White House Calls on Venezuela to Hold Early Vote

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Abandoning its hands-off approach, the Bush administration said Friday that it was “deeply concerned about the deteriorating situation” in Venezuela and called for early elections.

The White House said the 12-day-old strike organized by opponents of President Hugo Chavez had disrupted the Venezuelan economy and led to the shooting of peaceful demonstrators and to attacks on media outlets.

With negotiations between the two sides at an impasse, early elections promise “the only peaceful and politically viable path to move out of the crisis,” according to a statement read by White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer.

The administration’s decision to suddenly exert pressure -- after keeping a wary distance from Venezuela’s strife for most of this year -- reflected intensifying concern about violence and serious economic damage in the country, officials said.

The new approach also reflected American concern about the disruption in supplies of Venezuelan oil, which represent more than 10% of U.S. oil imports. Venezuela’s oil will be vital if the United States launches a war against Iraq that begins choking off Mideast oil and increasing prices, experts said.

The strike has nearly halted oil shipments from Petroleos de Venezuela, the national oil company, which provides about 50% of the government’s revenue.

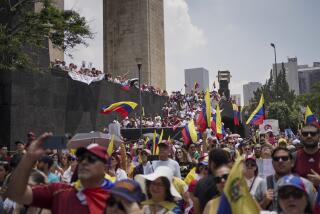

The strike has pitted populist strongman Chavez and his supporters, made up largely of the poor, against a coalition of unions, the Roman Catholic Church, business and professional classes, and private groups such as women’s organizations. Chavez, who has strong support from much of the military, has steadfastly refused the demands of the opposition that he allow a vote that could end his tenure as president.

The United States was accused in April of encouraging plotters of a short-lived coup against Chavez, a charge it strongly denied. Since then, U.S. officials have largely sought to work through the Organization of American States, whose power is confined mostly to persuasion.

But this week in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, OAS and U.S. officials acknowledged that Chavez and his opponents were entrenched in their positions.

“There’s no political will to arrive at an agreement,” Charles Shapiro, the U.S. ambassador to Venezuela, told a Venezuelan newspaper.

Senior U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Colin L. Powell, have begun paying closer attention to developments there in recent days, officials said. On Thursday, Powell dispatched Thomas Shannon, a deputy assistant secretary of State, to Venezuela to meet with the country’s foreign minister.

A key question left unresolved by the U.S. statement Friday was what kind of elections the U.S. favors. Chavez’s supporters and opponents have proposed various elections at different times.

Some opponents have recently been pushing for a quick, nonbinding referendum on the government’s performance. Chavez has repeatedly said the constitution would not permit a referendum until August, midway through his term, though some outsiders are skeptical that he would agree to one.

“The U.S. is simply not choosing among them,” one State Department official said.

Some private experts said the administration’s failure to endorse one of the alternatives showed that the United States has fallen behind the curve in dealing with the issue.

Peter Hakim, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a private Washington policy group, said that a month ago, the call for elections would have had some meaning.

But now, he said, “the entire debate is about when to have the election, and I don’t know how much value this has. I’m afraid we haven’t quite caught up to the train.”

Others said it would be unwise for the U.S. to throw its weight behind one of the alternatives when the situation remains so volatile and murky.

Stephen Johnson, a Latin America specialist at the Heritage Foundation, said there are no political figures who are obvious alternatives to Chavez. Nor has the opposition put forth a well-considered plan for returning the country to democracy, he said.

With such vagaries, “it would be very difficult for anyone in the U.S. government to endorse a specific approach,” he said.

Because of Venezuelan sensitivities about U.S. meddling, many U.S. government officials and outside experts have believed that U.S. officials should keep a low profile and work only within the OAS.

Julia E. Sweig, deputy director for Latin American studies at the Council on Foreign Relations think tank, said she believes that earlier this year, U.S. involvement “may have made things worse.” But because of the deterioration of the situation, “now it can only make things better.”

She said she would like to see senior State Department officials and senior lawmakers, who have also been largely silent, speak up to try to bring pressure on the two sides to reach a settlement.

Even as they signaled increased U.S. interest, U.S. officials asserted that the crisis must be solved in Venezuela.

“While the hemispheric community and other friends will do all they can to help, only Venezuelans themselves can resolve their own problems,” the White House statement said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.