Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom

- Share via

In old Tibet, of course, novels rarely existed. There were poetry and song, there were religious texts and storytellers and narrative in the epic tradition. The novel, though, along with secular history and biography, was all but unknown in the Tibetan language, nor was the written language well adapted to the purpose.

It was not until the 1980s--a relatively enlightened decade in Tibet and China that ended cruelly for both--that Tibetan novels began to appear. Some had been written decades earlier--dreary social-realist works written to demonstrate the cruel nature of the old society and the joy of the masses on their “liberation” by China. Despite their fidelity to official norms, they had to wait for publication, so suspicious was Beijing of any Tibetan voice.By the time they appeared, far more interesting literary movements were afoot that would produce truly realist Tibetan novels. At the same time, many young Chinese writers, disillusioned with the direction of their own culture, found in Tibet an exotic cultural stimulus. Most of the first novels about Tibet to be read in China were written by Chinese.

So where does “Red Poppies,” perhaps the first magical realist “Tibetan” novel to reach the Western market, fit? The publishers claim it is a book that does for Tibet what the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez have done for Colombia. But a more direct parallel--and a more illuminating comparison--might be to Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children.” “Red Poppies” has neither the stature nor complexity of “Midnight’s Children,” but is it, as presented, a Tibetan novel, or is it a hybrid? “Midnight’s Children” is a post-colonial novel about India written in English. “Red Poppies” is a novel set in a pre-colonized Tibetan district, written in Chinese.

The author, Alai, is an ethnic Tibetan from the eastern borderlands of the old Tibetan province of Kham--a place that, though culturally Tibetan, was always politically ambiguous. It was not under the political or religious control of Lhasa, which lies far to the west. In Kham, the Dalai Lama was seen as a remote figure who represented a school of Buddhism--the Gelugpa--that held little sway locally.

To the east lay China, with its equally distant capital. The degree of control exercised by the Chinese empire depended on the condition of the imperial dynasty of the day. If the empire was weak, it could assert influence only through trade or bribery. If it was strong, the imperial armies could punish. Symbolic tribute and taxes would intermittently find their way to the Chinese capital and, sporadically, imperial gifts would filter down through local officials.

By the 19th century, as the Qing Dynasty began to fail, this was a negotiated borderland where local chieftains slugged it out among themselves, bending the knee to imperial authority when strictly necessary but wielding absolute power within their own backyard. In 1905, at the very end of the Qing dynasty, a Chinese general, Zhao Erfang, occupied eastern Tibet and, in a precursor of Chinese Communist policies, began to eliminate the Buddhist clergy with a view to assimilating the territory and populating it with Chinese peasants. After the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, this portion of Tibet’s borderlands was absorbed into the Chinese province of Sichuan.

“Red Poppies” is set between the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911and the victory of the Communist Party in 1949, when the local chieftains were not greatly troubled by Chinese authority: Between the Japanese occupation and the Chinese civil war, no aspiring power in China had the reach to bring the borderlands into line. The chieftains enjoyed an Indian summer of almost untrammeled local power. It was a world that, nevertheless, was doomed to vanish.

“Red Poppies,” Alai’s first novel, tells the story of the Maichis, the family of a powerful local chieftain who holds absolute sway over his servants and slaves and expends his energies in the vigorous enjoyment of sex and the local struggle for power with rival clan chiefs. The wider world and its events--the incursion of Western powers, the politics of distant Lhasa, the continuing wars in China, the Japanese invasion--are filtered through the brief appearances of a series of minor characters.

There is Charles, ostensibly a Western missionary, who is bent on collecting mineral samples. A Chinese official called Huang encourages the Maichis to plant the opium poppy. The chieftain’s daughter, who has married an Englishman, appears only to demand a vast dowry in silver and leave for London. A Gelugpa monk called Wangpo Yeshi arrives from Lhasa to challenge the shamanistic local monks. The chieftain punishes Wangpo Yeshi twice for speaking his mind too directly: the Maichi family executioner cuts out his tongue and he becomes the family’s historian.

