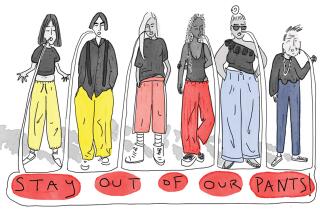

POINT OF VIEW / BOB OATES : The Baggy ‘90s : Today’s Basketball Uniforms Are Two Sizes Too Big; Though High Fashion, They Lack a Sense of Style

- Share via

You hear it said in front of many television sets: The worst thing about basketball players today is their baggy uniforms.

Sartorially, theirs is a world in which taut and trim have been abandoned as they proved during the NCAA tournament again this spring.

In the judgment of their critics, the athletes have created a kind of fashion--basketball baggy--that lacks a sense of style.

Indeed, the nation’s basketball players--college and pro alike, women as well as men--are making a fashion statement that can be termed a sweeping denial of style.

National reaction, predictably, has been divergent:

* An Establishment perception: Taste is out. Baggy’s in, and that isn’t all. Grunge is in, too. It’s a big-city, teens-and-20s look: blacks, whites, Latinos. You see it at all the games, the parties, the restaurants. Nobody cares how they look anymore.

* A counterculture reply: They look like this because they do care how they look. They work at being sloppy. Rejecting middle America--which they consider a closed society--they reject, in the process, established notions of aesthetic appearance. And, in staking out their own territory, street kids and basketball heroes alike use their clothes as a form of protest.

It isn’t the first time that’s happened. Those who feel oppressed often do odd things in protest movements.

For example, a white group protesting what it considered unfair taxation put on Indian clothes and war paint 200 years ago and dumped British tea into Boston Harbor.

A difference on today’s basketball courts is that the players aren’t protesting that hard. What’s more, in any balanced view, the way they perform has to be more important than the way they look.

Yet in a civilized society, shouldn’t appearance count for something?

*

Many decent citizens today are making an art form of sloppy.

In basketball, most noticeably, that’s just what they think they’re doing.

“For 75 or 80 years, the three-inch

inseam was standard for basketball shorts,” Barney Wachtel, president of Russell Athletic Uniforms, said recently from Alexander City, Ala. “Then around (1990), the teams began asking for four inches, then six, then eight.

“Then in (1992) the University of Michigan called in an order for 10 inches. And it seems like almost every basketball player wants those floppy walking shorts now.”

Wachtel doesn’t presume to judge fashions.

“One of my rules is that I never rule anything out that I don’t like,” he said. “It’s all right with me if they want to play basketball in oversized (jerseys) and billowy shorts that are at least two sizes too big.”

So America has arrived at what some call the rejection era. On and off the court, a symbol of the times is the oversized, dress-down look.

In the stores, some costly, fashionable garments resemble the rumpled ensembles that have been in the attic since Grandma wore them to hard-times parties in the ‘30s.

The country is in a coarsening mode that probably began on the streets, where, according to New York Times Fashion Director Claudia Payne, clothes designers get most of their ideas.

“Fashion trends have a way of moving off the streets and the rock stage to the runways,” Payne said.

And on to the gymnasiums and arenas, where, in the estimation of many viewers, basketball baggy is more fashion than style.

A dictionary difference?

Fashion: “A way of dressing or behaving that conforms to a prevailing, often short-lived custom, use, or mode.”

Style: “Good or approved fashion conveying a quality that gives distinctive excellence to forms of behavior or attire.”

Such usage is inevitably subjective. But any way you cut it, the absent element in the baggy ‘90s--nationwide--is an enlightened sense of style.

The dividing line could be that pair of handsomely tailored new jeans over there--the expensive pants that the manufacturer has deliberately ripped in both knees.

Distinctively excellent? Not quite.

*

To the surprise of few, a fashion-world consensus on the baggy ‘90s hasn’t yet developed.

Although Vogue magazine writers have persuasively condemned the look, many journalists are neutral--at least on baggy sports gear. And Los Angeles Times Fashion Editor Mary Rourke has been supportive.

“I happen to like (today’s) basketball uniforms,” she said. “It seems to me that they’re closer to the real personalities of the players.”

Still, Rourke sides with other experts on one thing.

