mickey’s family. And his father, Mutt Mantle--the man who named him Mickey after the great catcher Mickey Cochrane and the man who made him a switch hitter--left him with a pattern for living. “So what the hell,” Mutt said. “Live while you can.” And Mickey did.

That first season with the Yankees, Mantle tore up a knee in the 1951 World Series. Mutt took Mickey to be examined at Lenox Hill Hospital. Getting out of the taxi, Mickey placed his hand for support on the shoulder of his father, who had played ball with him, who had swung the sledge beside him in the lead mines near Commerce, Okla. Mutt Mantle collapsed from the weight, his spine already ravaged by Hodgkin’s disease.

It was the first Mickey knew of his father’s condition. He’d known of his family’s medical history since he was a child. He wrote in his 1985 autobiography “The Mick” with Herb Gluck:

“In 1944 with me in ninth grade, Grandpa Charlie got very sick. He had Hodgkin’s disease, a form of cancer that attacks the lymph nodes and eventually penetrates bone marrow.

” . . . I didn’t understand death and sickness very well. . . . It just seemed that all my relatives were dying around me. First my Uncle Tunney, the tough one, then my Uncle Emmett. Within a few years--before I was 13--they had died of the same disease . . .

“I never forgot that moment, standing beside the casket with my little twin brothers Ray and Roy, the three of us looking down on him and my father whispering, ‘Say goodbye to Grandpa.’ ”

Mickey was playing football at Commerce High when he was kicked in the left shin, and by the next morning his ankle was grotesquely swollen and he had a fever of 104. Doctors talked for a time of amputation before penicillin controlled the condition. But there was another scar in his mind.

In 1951 at Lenox Hill they put Mickey and his father in the same hospital room. They watched the rest of the World Series on television. Mantle wrote of the doctor knocking at their door: “It’s . . . well, it’s Hodgkin’s disease, I’m afraid there’s not much we can do. . . . You can take him home. Let him go back to work or whatever he wants. I’m sorry, Mick.”

The next spring Mutt Mantle was gone. “What had happened to him in the 39 years of his life, with all the scrambling and disappointments and frustrations?” Mantle asked in print 33 years later. “Where did it get him?”

So Mickey Mantle lived his own life to his father’s bit of advice. Mickey laughed at himself and his drinking. He had such a good time. And he was great. One time he came off the disabled list a day earlier than he expected and was called on to pinch hit through the gray haze of his hangover. And he hit a home run. “Boys,” he said, “you’ll never know how hard that was.”

It was just last month that Mantle realized there were whole segments of his career, of his life, that were lost in that gray haze. He admitted himself to the Betty Ford Clinic to try to fight the grip of 43 years of hard drinking.

He had been out two weeks when Billy Mantle, the third of his four sons, the one named for Billy Martin, collapsed after leaving the cafeteria at the Intervention Judicial Treatment Center near Dallas.

In later years Mantle lamented the time he didn’t spend with his sons. They had spring training and usually wouldn’t be together again until the end of the World Series. The boys had lives of their own in Dallas, and Mickey didn’t have the All-Star break as a vacation.

“Then, at 19, something else happened,” Mantle wrote. “A small lump developed behind (Billy’s) ear. . . . It turned out to be Hodgkin’s disease, the same disease. . . . “I often wondered why the disease had skipped me. . . . I had been expecting it all my life. For that matter, why had it spared my brothers, my sister, and their children? Why had it picked Billy?”

Billy’s spleen was removed. The disease slowed. Five years later the cancer had spread and he was given a 25% chance of survival. “Then Billy went into remission,” Mantle wrote. “A miracle.”

He’d been in remission since 1989.

Mickey Mantle used to say he’d never live to collect his baseball pension. He was the first Mantle he knew to live past 40. He’s 62.

“I haven’t tried to call him yet,” Ford said. “Let him have this time. I’ll wait a day or two. I’ll call.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.