Worker Wrings Overcharges From Water Bills

- Share via

Bet you wish Timothy Marxer was your water meter reader.

When he goes out to check a meter, he ends up subtracting money from the water bill--not the other way around.

Marxer has created his own one-of-a-kind city job by prowling Los Angeles and looking for municipal parks, playing fields and lawns where drinking water is being used instead of irrigation water on grass and shrubs.

The water is the same, of course. But drinking water costs up to $3.99 per unit. A unit of water earmarked solely for lawn-sprinkling, on the other hand, is billed at a mere 62 cents.

When Marxer finds a golf fairway or flower garden being watered the expensive way, he makes officials change the meter billing to the proper, lower rate.

It sounds simple. But so far, the jovial 52-year-old has saved the city general fund $5.5 million that would have needlessly been paid to the quasi-independent Department of Water and Power.

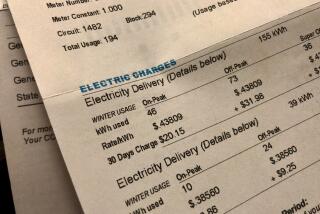

Municipal officials at first were incredulous to learn from Marxer that such huge sums of water money were going down the drain. But they say he has become so good at his water work that he’s going to be turned loose next on city electric meters and the DWP’s variety of power rates.

That brings a laugh from Marxer--who spends his evenings sitting on his living room couch, analyzing municipal water bills stacked on two TV trays in front of him. That frees him up to spend his days outside, poking through parkland bushes hunting for meters.

“I love doing this,” he said the other day as he chalked up another $36,559 in savings by locating a meter at a city-leased Sunland equestrian center that was sending drinking water into an irrigation line.

Officially, Marxer is classified by the city as a senior gardener--the job he held at the Department of Recreation and Parks when curiosity about water conservation regulations led him to start examining city water bills in 1990.

But he hasn’t pruned a rose bush or picked up a rake since earlier this year. That’s when municipal administrators asked the City Council to create a special investigator’s position for him.

At that time, Marxer had already saved $4 million in water charges for the parks department. He was itchy to check other city facilities’ meters as well.

Marxer remembers his bosses’ reaction when he made his first water bill discovery. It was a $503,000 overcharge on a meter located off Zoo Drive in Griffith Park where the DWP had mistaken slapped a drought conservation penalty charge on the bill.

“They first said, ‘C’mon, man who are you kidding?’ ” recalled Marxer. “Then my supervisor went with me to the DWP. He was stunned when he found it was true.”

Since then, Marxer’s water bill analyzing has discovered money needlessly flowing out of the city treasury in surges big and small:

* In Encino, he found that the huge city-owned Balboa Golf Course was being irrigated with drinking water billed at a rate wasting $842,873 a year.

* In South-Central Los Angeles, the cost of watering the rose garden at Exposition Park contained an unnecessary $33,000 a year in sanitation fees.

* Echo Park Lake was being filled at a drinking-water rate, wasting $331,000 a year.

Although the Department of Water and Power is a municipal agency, it bills its sister city departments for the water and power they use, just as a private utility would do.

But city officials say the need to closely watch water bills was not apparent in the past. That’s because the prices of drinking water and irrigation water were relatively similar until the late 1980s, when several years of drought led to conservation measures that include steep surcharges for excessive water use.

About the same time, sewer service fees tied to water usage were added to water bills by the city’s Sanitation Department. According to Marxer, $2.05 of the $3.99 cost of a unit (748 gallons) of drinking water goes to sewer charges. Irrigation water is exempt from sanitation charges since it flows into the ground, not the sewer system.

DWP administrators at the agency’s hilltop headquarters Downtown say they have gotten used to seeing Marxer march up to the special billing section’s governmental desk--with a smile on his face and a sheaf of water bills in his hand. Down the hill at City Hall, administrators say Marxer has already managed to cut the city’s $30-million yearly utilities budget by 25%.

City Councilman Joel Wachs agreed. He is a frequent DWP critic whose council Government Efficiency Committee pushed for Marxer’s unusual assignment with the Department of General Services. “I want to send him to check on power too,” Wachs said.

Although the DWP annually transfers 5% of its revenues to the city’s general fund--an amount expected to total $111 million this year--that is seen as payment in lieu of taxes, according to Wachs.

Wachs said he also is looking into ways that city law could be changed so employees such as Marxer could receive rewards--perhaps a percentage of the money they save. Despite the millions he has saved, all Marxer is currently eligible for is a city “productivity luncheon,” Wachs said.

Back in West Hills, Marxer shrugs off the thought of a reward. He is busily hunched over his TV trays. “I feel like Jean-Luc Picard standing on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise,” he says with a laugh. “ ‘What else is out there?’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.