For CSUF Baseball, Coach is Diamond in the Rough : Sports: Augie Garrido’s painstaking methodology has brought honors to a college unused to athletic excellence.

- Share via

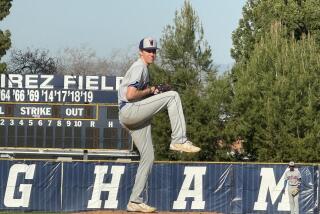

FULLERTON — Augie Garrido is in one of his favorite haunts, behind a batting cage working with one of his players at a midweek practice.

D. C. Olsen is on one knee, his right leg stretched stiffly to his side. It seems a strange pose for a first baseman who is 6 feet and 215 pounds.

A teammate tosses baseballs softly from a few feet away, and Olsen swings, first with his left arm, then his right, and finally with both hands gripping the bat.

Garrido offers a suggestion here, some praise there, reinforcing and reminding. The drill is one of many that are fundamental to Garrido’s approach to coaching baseball at Cal State Fullerton.

“This is really what I like the most, helping the players develop,” Garrido says.

His methods, formed by what Garrido calls his “teacher’s mentality,” have produced extraordinary results at a university not accustomed to athletic excellence.

In two stays at Fullerton, Garrido has won two national, six NCAA regional and 15 conference championships. This season, his 20th at Fullerton, the Titans are ranked No. 1 in the nation with a 49-9 record and are trying to earn Garrido his seventh trip to the College World Series.

“There’s a hidden part of Augie that not many people know much about . . . how much he demands of himself as a teacher of the game,” said Florida State Coach Mike Martin, a longtime friend and rival. “He’s genuinely concerned about bringing everything out of a person he can.”

Few college baseball coaches have been more successful. Garrido’s teams at Fullerton, San Francisco State, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and Illinois have won 1,099 games. Only 11 NCAA Division I coaches, six still active, have won more than 1,000.

“I remember when I first met him at the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita [Kan.] in 1977,” Martin said. “There was a player on the team that left, went home. Augie shouldered all the blame himself and said he felt responsible because he didn’t make him a much better player than he was. It made such an impression on me.”

Garrido, 56, is not the rambunctious coach who arrived at Fullerton in 1973. And he’s not as brash as when he stepped in front of the microphones after his team lost its first game in the 1979 College World Series and predicted it still would win the championship. After all, it was double-elimination, right? A week later, the Titans did as Garrido had predicted.

“He was more emotional in those earlier days,” said George Horton, who played for Garrido in 1975 and 1976 and has been his associate head coach the past five years. “It probably was a more win-at-all-costs philosophy then. My way or the highway, you know? I think he’s changed as the players have changed.”

Garrido’s face is more lined now, his hair gray. His disposition has become more mellow, more composed.

He still likes to swing the bat with his players occasionally, although he might be more cautious in the future. A few weeks ago, Garrido ruptured his right Achilles’ tendon hitting ground balls. He had to have surgery, but it took him away from the team only a few days.

Garrido says he has matured.

“ Defiant , that’s probably a good word to describe the way I used to be,” he said, smiling. “My father always used to laugh and say, ‘Augie, you could never have played for you.’

“But most of what I’ve learned, I think, has been because I’ve been willing to try almost anything I thought was right.”

Garrido grew up in the housing projects of Vallejo in Northern California. His father, a fast-pitch softball catcher, worked at the shipyards in the day and the neighborhood recreation center at night. Garrido went to the center with him and became involved in sports there.

Garrido defied his father by refusing to work at the shipyards after graduating from high school.

“I remember at that time seeing a guy on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ who was really good with a yo-yo,” Garrido said. “I decided that if you’re really good at anything, even doing the yo-yo, you can make a living out of it, so I told my dad, ‘I’m going to college.’ I told him the one thing I knew was sports, and I’d gotten a lot of that from him. I wanted to be a coach.”

Garrido went to Fresno State, lived in a migrant worker shack in an almond orchard and played baseball. He spent six years in the Cleveland Indians’ minor league system as an infielder, then started coaching at Sierra High School in Tollhouse, Calif.

After three years there, a year at San Francisco State and three at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Garrido arrived at Fullerton. Neale Stoner, basketball coach at San Luis Obispo when Garrido was there, had become Fullerton’s athletic director; he hired Garrido less than a year later.

