‘90s FAMILY : Fractured Fables : All’s perfect in fairy-tale land, right? Not always. Jon Scieszka proves kids (and adults) also love the dark, dismal.

- Share via

BOSTON — Oh sure, dis the Three Little Pigs.

Why not pick on the Ugly Duckling? Why not create a story where the duck doesn’t grow up to be a beautiful swan--just grows into a really ugly duck? How about fixing Cinderella up with Rumpelstiltskin? They could be Cinderumpelstiltskin, and when the beautiful princess kissed the frog, he wouldn’t turn into a handsome prince. He’d stay a frog.

These scenarios bring a gigantic smile to Jon Scieszka. And well they should, since they are contained in his ragingly iconoclastic storybooks, “The True Story of the Three Little Pigs” (Viking Penguin, 1989) and “The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales” (Viking Penguin, 1992).

With their wacky, highly irreverent renditions of coveted fairy tales, Scieszka and his illustrator, Lane Smith, have waged a frontal assault on conventional children’s literature. To date, “The True Story of the Three Little Pigs” has sold 730,000 hardcover copies. Signed first editions sell for $100 to $200 a copy.

To the occasional embarrassment of the author and illustrator, the books also get respect. “The Stinky Cheese Man” won the 1992 Caldecott Award, one of children’s literature’s most prestigious prizes, as well as an Abby Award, conferred by American Bookseller magazine. In an essay titled “Deconstruction and Self-Reference in ‘The Stinky Cheese Man,’ ” an academic journal offered plaudits the author and illustrator found incomprehensible.

On some college campuses, books by Scieszka and Smith have acquired cult status. Last year, a Vassar College student wrote to Viking Penguin to report that a group of seniors had gone outside and read “The True Story of the Three Little Pigs” out loud to mark the official end of childhood.

But Scieszka, 40, has no intention of giving up his status as an honorary kid. He has Lyle Lovett hair, olive-green eyes and a wicked sense of whimsy that must have sent his teachers running for cover. On a swing through New England, Scieszka talked about the crossover appeal of books aimed at his favorite people in the world--second-graders.

“I don’t think I ever expected it,” he said, marveling at the volume of letters that have come to him from high school and college students.

The dark verbal and visual humor of Scieszka and Smith seems to have hit a nerve with Generation X--and equally with the grade-school students for whom it was intended. Smith cites Halloween as his favorite holiday, and describes Maurice Sendak, Arthur Rackham and Edward Lear as his artistic inspirations. Scieszka, for his part, used Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” as a textbook when he taught second grade.

“They loved it,” he said. “You’d tell them about this guy who turns into a cockroach, and they’d go, ‘No way, man, no way.’ ”

He drew the line at Kafka’s “Penal Colony,” explaining, “I thought it might be a little harsh.”

But had he tossed that tale at them, Scieszka believes, the kids probably would have gotten it. “Kids are way underestimated,” he said. “People definitely don’t give kids credit for how smart they are. And we don’t give them enough ways for them to show how smart they are.”

Scieszka reached these conclusions after several false professional starts. He studied premed in college, all the while scribbling “tortured adult fiction.” Realizing one day that he would probably be miserable as a doctor, he switched to creative writing in graduate school at Columbia. To support himself and his family, he painted apartments. “Some of my finest works were closets,” he boasted.

Later, he taught in a Manhattan private school. Still hammering away at his deep and dreary adult prose, Scieszka decided that maybe grown-ups were not his true constituency. In children, he found “the same smart people I had been trying to reach. They were just a little shorter.”

His graduate school professors flogged him with the importance of “suspending disbelief,” a hard nut for many pragmatic adults to swallow. But children “live in that world,” Scieszka said. “Their disbelief is already suspended. That’s what makes them such great critics.”

A lawyer offered Scieszka rent-free writing space in his firm in exchange for painting his apartment. So every day, Scieszka would go to the office dressed in his lawyer’s costume, a suit and tie. While the professionals around him drafted legal briefs, Scieszka wrote about pigs and ducks.

His decade of failed writing for grown-ups turned out to have been an apprenticeship for Scieszka, as did his lifelong fascination with myths and fairy tales from around the world. All good fiction relied on a single element, he decided: “A well-told story. That’s the secret.”

Scieszka and Smith also draw heavily on the ages-old oral tradition of storytelling, “which is alive and well in kids’ books,” Scieszka said. They also avoid preaching to their young readers, or shoving social significance at them. “I was taught by kids not to be some sort of didactic, moralizing person,” he said.

But sometimes grown-ups still long for profundity. At a signing recently, an earnest adult asked Scieszka to inscribe “The True Story of the Three Little Pigs” with something meaningful: “You know, like, ‘There are two sides to every story.’ ”

Scieszka tried not to gag. He wrote quickly, hoping that the grown-up wouldn’t look inside the book until he got home. What he wrote was, “There are two pigs to every story.”

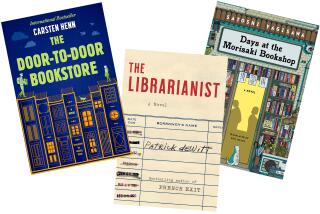

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.