“(Baggy) is a fad,” she said. “It will be out of fashion any minute.”

From her New York Times office, Payne agreed.

“The joy of fashion is variety,” she said. “The baggy look won’t last.”

In basketball, though, it could be around awhile because 1990s players are so obviously in tune.

And, uniquely, they alone--in the history of uniform wearers--have been able to control the destiny of their uniforms.

In the military, in law enforcement, and most particularly in other sports, those who wear uniforms have traditionally had no say in their design.

Michael Jordan was the pioneer who changed all that, introducing baggy into sports--perhaps inadvertently. In his days with the Chicago Bulls, wearing his North Carolina shorts under his NBA uniform as a demonstration of college loyalty, Jordan had to make room for them.

“I also think he was seeking another way to be different,” said Amateur Athletic Foundation official Skip Stolley. “The one-piece uniform is next. In a couple of years, almost every male and female athlete in track and field will be in a one-piece suit.”

Jordan, continuing as a clothes designer, might even bring the one-piece look to the NBA, where his former coach, Phil Jackson, had no objection the first time.

A laid-back intellectual, Jackson--quite the opposite of Bob Knight--could see that Jordan’s appearance didn’t really matter.

Michigan took the long, long look into college ball for similar reasons.

“When Steve Fisher succeeded Bill Frieder (as basketball coach), he wanted a changed look,” said Michigan equipment manager Bob Bland.

Unhappily for connoisseurs of the sleek and svelte, he got it.

*

The sports uniform is comparatively new in athletics. For centuries, athletes competed in the nude. Even after uniform apparel had been designed for sailors, soldiers and policemen, team games were played in street clothes for years.

When sports entrepreneurs got around to it, however, their reasoning matched Napoleon’s: Uniform clothing promotes pride in belonging as well as confidence in performing and a strong sense of unity with the group.

The uniform itself is thus a weapon in the Marines, or basketball, or any other team sport.

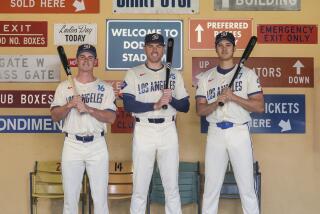

A guest in any major league locker room before any game confronts the reality: The players, as they draw on their uniforms, undergo a transformation. One minute they are chattering youngsters, indistinguishable from any other bunch their age. An instant later, in the uniforms they have coveted since boyhood, standing taller, filled with major league pride, they are skilled combatants who are more athletically gifted than any other young group on earth.

Or so they feel.

That’s what Hall of Famer Warren Spahn meant when, describing what he misses most about major league baseball, he said: “Just putting on the uniform.”

On many basketball, baseball and football teams, that attitude in recent years has begun to clash with one that is wholly different but equally powerful. The players, as much as they value team membership, also wish to express their individuality.

“There are a lot more me-first guys today,” veteran NFL defensive star Ronnie Lott said. “Carried too far, it can devastate a team.”

But it hasn’t happened yet, Lott said, noting that the Chicago Bears won the Super Bowl with a quarterback who, briefly, wore an advertisement on his headband.

That was Jim McMahon, who was disciplined, sort of, by Commissioner Pete Rozelle.

In the NFL, the most military of sports, the present commissioner, Paul Tagliabue, stamps out individuality by fining players who, for example, intentionally wear sagging socks.

“If we don’t stop that at the start, the (individualists) will take over,” Tagliabue said.

In women’s sports, following the NBA’s lead, they have taken over. Female athletes today wear three kinds of shorts--baggy, high-cuts and traditional.

And despite the drastic differences in their three fashions, they give the same two reasons for wearing each: They’re more comfortable, and they enhance performance.

Basketball players, the ultimate team-playing individualists, also plead comfort and performance when asked about their baggies.

All such arguments tend to be less than persuasive. For years, athletic equipment engineers have required that the uniform move with the body. Baggy lags. If it doesn’t retard performance, it is at least out of sync with the motion of the body.

The real explanation for any popular look--sports or otherwise--is almost certainly the same in all instances: adherence to perceived high fashion.

And in the baggy ‘90s, most of the time, you know what that is.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.