An Eye for the Old : WHITE RABBIT,<i> By Kate Phillips (Houghton Mifflin: $19.95; 213 pp.)</i>

- Share via

It is the last day of an 88-year-old woman’s life. Odd flashes, scraps of phrases, brief blackouts and a piercing sadness come and go as, still sprightly, she tries to get through her daily routines. And, as is said of the drowning, her past life replays itself.

In “White Rabbit,” her first novel, Kate Phillips treats this not unfamiliar fictional situation in an unusual way. Ruth Caster Hubble’s recollections are not particularly interesting. Nor does the author tell them particularly well.

What holds us, though, is not Ruth’s 88-year history. It is 88-year-old Ruth herself, and her banal, comic and ferocious course through her last day. We do not especially care who the ancient swimmer may once have been, nor even that the breakers are about to submerge her. We care about and we are astonished at her scrawny and determined dog paddle.

When, as a novice police reporter, I saw a murder victim on a New York subway, for a few moments afterward there was no one in the weary, surly crowd on the platform who did not seem to be wearing a halo. They were alive. Ruth is formidably alive. The important thing about her deathbed, which she takes to only at the end of the day, is that it is her bed. Her outfits, carefully arranged in her closet, are her outfits. Her lunch sandwich is her sandwich, her afternoon walk is her walk and her annoyingly stubborn and distracted 88-year old husband, Henry, is her husband.

Our entry into the different country Ruth so magisterially inhabits takes place at 5:25 in the morning when, as usual, she wakes up in her bed or, rather, on it. Ruth sleeps in a sleeping bag spread atop the bed’s yellowed candlewick counterpane. That saves laundry, she calculates; a good part of “Rabbit” is taken up by Ruth’s grave and comic battle to maintain the calculations by which she keeps going.

There is the collection of carefully bagged scraps and greasy wrappers in her refrigerator. As rings mark a tree’s age, the contents of the refrigerator can mark a person’s. There is the elaborate ritual for setting out the garbage, the carefully drawn-up grocery list (one muffin, a small container of cole slaw--and four frozen turkey dinners because company is coming), which she will send out with Henry. He will get it almost right.

The flashbacks on that last day, some of them coming as fade-outs in the middle of a conversation, tell of a life whose disappointments become increasingly evident. There are repeated images of her first husband and one great love, Hale, and of Hale’s best friend, Frank, who courted her after Hale died and whom she turned down because she disliked his womanizing. Only bit by bit are other parts of the picture revealed. Her memory works like a print developing, with the darker parts showing last.

Hale, in fact, became fed up soon after they married and stayed away for months on business trips. The seductive Frank, on the other hand, may really have loved her; perhaps she should have taken a chance with him. Instead she settled in her mid-40s for the safe, well-to-do and utterly unappealing Henry and for a boring existence in a fenced, private-security community in Laguna Beach.

It is not an appealing portrait and the author, drawing it in terms of her character’s faint foolishness and soap-opera recollections, occasionally traps her writing in some of these same qualities. It is a flaw of tactics, not talent. The vitality, shrewdness and even a touch of nobility (along with the cantankerousness and fog patches) of Ruth in her old age are rendered subtly and sometimes thrillingly. Something has burnt away the foliage, leaving branches that are bare though gnarled with crotchets. Phillips has too much class to pronounce whether this is life triumphing or death approaching; there is no demarcation.

In any event, the print goes through another stage of development. After the dark that takes shape after the light, a different light takes shape. Henry, the geriatric clown--he keeps dropping his few remaining loose teeth into his dinner--gradually emerges differently. His infuriating tactical deafness provides safety for Ruth’s querulous manias; his feebly lustful passes are real love and keep her going through sheer irritation. He is a splendid character.

So is Ruth. She has been plaguing her granddaughter, Karen, with far-fetched warnings about Karen’s restless husband. There is a true instinct under the fog, though; Karen herself is uncertain. In two shrewd scenes that astonish without contrivance, Ruth finds the strength to comfort her granddaughter and to goad the husband into revealing both his fears and the decency that lies underneath.

As for death, it comes with a jauntiness that moves us without incurring the least twinge of sentimentality. Ruth receives no special wisdom, just a dim foresight. At the end of the day, she climbs onto--still not into--her bed. Cloudily, she seems to hear the telephone ring. It is the ghost voice of Hale, the first husband and misconstrued love of her life.

There are no marriages in heaven, not even bad ones. It is my private suspicion, though, that Henry may eventually worm his way in by the sheer tensile stubbornness of one or two of his loosening teeth.

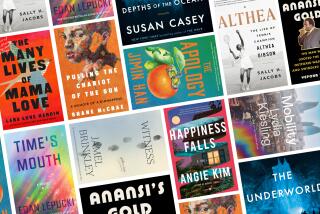

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.