Island Founder at Odds With Polygram Over Dueling Visions

- Share via

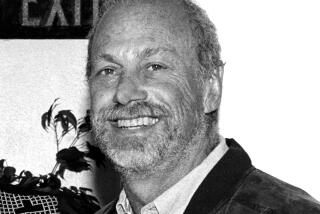

In a clash between one of the most successful music industry entrepreneurs and the world’s largest music company, Island Records founder Chris Blackwell sharply criticized the chairman of PolyGram and said he doubted he could accomplish his goals working inside the Dutch conglomerate.

Blackwell, whose cutting-edge company transformed such unknown acts as Bob Marley and U2 into international superstars, is so fed up with the corporate culture at PolyGram--which bought his music label eight years ago for $300 million--that he offered last week to resign from the firm’s board of directors.

Offering to quit the board, however, wasn’t exactly an act of protest. Blackwell’s move was prompted by a suggestion made two months earlier from PolyGram Chairman Alain Levy, with whom Blackwell has been at odds for more than a year, sources say.

“What I have come to realize is that it is not really possible for me to continue to grow creatively in the entertainment business within PolyGram,” Blackwell said in a phone interview from Oracabeza, Jamaica. “I feel that Alain Levy is restricting me and I don’t understand why. It is unlikely that I will be able to do what I want to do and still stay within the corporate structure.”

Competitors say Blackwell’s struggle with PolyGram reflects the problems entrepreneurs often have working within large corporate structures. But they also say it illustrates a larger problem facing the music industry.

The record business has gone through a dramatic transformation since the late 1980s when international conglomerates gobbled up a string of independent companies, buying out the music-savvy entrepreneurs who had built them and often installing their own business executives in hopes of pushing profits higher.

Blackwell and other entrepreneurs believe that meeting corporate demands for increased sales to drive up stock prices makes it extremely difficult to build careers for artists--the kind of cutting-edge acts that often don’t connect with the public until their second, third or even fourth album.

Blackwell, 60, who has run Island for more than three decades, is highly regarded in entertainment circles for his business instincts and commitment to artistic development. He built Island from a one-man operation into an industry powerhouse that introduced the world to ska and reggae music. Besides Marley and U2, his acts included Cat Stevens and Steve Winwood.

Over the years, Blackwell expanded Island into movies, resort hotels, animation and a line of independent cinema theaters. He is currently developing a company called Island Digital Media to develop DVD audio and video projects.

Blackwell’s offer to resign from the board raises questions about what role he will play in the future at PolyGram, which owns Island Films and is negotiating to finance and distribute Island Digital.

“When I renewed my contract a few years ago with PolyGram, I was under the impression that I was going to be able to build an entertainment business with an independent feeling within PolyGram,” said Blackwell, whose PolyGram contract runs out in 1999. “But it isn’t going to happen. I really believe that it is impossible for an independent type of company structure to work and grow within a corporation like PolyGram. You can’t sit and wait and do projections on everything the way they do. You have to trust the judgment of the people you hire. In my case, I feel that Alain has repeatedly disregarded my judgment.”

Levy declined comment, but a representative for PolyGram said Levy has always supported the artistic process and creative talent in the executives employed by PolyGram--including Blackwell. Sources at the company say Levy wants Blackwell to focus his attention on his expertise in music.

Island, whose U.S. market share is hovering at 1.5%, delivered a slow-selling album from U2 this year and has only two albums on the nation’s pop chart.

Top record executives often complain about corporate interference, but they typically do so privately--fearful that public outbursts would damage their careers. Sources say that Blackwell’s public statements are likely to infuriate Levy.

Growing tensions between the two executives erupted in August after Blackwell publicly criticized a decision by PolyGram’s film studio to edit “The Gingerbread Man,” an upcoming PolyGram film by Robert Altman--against the wishes of the veteran director. Blackwell sided with Altman, who threatened to remove his name from the film if PolyGram brought in another director to finish the movie.

PolyGram resolved the dispute amicably with Altman. But Levy felt Blackwell had shown disloyalty to the corporation and wrote him a letter on August 29 suggesting that he consider resigning from the board of directors. Last week, Blackwell wrote Levy a letter, in essence agreeing.

In an interview, Blackwell said he has grown increasingly frustrated at PolyGram since Levy rejected his proposals to acquire a chunk of Interscope Records and of alternative music cable station the Box.

After Levy chose to pass on the Interscope deal, Seagram picked up a half interest in the label for $200 million. Interscope has been the hottest label in the music business, generating revenues last year of nearly $300 million.

“Alain and I have not seen eye-to-eye for a long time,” Blackwell said. “I don’t understand Alain’s vision. He’s not a very communicative person. He never discusses anything with me--which is fine. But then just let me do my own thing. Don’t stop me at every turn.

“This is what the story really is: good and bad. Alain’s point of view is this: Just because I come up with these ideas, why should PolyGram automatically finance them? And he’s absolutely right. It doesn’t say in my deal that just because I have an idea PolyGram has to finance it. But I don’t think he has confidence in my judgment. And it’s very frustrating for me.”

PolyGram, a subsidiary of Holland’s Philips Electronics, is the leading record company in the world based primarily on relationships with strong indigenous talent in many countries.

But the company has had a rougher time in the U.S., where it controls only about 13% of the $12-billion market throughout the 1990s.

Over the last decade, PolyGram has invested more than $1 billion to acquire a handful of prominent U.S. labels, including Island, A&M;, Mercury, Motown and half of Def Jam. Some analysts say his vision helped transform PolyGram from a quiet classical music company into a major competitor in the pop world.

But PolyGram has suffered several setbacks, with executive shake-ups at A&M;, Mercury and most recently at Motown, where Andre Harrell was ousted after a costly unsuccessful two-year run. A&M; is in the process of rebuilding its black music department and Mercury Records has rebounded in recent months under new head Danny Goldberg.

Blackwell praised Levy for building the strongest music distribution network in the world and applauded Levy’s decision to hire Goldberg.

“[But] what corporations don’t understand is that you can’t run studies and projections on what is going to work and what isn’t in the entertainment business,” Blackwell said. “You have to decide if you want to be in business with a recording act or not. And what they don’t get is that entrepreneurs like me are more like acts than businessmen.

“Either you’d like to be in the Chris Blackwell business or not. Question things. Make suggestions--by all means. But don’t stop us at every single turn just because you don’t understand what we want to do. If Island Records was just starting out attached to a major corporation structure the way that label deals are set up now, we never would have survived. Not in this corporate environment. Absolutely not.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.