The novel’s narrator is the second son, born of a marriage between the chieftain and his second wife, who is Chinese. The boy is considered an idiot, but his idiocy, of course, allows him to challenge the moribund conventions of his father and older brother. The idiot knows the chieftain’s world is doomed.

It is he who marries the most beautiful woman and enlarges the family fortune. Sent to the borders of the family estate, he turns the fortress his brother has built into a trading post, and a flourishing town springs up around it. When the Red Army finally arrives, its officers offer to keep him on as chieftain, but the Maichi world has collapsed; the old chieftain dies in the rubble of his estate and the narrator submits willingly to his own fate in the last act of a revenge drama.

“Red Poppies” stands on its own literary merits, accessible to the reader without the historical background or even a precise geographical fix on the novel’s setting. It stands up to comparison with other examples of contemporary fiction in China--where magical realism is enjoying a vogue, and Alai has demonstrated that he can move from the short story to the long form without losing his grip. But the context helps to challenge the publisher’s bizarre claim that “Red Poppies” dispels “many of the popular myths about a uniformly pacificistic society peopled by devout worshipers.” That mythological Tibet derives from a Western work of popular fiction, James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon,” and was perpetuated in “The Third Eye,” a fantasy first published in 1956 and penned by a man who was not, as he claimed, the son of a “high Tibetan lama” but of a plumber in the English county of Devon. Neither did Tibet any service. “Red Poppies” is a work of fiction, mercifully, of an altogether higher order, but it does the author no favors to treat his literary imagination as though it were a contribution to historical debate.

The question of literary and linguistic identity, though, is more interesting. The Chinese dismemberment of Tibet relocated Alai’s birthplace within the borders of the Chinese province of Sichuan, and Alai, born in 1959, is of a generation that grew up under Chinese rule in a Tibetan cultural environment.

According to the historian Tsering Shakya, as late as the 1930s, only a tiny minority spoke Chinese in Eastern Tibet. With the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, however, that changed. Alai’s age group received schooling in Chinese--even in Lhasa, China has banned the use of Tibetan in university education--and Alai is unable to write in Tibetan. His more famous contemporary, the Tibetan writer Tashi Dawa, neither writes nor speaks it.

For young Tibetan intellectuals, even in the Tibet Autonomous Region, Chinese is the only language of advancement and power for a job, for an education. It is also the language that gives access, in these more liberal cultural times in the People’s Republic, to outside influences. If Alai quotes Walt Whitman, as he does in an earlier short story (“Wind Over the Grasslands”), it is because Whitman is translated into Chinese. And if he writes in magical realist style, it is less to do with Tibetan literary trends than with the fact that a generation of young Chinese writers has adopted it. Like that generation of post-colonial Indian writers who write in English, Alai uses the language of the colonizer--and an imported literary form--to construct his version of the colonized culture.

In Lhasa, too, novels are being written, but for a different readership. According to Yangdon Thondup, a London-based scholar of contemporary Tibetan literature, Tibetan-language novels are unfortunately rarely translated and reach only local readers. China, it seems, is still not interested in the authentic Tibetan voice. Novels like “Red Poppies,” on the other hand, that treat Tibetan subjects in Chinese, are popular in China where they are considered Tibetan. In Tibet they see things differently. Alai himself might be considered Tibetan, but his novel is not . Such novels read strangely to Tibetans, as though they were written for outsiders. It’s a situation that has its own ironies, well illustrated by the success in China of “Red Poppies.” The novel won the Mao Dun Prize, China’s top literary award. No novel written in any of China’s “minority” languages--including Tibetan--is eligible.

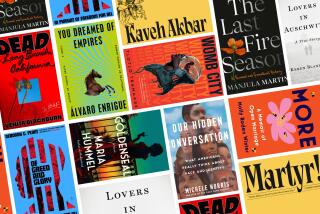

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.