It’s Arbitration That Has Owners Seeing Red

- Share via

Now that the obligatory opening ceremonies are finished and Dollar-A-Defeat Night, Bring Your Own Toilet Paper Night and Boycott The Brewers Night are behind us, it is finally time to play ball.

Time to salary arbitrate--the real game the owners were attempting to lock out during the past autumn, winter and spring.

Here are a few reasons why:

* Alex Fernandez, a Chicago White Sox pitcher with an 11-7 record and a 3.86 earned-run average last season, has filed an arbitration figure of $3.9 million for 1995--up from $758,334 in 1994.

* Andy Benes, a San Diego Padre pitcher with a 6-14 record and a 3.86 ERA, is requesting $4.4 million--up from $3 million last year.

* Rick Wilkins, a .227-hitting catcher for the Chicago Cubs, is asking for $1.7 million--which would nearly quintuple his 1994 salary of $350,000.

* Scott Erickson, 8-11 for the Minnesota Twins last season with an ERA of 5.44, is looking for, no, not another line of work, but a raise of $775,000--lifting his salary from $1.325 million to $2.1 million.

However, as his agent will soon remind an impartial third party overseeing these proceedings, Erickson did have a no-hitter last season.

And, seven bonus victories after that.

And, a lower ERA than the Minnesota staff average of 5.68.

What do you want from him?

Blood?

The salary cap alone didn’t topple and destroy the World Series. Revenue sharing wasn’t what prevented Matt Williams from affixing his name to the top of the all-time single-season home run chart, right above Roger Maris’.

Arbitration was the smoking gun in both cases. The owners loathe arbitration, despise arbitration. How intense is the hatred? Enough to shut down the last 1 1/2 months of the season and absorb a $124-million hit in operating losses, according to figures recently released by Financial World magazine.

The owners gripe about free agency, but arbitration is the true bane of their financial world. In the free-agent system, the owners maintain one element of control. It is called restraint. But arbitration is largely a game of chance and certainly a game of chicken--with no middle ground, only ticker tape for the winner and tourniquets for the loser. Hose off the table and send in the next case.

Rather than allow a mediator to split the difference, baseball arbitration has always been an either/or proposition. Either Kevin Tapani gets what he wants (he just filed for $4.2 million) or the Twins get to pay Tapani what they want ($3 million). There will be no compromise at $3.6 million.

So, unless a settlement is reached outside chambers, Yankee pitcher Scott Kamieniecki (8-6 in ‘94) will make either $1.475 million . . . or $890,000.

And Padre shortstop Andujar Cedeno (.263) will make either $1.5 million . . . or $850,000.

And Oriole third baseman Leo Gomez (.274) will make either $1.85 million . . . or $925,000.

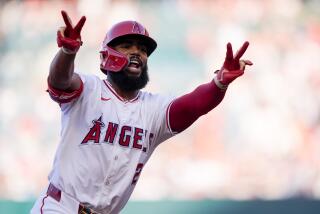

Then there’s Chili Davis’ kamikaze approach. Still steaming over the Angels reneging on last winter’s three-year, $11.25-million contract offer, Chili has decided to vent a good deal of it in the arbitration process. Chili filed at a whopping $5.1 million--the highest figure to be submitted Friday--and now waits to see if an arbiter will bite on it.

Chili can argue statistics; he led the Angels in batting average (.311), home runs (26) and RBIs (84). Those are not necessarily $5.1-million numbers, but Chili can also argue integrity-in-negotiations and raise the question: How did a “firm offer” extended during the middle of a players’ strike--with no baseball on the horizon--suddenly slink off the table once real games, and real paychecks, became imminent?

Chili filed high to hit back at the Angels. If he is able to persuade an arbiter, he will hit the Angels where it hurts them the most.

If not, he parachutes onto a $4.3-million landing, having prodded the club into filing a figure $1.5 million higher than his 1994 salary.

At 35, in his 14th season, Chili is one wizened veteran.

What baseball should do is remove arbitration from salary-setting process and apply it to areas that truly need it:

Commissioner: Fay Vincent . . . or Bud Selig.

Playoffs: Three tiers . . . or no tiers, just like last year.

World Series: First pitch at 1:05 p.m. . . . or final out at 1:05 a.m.

American League West: Permitted to play . . . or replaced by the Pacific Coast League.

Pitching in St. Louis: Ken Hill . . . or Chris Miller.

Winning promotions in Anaheim: Buck baseball . . . or Buck Rodgers.

Hero for the ‘90s: Ken Griffey Jr. . . . or Barry Bonds.

Rotisserie leagues: Banned . . . or kept under safe quarantine.

National pastime: Football . . . or basketball.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.