David Williams Dies; Was First Black Federal Judge in West

- Share via

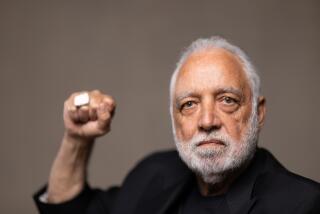

Judge David W. Williams, a tough sentencer who became the first black federal judge west of the Mississippi, died Saturday at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He was 90.

The cause of death was pneumonia, said his son David W. Williams of Orono, Minn.

Williams was a lifelong Republican who fought civil rights battles for blacks in the 1940s and 1950s and took on difficult assignments as a judge, including presiding over about 4,000 criminal cases stemming from the 1965 Watts riots.

Although he took senior status 20 years ago, meaning he could work as little as he wanted without jeopardizing his pay, Williams remained an active member of the U.S. district court in Los Angeles until his death. He was hospitalized in late March after returning from a Caribbean cruise, but continued to review cases--habeas corpus petitions from inmates--in his sickbed.

“He was a beloved figure on this court . . . the epitome of what a senior judge can be,” said Chief U.S. District Judge Terry J. Hatter Jr.

Williams was a native of Atlanta but grew up in South-Central Los Angeles. After graduating from Jefferson High School in 1929, he worked his way through UCLA and law school at USC by mopping bank floors and running errands at the Pantages Theater in Hollywood. He was admitted to the California bar in 1937.

As a lawyer in the 1940s, he joined a small group of black attorneys who worked with Thurgood Marshall, then head of the legal defense arm of the NAACP, to fight the restrictive covenants that barred minorities from residence in many parts of Los Angeles.

The covenants were declared unconstitutional in 1948, but racist attitudes continued to deter blacks and other minorities from buying homes in white neighborhoods. Williams managed to outwit the bigots when, in the early 1950s, he decided to purchase a lot in one of Los Angeles’ most exclusive areas, Bel-Air. Pretending that he lived out of town, he insisted on negotiating the sale over the telephone. He bought the property, which borders the Bel-Air Country Club, for $20,000.

His future neighbors were outraged when they learned that he was black. “They found out where he was and called him and told him, ‘You can’t move out here. What makes you think you can?’ ” his son recalled. “But he kept building his home. And he lived in it until he died.”

Williams was appointed to the Municipal Court in 1956 and to the Superior Court in 1963. He was elevated to federal district court in 1969 after his nomination by President Nixon. He took senior status in 1981.

He volunteered to handle the bulk of the criminal cases that arose from the Watts riots, a massive job that many judges happily avoided. But to Williams, it was “a badge of courage to take on this herculean task that was also so emotionally charged,” Hatter said.

Hatter, who knew Williams for more than two decades, recalled that they once handled the trials of two former nuns accused of bank robbery. Hatter said he sentenced his nun to eight years in prison while Williams gave his the maximum--20 years. “He was a tough sentencer--no doubt about that,” Hatter said.

Although Williams did not agree with mandatory sentencing--”Some of us judges,” he once said, “feel we are made to be like robots who cannot decide for themselves”--he did not flinch from a 1988 federal narcotics trafficking statute that called for vastly harsher sentences for defendants with two or more prior drug offenses.

In 1989 he became the first judge in California and the second in the country to impose a life sentence under that federal law. The defendant was a small-time drug dealer convicted of possessing only 5.5 ounces of crack cocaine.

It was the first time in 35 years as a judge that Williams had ever given a life sentence without possibility of parole.

As he announced his decision, Williams noted that both he and the defendant were black and that they had grown up within a mile of each other--the judge on 109th Street and the drug dealer on 118th Street in South-Central L.A.

“I know that neighborhood and I know how it’s changed,” he said at the time. “That man is making it one of the neighborhoods you can’t live in. . . . My people are the victims.”

Williams is survived by sons Vaughn, of New York City, and David; and two grandchildren. A memorial service will be held Friday at 11 a.m. at St. Albans Episcopal Church, 580 Hilgard Ave., Westwood.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.