“I probably wouldn’t have moved at that point if it weren’t for Neale and the president at the time, Don Shields,” Garrido said. “I felt real good about their commitment to the program.”

In the eight years before Garrido arrived, Fullerton had won 35% of its baseball games. That changed quickly. The Titans, then a Division II baseball program, won the conference championship in Garrido’s second year. Soon after, Stoner told Garrido he had good news and bad news.

“He said the good news is that we’re increasing your budget by $4,500,” Garrido said. “But the bad news, he said, is that we’re going to Division I with that budget, which still was only about $6,000.”

Garrido learned to make the most of less, even if the move to the NCAA’s highest division put the Titans against tougher competition, schools with rich sports traditions. In 1975, the Titans won the Pacific Coast Conference championship and advanced to their first NCAA Division I regional playoff. It was a quick move up in class: The regional was at USC, which had been dominating college baseball under Rod Dedeaux.

“I remember at the coaches’ get-together the night before, the organist came up to me and asked if she could have a copy of the music for our fight song,” Garrido said. “I remember saying, ‘I don’t think we have a fight song. I’m not sure we even have a band. But the players kind of like a song by the Doobie Brothers.’ ”

Instead, Garrido recalls, the organist played “It’s a Small World” when the Titans were introduced, and some rival fans jeered the team as “Cal State Disneyland.”

But upstart Fullerton stunned USC in the opener, and the Titans went on to win the championship from Pepperdine on a home run by Horton.

“I really think the spirit for our program was set by that, even though we were eliminated quickly in the College World Series that year,” Garrido said. “But just being in Omaha [Neb., the series site] was a big thing.

“It introduced me to the type of athletes out there, the type of athletes you need to win on the Division I level. But it also helped us get them.”

Garrido says Fullerton’s location was a vital factor in its success.

“I knew if we were going to continue to be successful, we had to get the good players here,” he said. “We didn’t have the money to go all over recruiting them, but if we were in the oil industry, we were sitting in the middle of the oil. The area was the best resource we had.”

In 1975, several players from Cerritos College became the building blocks, among them pitcher Dan Boone, who won 24 games in two seasons and was the first Titan player to reach the major leagues, with the Angels.

All 34 players on this season’s roster are from California, all but 12 from Southern California. Eight are from Orange County.

Garrido says the first national title in 1979 was another big leap forward. After the opening-game loss, the Titans battled through the consolation bracket and defeated Arkansas, 2-1, in the title game, fulfilling Garrido’s prediction.

“I just felt going in that we had the best players in the tournament,” Garrido said. “But now it was a matter of doing it, not just talking about it.”

Fullerton won another regional contest in 1982 and the College World Series again in 1984. That championship is memorable to Garrido because he believed the players overachieved.

“That team gave me a clear definition of what the word champion really means,” he said. “It was a team that really rose to the occasion and was successful against all the odds.”

Stoner became athletic director at Illinois and lured Garrido there after the 1987 season with an offer of money and a pledge to build a successful baseball program in a conference where football and basketball were the reigning royalty. At the time, Garrido was having serious concerns about Fullerton’s commitment to baseball.

At a school that hadn’t won a Big Ten baseball championship in 26 years, Garrido won two in three years. But then Stoner resigned under fire and was replaced as athletic director by football Coach John Mackovic. Baseball again became less of a priority.

The decision by Larry Cochell, Garrido’s successor at Fullerton, to leave for Oklahoma couldn’t have come at a better time for Garrido, who saw new hope when the university committed to building a new baseball field. Fullerton had to play two more seasons at antiquated Amerige Park during construction, but it was as though Garrido had never been away.

The 1991 team won the conference title, and by 1992, the Titans were again in the College World Series, where they lost the championship game to Pepperdine.

Players who played for Cochell and Garrido at Fullerton noticed the difference, even though Cochell’s teams also were successful.

“Augie was much more aggressive, and he put a lot more emphasis on winning,” said Phil Nevin, 1992 college baseball player of the year. “I like hard-nosed guys like that, and I think it was better for me. I liked his brand of baseball.”

A year ago, the Titans won another regional championship at Stillwater, Okla., with a dramatic, extra-inning victory over Oklahoma State. The Titans advanced to Omaha and reached the semifinals before losing to Georgia Tech.

But things still are not the way Garrido would like them to be.

