Requiem for a Heavyweight

- Share via

I was packing for a trip back to the West Coast when I caught the headline on a late-night radio program. It stopped me cold and forced me to sit down in my New York apartment. “Los Angeles’ longtime sheriff, Sherman Block, has died,” the announcer said with the same enthusiasm that he had given the weather report.

I was no longer listening. I was rummaging around my desk for the audiocassette I had planned to take with me on the plane. I had recorded the tape last summer at a kidney dialysis center in Encino in a meeting with a bespectacled, balding man who had already survived prostate cancer, lymphoma, a life at the heart of controversy and the simple wear and tear of being 74. When I arrived that August morning, Sherman Block was sitting in a low-slung recliner in an open room with other dialysis patients. He wore slacks and a short-sleeve shirt and was strapped to a machine that he visited three days a week, three hours a day. A television monitor faced him, and his business papers rested nearby.

As always, he replied to each query in a methodical, unhurried monotone. He was unruffled, until I voiced a question posed openly by many of his detractors and whispered by some of his supporters: Was he physically fit to continue the job he had held for nearly 17 years?

Bristling, the sheriff insisted that he indeed was healthy enough to serve another four-year term. Then he sank back into his chair and seemed to sink deeper into thought as we talked about his bouts with cancer, the subsequent surgery, his chemotherapy and his faltering kidney. “It certainly makes you aware of your own mortality,” he finally said. “And it causes you to realize that certainly no matter who you are, you’re not invincible.”

If there was anyone who appeared invincible in Los Angeles County politics and local law enforcement, it was Sherman Block. He had been with the department for 42 years. He had been sheriff since 1982. He had outlasted Los Angeles police chiefs named Gates and Williams and joked that he was now breaking in another one named Parks. And he told me how a neophyte politician named Richard Riordan had once approached him and asked, before announcing his own candidacy, whether Block was interested in becoming mayor.

At the end, the son of a milkman earned a sheriff’s salary that made him the nation’s highest-paid elected official. Not bad for a guy who once worked behind the counter of a Jewish delicatessen, who spent more time as a young deputy shooting rattlesnakes and chasing down speeders than seizing criminals on his Rolling Hills Estates beat, who busted Lenny Bruce for obscenity and then translated the comedian’s Yiddish vulgarisms on the witness stand, who wore Ray Milland’s salt-and-pepper toupee as part of his vice officer’s disguise, who saw his own daughter follow in his footsteps into law enforcement and then routinely outshoot him on the department firing range.

It always came down to the department for Block, who sometimes expressed bitterness and frustration at the way his agency was overshadowed by the LAPD or portrayed negatively in the news. For that, he blamed the media. He blamed The Times. He blamed reporters.

Block had plenty of critics, in high places and low. But some, like the Rev. M. M. Merriweather of Inglewood’s New Mount Pleasant Missionary Baptist Church, forged friendships with the man whose department he had once protested. Eventually that bond led to the two men sharing the pulpit last summer in front of Merriweather’s largely African American congregation--and the unusual sight of the sheriff swaying to the beat of a gospel choir while preaching his agency’s message.

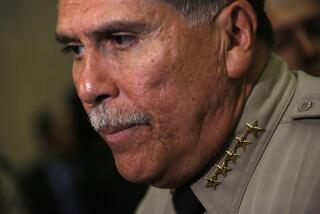

For many, the image of Block was of the public man in the military-style sheriff’s hat waving briskly in community parades and attending ribbon-cutting ceremonies for neighborhood centers, or of him dressed in a conservative suit at news conferences where he defended and touted his 12,000-member department. But the private “Sherm” his friends saw was the guy in golf shirt or knit sweater driving his station wagon on weekend mornings to a Chatsworth deli where he ate breakfast, swapped stories, traded good-natured barbs and chewed over momentous events and small-scale moments before going home to do yardwork.

For Alan Skobin, the sheriff was someone who gave up a gala reception with a visiting Prince Charles to attend a smaller gathering honoring a friend who had just become a third-degree mason. “When one of our friends asked Sherm why he would skip the prince’s reception,” Skobin recalled, “he said: ‘The prince probably won’t remember that I was there, but Alan is my friend, and he’ll remember that I was there for the rest of his life.’ ” Skobin clung to that memory as he recounted just how much he and other members of the “Rat Pack” breakfast club had looked forward to the day when their friend would retire from his high-pressure post.

Then came the fall in the bathtub. The blood clot. The faint signs of a rally. The turn for the worse. And some radio announcer’s voice a week before the election bearing the final news. “We feel like something was stolen from us,” Skobin said. “We’re going to miss him.”

So why did he run again? It was the recurring question in my interviews for a Times Magazine profile of Block I was working on before he died. The piece was postponed after the sheriff was forced into a runoff last spring by Lee Baca, his former subordinate, who eventually won the November race. The plan was to finish the story after the election. A confident Block’s last words to me were an invitation to come back on election night. He promised the outcome would be different than the disappointing primary.

In fact, my lasting memory of that June primary was attending his “victory night” bash and observing the sheriff’s advisors scurrying around with grim looks while their candidate playfully hoisted his young granddaughter in his arms. Afterward, when the somber results were clear, I watched Block depart with a solicitous smile as he made sure the shawl around his wife, Alyce, was in place--seemingly oblivious to everything but her comfort.

Several months later, I replayed those scenes for Block and asked why he didn’t simply retire and spend more time with his children and grandkids, and with Alyce? He laughed. “She’d say to me: ‘There are any number of corporate people and all who probably want to hire you as a consultant or whatever. And I’d say, ‘Why should I go look for a job? I have a job. I’m not out of work.’ ”

One evening last summer, we sat in the front row of a makeshift boxing arena at the sheriff’s training academy. Away from his entourage of aides, we watched the annual match between boxers from the sheriff’s department and the U.S. Marine Corps. As well-wishers approached him and the boxers fought above us, we talked about his early years growing up in Chicago and how he had met Alyce at his family’s deli when she ordered a corn beef on rye. We chatted about his rookie days as a deputy and talked about the rewards and tolls of a law-enforcement life. And when the conversation drifted to his reelection campaign, I broached the subject once more. Why didn’t he just retire and enjoy life, become something like the spectator he was at that moment--safe outside the political ring?

He leaned into my ear amid the roar of the crowd. “See the guys in there fighting?” he said. “Why do you think they get in that ring and get bloodied and battered?” The crowd roared louder, and we all stood in unison as the boxers exchanged a flurry of blows. “They do it because they love it,” Block yelled. “They do it because they need to.” Then he turned toward the ring and joined in the applause and cheering. He looked back at the faces surrounding us. Some fans caught his eye and reacted with waves and more applause until it was hard to tell whether they were cheering the boxers or their sheriff. But it did not matter to Sherman Block. On his face, I saw a broadening smile. I detected the look of triumph. Perhaps it was satisfaction. Certainly it was contentment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.