For some with heart disease, exercise can be fatal

- Share via

Running guru Jim Fixx, former Florida Gov. Lawton Chiles and basketball star Reggie Lewis all had something in common. They were regular exercisers who died while working out or just minutes afterward -- rare victims of what researchers have dubbed “sudden death during exercise.”

Decades of studies have shown that frequent exercise significantly reduces the chances of developing heart disease. And failure to work out regularly is widely regarded as a leading risk factor for coronary heart disease.

But less well-known is that some regular exercisers are at a greater risk of having a heart attack at certain times. For them, as with non-exercisers, a heart attack is five to 10 times more likely to occur during jogging, running or other physically strenuous pursuits compared to passive activities, research has shown.

“It’s a paradox,” said Dr. Paul D. Thompson, director of preventive cardiology at Hartford Hospital in Hartford, Conn. “While engaged in the activity, the risk of a heart attack goes up, but after an hour comes back down.”

Heart disease, not exercise, is the primary cause of cardiac arrest in almost all such cases, researchers say. Fixx and Chiles were already at high risk for heart attacks whether they exercised again or not -- because they all had severe coronary artery disease. (Lewis died in 1993 as a result of a heart abnormality.)

Chiles, who died at age 68, had a history of heart troubles and had undergone quadruple bypass surgery more than a decade before his death in 1998. He died while riding his exercise bike, a daily routine he’d taken up to help his condition.

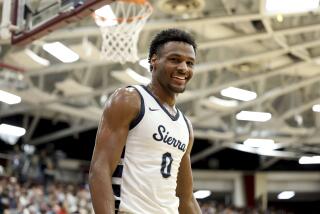

Lewis, a first-round pick of the Boston Celtics, was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after about four years in the NBA, and was advised by most doctors to quit. The 27-year-old, however, received medical clearance to play and died during a pickup basketball game.

Meanwhile, Fixx, whose autopsy showed he had severe coronary artery disease, is believed to have ignored many warning signs of his illness. In addition to having a father who died of heart disease at a relatively young age, Fixx also had elevated cholesterol levels and experienced chest pains. He died while running at age 52 in 1984.

Fixx, as with many other athletes, however, may not have understood his risk. Even though he exercised, it was still no guarantee of heart health, physicians say. Because of his hereditary predisposition to clogged arteries, Fixx was especially vulnerable to a heart attack no matter how much he worked out.

Complicating matters is the fact that even with advanced heart disease, people can still perform astounding physical feats. One 1987 study of marathon runners found that of those who died in sudden death circumstances, more than 80% had continued to exercise despite experiencing either chest or abdominal pain and other classic symptoms of a heart attack.

Researchers have found that athletes are adept at ignoring discomfort, one of the traits that allows them to become good athletes. But the downside is they often ignore even alarming physical symptoms and fail to seek the proper medical attention at their own peril.

It’s a difficult scenario to study because of its relative infrequency -- sudden death occurs about once per 900,000 hours of physical activity in the general U.S. population. But researchers have collected enough data to know that anyone with a personal or family history of heart disease should consult a doctor before either beginning or ramping up a fitness routine. Also, anyone with high blood pressure, high cholesterol or diabetes should consult a doctor.

Even if you don’t exhibit symptoms or are just ignoring them, a maximal heart-rate test with a cardiologist can often determine whether you’re at risk of sudden death. Dr. Herman Falsetti, a cardiologist with the Health Corp. in Irvine said the key is to push the subject to the brink of failure in either the heart or the legs. The test isn’t usually covered by insurance and costs between $450 and $600.

“Exercise is really a quality of life issue,” added Falsetti, who has advised elite endurance and racing athletes. “When you’re in better shape, you feel healthier, you’re more vigorous and you can enjoy life more.” It’s sometimes easy for the public, especially after high-profile examples of sudden death make headlines, to reason that exercise isn’t really a deterrent to heart disease after all. But research has consistently shown that is the wrong conclusion.

Thompson, author of “Exercise & Sports Cardiology” (McGraw-Hill, 2001), has studied the link between exercise and heart disease for more than two decades and has calculated that a middle-aged jogger with no history of heart problems is still at much lower risk for sudden death than a non-exercising counterpart driving his car.

“The risk is always greater if you don’t do anything,” said Thompson.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.