Counsel for the Defense

- Share via

He listened, suffering in silence, to the sounds of happy, shouting children as he sat on his grandmother’s front porch, forbidden to join them.

Forbidden to walk.

Forbidden to leave the porch.

Forbidden to be a child.

He was allowed only to sit and watch children riding bikes; kicking, throwing or batting balls out front, in the street, where he yearned to be.

“I’d try inching my way off the porch, toward the kids, and I’d hear, ‘Pole! You get back on this porch!’ ” Michael Cooper remembers.

Cooper was 10, so skinny his grandmother called him “Pole,” short for beanpole.

When he was 4, he’d fallen onto an open coffee can, cutting his left knee to the bone. Forty years later, the long scar is still half an inch wide.

“It took 105 stitches to close,” recalled the former Laker, now coach of the Sparks of the WNBA.

“I was in a wheelchair for eight months, then on crutches and then I wore a brace for six years,

“The worst part was school. I had to eat my lunch in the cafeteria. Other kids got to sit outside. And after school, when the other kids went to the playground, I could only watch.”

He says today his loving grandmother overprotected him, that he had to overcome atrophy in his left leg when, years after the fall, he finally was cleared for playground activity.

And when he was cleared for playground activity, he took to it just as you would imagine any future NBA star would--more or less as his Spark basketball team has taken to the 2000 season.

The Sparks are playing exactly as he’d told them they would in training camp, and having fun doing it. But then, what team ever won 12 in a row without having fun?

“Coop told us on Day 1 that we would not only be the best defensive team in the league, but that we would be the best-conditioned team too,” says forward DeLisha Milton.

“He told us if we went in that direction, we’d win the championship and I believe him.”

The winning streak--it could hit 13 tonight against the expansion Portland Fire--has been stitched together by a team that usually:

* Plays its best, most tenacious basketball in the final minutes. At Sacramento last week, for example, the Sparks closed the game with a 16-3 run.

* Manages to hold opponents’ most productive offensive players at or under their averages. Utah’s Adrienne Goodson, a 16.7-point scorer, for example, had zero at halftime Sunday when guarded by Mwadi Mabika.

As a coach, Cooper may be in his brightest spotlight yet Friday night, when the Sparks play Houston at the Great Western Forum. The Comets will play Sacramento on Wednesday and if both teams have won their earlier games this week, Friday’s meeting shapes up as the biggest regular-season game in WNBA history. The Sparks could be riding a 13-game streak, the Comets a 10-game streak.

*

Cooper was asked recently if coaching in a women’s league would have seemed farfetched to him a decade ago.

“No, because I was coaching women then,” he said.

Cooper coached in the best-known Los Angeles women’s summer league before the WNBA came along, the Say No Classic. Among the players were Lisa Leslie, now a Spark, and Houston’s Tina Thompson.

He talked recently about differences he has observed in the men’s and women’s games and one of his observations might raise some eyebrows.

“I think women compete better than men,” he said.

“In the men’s game, teams have maybe five guys who’ll compete, right to the end of the game, no matter what. The others will compete until things start to go wrong, then they quit competing.

“With this team I have now, I have 11 players who compete for you all the way to the finish, no matter what. To me, [Allison] Feaster [a sub] is the perfect example of this. I know how badly she wants more minutes, but she gives us everything she has every second she’s on the court.

“That’s the joy I get out of this--the way we’re winning these games, by competing for 40 minutes.”

It’s how Cooper played the game. It’s how he expects his players to play.

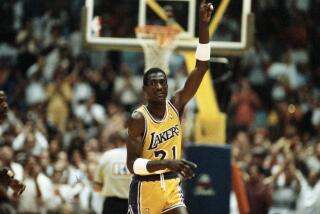

A 6-foot-7 guard who played a spidery, relentless defensive style, he was the stopper on Laker teams that won five NBA championships. His trademarks were knee-high, plain white socks and the drawstring dangling outside, instead of inside, his shorts.

Boston’s Larry Bird once called him “the best defender who ever guarded me.”

On another occasion, Bird told a Boston reporter, “In the off-season, when I’m shooting by myself, Cooper is the guy I imagine guarding me.”

Cooper’s reaction?

“You can win a lot of awards, but when someone you respect as much as I respected Larry says that about you, it means a lot.

