A Long Journey Across the Sea to a Routine Romance

- Share via

David Corstorphine, if we can believe this, had 18 years of a perfect marriage. He and his wife, Rachel, “thought the same things . . . we laughed at the same things . . . we lived the same . . . we were the same.” But Rachel has died of cancer, and David, poor chap, is floundering in grief. His three children are off at boarding school. His parents, Lord and Lady Inchelvie--this is Scotland--hover in concern as David mucks about in the wind and rain like a laborer, restoring the gardens of the family manse.

What David, heir to a distillery that produces an ambrosial single-malt Scotch called Glendurnich, should be doing is attending to business. The firm’s new manager, Duncan Caple, is secretly the agent of a conglomerate that wants to gobble the distillery up. With the aging Lord Inchelvie distracted by David’s woes, and David incapacitated, Duncan has a clear field for his nefarious schemes.

Robin Pilcher, son of bestselling romance author Rosamunde Pilcher, subjects his mother’s formula to the minimum of changes needed to accommodate a male protagonist. “An Ocean Apart” is like a fictional cruise ship. There’s never a doubt about where we’re going: David will find a new love to match the old, and save the distillery in the nick of time. We won’t get there very fast, either: Pilcher, as if to give book buyers their money’s worth, disdains all the narrative shortcuts novelists have devised since the days of Sir Walter Scott. But the amenities are first-class.

Pilcher’s Scotland is a land of traditions as strong and rich as the product of Glendurnich’s stills. It’s peopled with faithful retainers, loyal workers, doughty veterans, cricketers and dog lovers. The Scotland of “Trainspotting,” let’s say, is nowhere in view.

Still, it’s a land Pilcher knows intimately. This isn’t true of the United States, where he is audacious or foolish enough to set at least half of the novel.

Duncan sends David to New York to negotiate with a new distributor, which has hidden links to the conglomerate. Ostensibly, it’s to give the widower a change of scene and something to do; in fact, Duncan is setting David up for a fall. The meeting is a disaster. Depressed and flu-ridden, David is about to give up on life when fate (and an author with no end of handy contrivances in store) comes to his rescue.

David has been bunking with an old regimental chum whose artist sister is about to go to Europe. He agrees to house-sit for her--a charming saltbox on the Long Island shore--and care for her Volkswagen and dog. He sees a job listing for a handyman and, on impulse, takes it, seeking refuge again in mindless toil, but his very first client turns out to be beautiful Jennifer Newman, an ad executive with an often-absent, unfaithful husband and a son, Benji, in desperate need of some fathering.

Though David may have been a wreck only days before, there proves to be nothing he can’t do at the Newmans’, where he is soon dubbed “Superman.” He spruces up the grounds. He fills in at tennis, drubs the most arrogant of Jennifer’s bosses, then diplomatically lets the man win. He teaches Benji to play the ukulele (having himself been a rock musician at Oxford) and finds ways to make the kid popular at school. Jennifer falls for him--if only this sensitive, handsome, amazingly talented guy weren’t just a gardener. . . .

There’s probably no point in wondering how David can be so helpless at first when, underneath, he’s really so strong. It’s a convention of the genre, which requires Pilcher to lay on the primal emotions in thick, rough strokes. He is defter with the machinations of business, the monkeyshines of children, the sheer logistics of transoceanic life--the phones and faxes, limos and plane reservations, the who-does-this-while-the-others-do-that. He fills his pages with incident and scenery, though his New York seems strangely genteel and his Yanks--even the Newmans’ African American housekeeper, Jasmine--talk, try as he might, unmistakably like Brits.

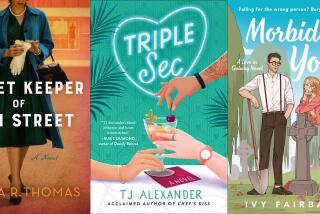

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.