Kapow!

- Share via

Hey, Mom, you might want to think twice before yanking that comic book out of junior’s hands.

Sure, there are burning skulls, hacked-off arms and gun-toting goons. But here’s a piece of news that may give you pause.

A researcher at Cornell University says that comic books have more challenging words than prime-time television shows, conversation between college graduates--and even some presidential discussions during Watergate.

Comics may be the Rodney Dangerfield of literature, but they also pack a superhero’s Kapow! when it comes to literacy.

“I think you’re getting pretty meaty stuff [in comic books],” said Donald P. Hayes, a Cornell University sociologist and expert on the content of reading materials, including comic books.

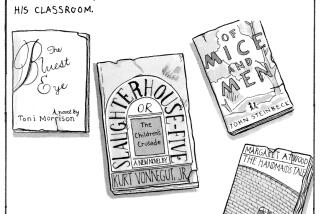

Although most teachers might shudder at the thought of “Superman” or “Wonder Woman” as challenging classroom material, some educators are discovering the upside. They are using comic books--the wholesome variety, of course--to motivate their students and boost vocabulary skills.

For instance, one school librarian in South Los Angeles posts “Captain America,” MAD magazine and other flashy titles at the front door as a way of enticing students.

And a sixth-grade teacher in the San Fernando Valley uses comic books to teach his students about plot structure, setting and other literary conventions.

“It’s too bad comic books are named comic books. They are a serious approach to expressing ideas and concepts,” said Sherry Kerr, an instructional consultant with the Los Angeles Educational Partnership, a nonprofit organization that helps schools adopt reforms. As part of her job, Kerr helps classes create comic books.

“The format is so valuable,” she said. “We need to seize it and bring it back to the realm of education.”

The research may provide the justification.

Comic books fare surprisingly well in a computer analysis of written and oral language by Hayes, a professor emeritus at Cornell. Hayes has developed a program that can analyze the complexity of words used in everything from children’s books to scientific articles, court testimony to adult conversation.

He has found that comics are written at the fifth- or sixth-grade level--with typical words such as “morning,” “given” and “didn’t.”

By contrast, he found words used in radio lyrics, MTV and prime-time television shows are geared to the second- or third-grade level. Also at that level are the average conversations of spouses, college graduates and politicians.

In taped recordings with his chief of staff, President Richard Nixon used words with an average difficulty of second to third grade, according to Hayes’ analysis.

The research underscores the importance of independent reading as the principal avenue for children to build their vocabularies. It also demonstrates that even the simplest texts can contain words that require the reader to use phonics and context to decode their meaning.

“I certainly don’t have the resistance to comics that I had when I began my research,” Hayes said. “When you have such a small space for text, it’s a well-considered kind of writing as a companion to the pictures.”

At The Times’ request, Hayes analyzed the content of “Spawn,” a particularly graphic and wildly popular adult comic series. His verdict: The words in the balloons are written above an eighth-grade level.

Teachers Like the Idea

You don’t have to sell teachers at Hale Middle School on the benefit of comics, albeit of a tamer variety. They have embraced comics with superhero gusto.

Sixth-grade teachers at the San Fernando Valley campus not only use comics for reading, but they also have assigned their students to create comics for a project on ancient Egypt.

One social studies class is studying Egyptian artifacts in preparation for its comic book. A math class is learning how to calculate the dimensions of pyramids, the focus of its own comic book.

Steve Polvy’s class plans to use the Egyptian gods as the main characters in its comic book.

To prepare for the literary adventure, Polvy’s students have been reading a novel about Egypt and scouring the Internet. They also have been leafing through a comic book known as “The Action Files,” a collection of stories about a multiracial group of kids solving mysteries in the fictional seaside town of Park City.

“The kids are totally turned on,” Polvy said. “It lights a fire under some” who might not have read on their own.

Brieanna Kirby already has identified several Egyptian gods that may serve as main characters in the class comic strip. She likes Anubis, the jackal-headed god of embalming, and Bastet, the cat-headed goddess worshiped by those who held felines sacred.

“It’s kind of boring to read someone else’s words in a big history book,” said Brieanna, 12. “We’re kids. We have the point of view of what other kids like. Grown-ups are too old to understand what we like.”

Brieanna may be an exuberant comic lover at school, but her mother takes a dim view of them at home. Most comics, Karen White says, are too violent to earn a place on her kids’ night stands.

Not even “Superman,” that renowned do-gooder and perhaps the nation’s most beloved superhero, is allowed in the house, where Brieanna is the oldest of four children.

“Even though it’s good versus evil, it’s not handled in a way I would like the children seeing,” White said. “If [my children] are acting it out, I don’t want to see them hitting and kicking each other. We’re very much trying to keep everything nonviolent.”

Keenly aware of that sort of sentiment, comic book publishers have tried for nearly half a century to police the content of their products. During the 1950s, they formed a Comics Code Authority that puts a tiny seal on the cover of comic books intended for children.

The seal, found on “Superman” and many other titles, indicates that the comic books avoid “excessively graphic depictions of violence” and never show “graphic sexual activity,” according to the authority.

Such comic books, and the accompanying seal, can be found widely at newsstands and at family-oriented stores, such as Kmart.

Some Push the Envelope

But comic books for the “mature readers”--generally those 18 or older--are not bound by the code. Those comics, typically found in specialty shops, push the envelope of horror and oddity--featuring mass executions, characters with imploded faces and buxom women sitting on the laps of muscle-bound villains.

Comic book sellers say that titles such as “Spawn”--the story of a onetime government soldier resurrected as a disfigured creature from hell--are aimed at their adult customers.

Virtually all the customers at Golden Apple Comics, a Melrose comic book store said to be Los Angeles’ largest, are between 18 and 35, said owner Bill Liebowitz.

He said his employees use discretion when kids come to buy titles such as “Spawn.”

“We tell them, ‘This isn’t for you,’ ” he said. “ ‘If you want to buy this, come back with your parent.’ ”

Back in the classroom, comic book collector and sixth-grade teacher Huy Tran says comics--those meant for kids--are an asset. He keeps 30 or 40 copies for silent reading by students in his room at Foshay Learning Center in South Los Angeles.

He says his students benefit from the vocabulary and the intricate story lines. He even teaches lessons on the history of comic books, making sure to include male and female superheroes.

“It’s good reading,” Tran said. “The vocabulary is pretty sophisticated. They are tools for me to turn the kids on to what they need to learn in regular school.”

GETTING IN TOUCH and MORE ON READING

* If you have questions about this page, send them to Reading Page Editor, Los Angeles Times, Times Mirror Square, Los Angeles, CA 90053 or send e-mail to reading@latimes.com. For stories and activities, see the Kids’ Reading Room in the Southern California Living section every Sunday through Friday.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.