Fullerton’s stadium is incomplete because of a lack of funding. There are no permanent restrooms, no team meeting room, no offices for the coaches. There is no regular maintenance crew working for the playing field, which was shabby most of this season.

Garrido said the improvements haven’t come as fast as he hoped when he returned, but he remains optimistic that they will. At this stage, they have become even more important to him.

Fullerton’s stadium has never been up to the standards of a regional tournament site, which means the Titans must fight for World Series berths on the road. This year, they travel to Baton Rouge, La., where they’ll open play Thursday in a regional that includes powerful host school Louisiana State.

Somehow Garrido has turned a disadvantage into an advantage by building a road-warrior mentality among his players.

“Nobody prepares a team to play on the road better than Augie does,” said Florida State’s Martin. “That’s got to be motivation. And he’s probably the most difficult coach to prepare for anyway, because you never know what his teams are going to do.”

On the field, Garrido’s teams always seem to make the most of any glimmer of opportunity. Timely bunts, an unexpected steal, a well-executed hit-and-run are all part of the pressure Fullerton applies to rival defenses, inning after inning.

“I remember in 1984, we had a real good club, and we got three runs up on them, and I never in my life saw people bunt the ball as well as they did,” Martin said. “They beat us, 5-3. They drove me crazy. Another time, he came to our place and they stole third base on us three times. I couldn’t believe it.”

Twenty-one Fullerton players have played in the major leagues; six have been first-round picks. Nevin was the first player chosen in the 1992 amateur draft and appears on the verge of reaching the majors with the Houston Astros. Tim Wallach of the Dodgers also was chosen college baseball player of the year, in 1979.

Four of Garrido’s assistants have gone on to Division I head coaching jobs, including Dave Snow, who has built a strong program at Long Beach State. Horton was offered the Washington State job last year but turned it down to remain at Fullerton.

Snow, whose teams battle Garrido’s regularly in the Big West Conference, leaves no doubt about Garrido’s influence on him.

“It’s that gift he has . . . that ability to motivate,” Snow said. “It inspires others. As a coach, he has that intensity . . . the focus. To him, there aren’t any little things. Everything is important.”

Garrido relies heavily on his assistants, but Horton says the program clearly revolves around Garrido.

“He is Cal State Fullerton baseball,” Horton said. “For him to be able to keep the program at the level he has through the years is really phenomenal, especially compared to the funding some of those other programs have.”

Tony Fetchel, who pitched from 1990 through 1994, points to the work ethic Garrido instills.

“As far as he’s concerned, it’s not a matter of being blessed with the most talent; it’s a matter of developing the talent you have,” Fetchel said. “And he teaches you a respect for the game. A lot of people don’t have that.”

After more than 40 years playing or coaching baseball, Garrido says what he respects most is the difficulty of playing it well.

He was in a whimsical mood not long ago, and he thought about that and said, “Did you see the movie ‘Backdraft’? Remember when the character Donald Sutherland played was trying to get to the essence of fire, and he very mysteriously said, ‘But have you seen the animal?’ And he got this sort of glow about him, like you knew he felt he had.

“Baseball is a lot like that. You know, ‘Have you seen the animal?’ Some people see it, and some people don’t.”

Garrido laughed, and there was a sort of glow about him.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Garrido’s Winning Ways

Augie Garrido’s Cal State Fullerton baseball team is ranked No. 1 in the nation with a 49-9 record. Throughout his career, Garrido’s teams have won about seven of every 10 games. His winning percentage: 1969 San Francisco State 1970-72 Cal Poly San Luis Obispo 1973-87 Cal State Fullerton 1988-90 Illinois 1991-95 Cal State Fullerton 1995: .845

***

PEER PRESSURE

Garrido is one of the most successful active coaches in Division I baseball. How he compares in career coaching victories: Coach/School Cliff Gustafson, Texas: 1,385 Al Ogletree, Texas-Pan American: 1,162 Jack Stallings, Georgia Southern: 1,128 Chuck Hartman, Virginia Tech: 1,103 Augie Garrido, Cal State Fullerton: 1,099 ***

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

* Named national Coach of the Year three times

* Won national championships in 1979 and 1984 at Fullerton

* Won two Big 10 titles in three seasons at Illinois

* Played in the 1959 College World Series with Fresno State

Source: Cal State Fullerton, individual colleges

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.