Effort Targets Young Bosnian War Survivors

- Share via

Through a translator, Bill Saltzman heard the children’s stories of bombings and basements, shellings and snipers, land mines and lost years.

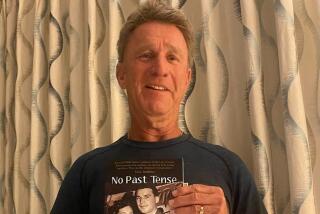

“They felt the war was just against them,” said Saltzman, a psychologist who traveled to the former Yugoslavia for seven weeks this summer as a consultant for UNICEF.

The war took a heavy toll on the children of the region and on people such as Saltzman’s translator, a 19-year-old former Muslim soldier named Amal.

“He felt responsible, because he hadn’t taken care of them,” Saltzman said.

Saltzman and UCLA professor Robert Pynoos arrived in Sarajevo in mid-June to lay plans for a postwar rehabilitation program for children. The program will be offered through local schools.

Pynoos, an expert in traumatic stress, stayed in the region for a week. Saltzman, a staff psychologist at the San Fernando Valley Child Guidance Clinic in Northridge, spent his time visiting Muslim and Serbian communities.

Amal drove Saltzman in an old Volkswagen to a bunker in the mountains where the young man once fought. Bobsleds had run past the site in the 1984 Winter Olympics.

The two talked about responsibility, about the possible and impossible, things at the heart of psychological troubles but often not talked about among Bosnian war survivors. “It was a very good day for both of us,” Saltzman said.

During his stay in Sarajevo, Saltzman had to bathe using buckets of cold water. He would jog to the outskirts of the city every morning, avoiding areas marked off as minefields.

“You can’t step off the asphalt anywhere in the country,” Saltzman said.

In a Serbian town, Saltzman’s hotel was rocked by a bomb blast at 3 a.m.

“I wasn’t that shook up,” he said. “I thought, either a major water main blew or we were bombed.”

But such experiences were barely a taste of what civilian life is like during--and after--war.

As stress builds, children may experience physical problems, stomach troubles, the return of bed-wetting, and difficulty sleeping, he said.

“When they hear cars backfire, the kids jump,” he said.

The war destroyed families, neighborhoods and the nation’s institutions, but it also robbed teenagers of critical developmental years. Instead of dating and socializing, they spent that time hiding in basements.

The youths reminded Saltzman of Los Angeles teenagers who have been traumatized by gang violence.

Saltzman, 41, traveled to the region even though he worried about his wife, who was four months pregnant. “It was a really rich experience,” Saltzman said of the trip.

Some of Saltzman’s experiences may be useful when the child-guidance clinic begins support groups for victims of violence and trauma.

UNICEF plans to eventually train school personnel to recognize children who need psychological help. Throughout the war the schools have served as a natural connection with children because they continued to meet with teachers, in spite of the danger.

“Those were the things that held people together,” Saltzman said.

And as Saltzman crossed boundaries created out of complex political situations and ethnic conflicts, he found a way to remain neutral. “One thing we can agree on,” he would tell his hosts, “is that the children need the help.”

Personal Best is a weekly profile of an ordinary person who does extraordinary things. Please send suggestions on prospective candidates to Personal Best, Los Angeles Times, 20000 Prairie St., Chatsworth, 91311. Or fax them to (818) 772-3338. Or e-mail them to valley@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.