“I watched a lot of tape on guys like Larry and George Gervin, guys who were really hard to guard. I’d get a sense of where they wanted to be on the court when they got the ball, and from there, which direction they liked to go. And I just tried to get there, anticipate, and prevent it.

“Defense is just effort. I told my players I’ll never take them out if their shots aren’t falling. That happens to everyone. But they know if I think they’re not playing their hardest on defense, they’re coming out.”

Cooper allows no fooling around out there, no throwing the ball into the seats after big wins--as Cooper himself did in 1987, after the sixth and deciding game of the Los Angeles-Boston NBA finals at Boston Garden.

The game has been playing lately on the NBA Classics channel and Cooper can’t bear to watch. The Lakers won, 106-93, and Cooper had the ball in his hands with one second to go. He threw it and ran off the court as the horn sounded.

“It makes me sick, just thinking about it,” he said. “That ball went right back into the Celtics’ ball rack. It should be in Jerry Buss’ trophy case.”

The five NBA championship rings he won in his 12-season Laker career?

“My [former] wife [Wanda] has them, locked up in a safe-deposit box,” he said.

“I’ve never worn them. Other than the memories they bring back to me, they don’t mean that much to me. Besides, I don’t wear jewelry. I never wore a watch until nine years ago, when Jerry West made me a special assistant. Until then, I never had to know what time it was.”

Cooper was known as something of a zany as a player.

A teammate, once finding a screw on the floor, handed it to Cooper, saying: “Here, this is the loose screw you have--it fell out.”

Cooper kept it in his locker for years.

When it all ended, when the Lakers waived him in 1990 so he could sign a three-year, $5-million deal--his highest Laker salary was $612,000--with an Italian team, tears flowed.

“This is hard,” he said at a Forum news conference, his voice quavering and tears filling his eyes.

During the ceremony, announcer Chick Hearn, who’d dubbed Cooper’s soaring dunks the “Coop-a-Loop,” lost it. Tears streamed down his face as he said, “Thank you, Michael, for the greatest memories anyone could ask for. It’s the end of an era.”

As the 60th pick--third round--of the 1978 draft, Cooper could look back on eight times being named to the league’s all-defensive team, five times to the first team.

After starting out at Pasadena High School and Pasadena City College, Cooper went to New Mexico to play for Norm Ellenberger.

“Ellenberger told me if I played tough defense against our opponents’ best scorers, that would get me into the NBA,” Cooper said. “When I saw Jerry West coming to our games, I figured he was right.”

Cooper was an early candidate to coach the first Sparks team, in 1997, when the WNBA was gearing up. But after two coaching changes, another former Laker, Orlando Woolridge was hired. His first move was to make Cooper his $18,000-a-year assistant.

Then, in a move that has yet to be explained, Woolridge was abruptly fired by club President Johnny Buss after a 20-12 season and replaced by Cooper.

Woolridge and Cooper haven’t spoken since, and it troubles Cooper.

Choosing his words carefully, Cooper said: “The obvious conclusion is that Orlando feels I had something to do with his leaving, but it’s not true. I was totally supportive of him. But he’s never returned my calls, so that’s where it is.”

His former teammates might recall Cooper as an off-the-wall guy but he projects no such image today.

He rarely leaves his coaching seat to protest a call or talk to a player. He probably leads the league’s coaches in seated minutes.

When he is up, he is impeccably attired in one of his $1,000 suits.

And this, of course, should be a felony: He weighs 168 pounds, seven pounds under his playing weight. Only during his time in Italy did Cooper ever weigh more than 180.

“Being so thin enabled me to get by a lot of picks,” he said. “It’s hard to pick a toothpick.”

Cooper and Wanda are divorced, but he shares custody of their three children, Michael II, 19; Simone, 17, and Miles, 10. They live with their mother in Albuquerque, N.M., but frequently visit their father in Los Angeles.

He’s a jazz buff, likes an occasional shot of tequila and a beer chaser, but is never far from the game he loves.

“Even if I’m on vacation,” he said. “I may physically be somewhere, maybe even talking to someone, but in the back of my mind, I’m thinking of the easiest, simplest way to score a basket, or to defend someone. Or I’m thinking about how to make basic basketball plays work.”

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.