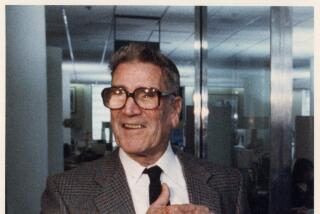

Roy Jenkins, 82; British Statesman, Biographer and Social Crusader

- Share via

LONDON — Roy Jenkins, a British statesman and man of letters who almost became prime minister and then wrote acclaimed biographies of some who did, died of a suspected heart attack Sunday at age 82.

He was widely regarded as the leading liberal voice of his generation.

The son of a miner and a Labor parliamentarian from the Welsh coal valleys, Jenkins was steeped in the socialist politics of postwar Britain.

He was first elected to Parliament as a member of the Labor Party in 1948, but gradually withdrew his affections from the party, even while rising to two of the most senior Cabinet positions in the 1960s Labor governments of Harold Wilson.

Instead, Jenkins’ politics increasingly tacked toward the instincts of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whom he watched admiringly from across the floor of the House of Commons for nearly 17 years.

Churchill was then a “remote deity to me,” Jenkins later wrote of those early political years.

But Jenkins would come to emulate many of his hero’s traits, including the maverick’s willingness to switch parties and a love for fine food and wine that led one colleague to despairingly note: “Roy is more of a socialite than a socialist.”

In 2001, Jenkins wrote a biography of Churchill that was hailed as a masterpiece of modern political writing.

He also was the author of an acclaimed biography of towering 19th century Prime Minister William Gladstone, as well as 15 other books, including one on Harry S. Truman.

But by the time he turned his energy to chronicling the careers of other great leaders, Jenkins had left his own deep impression on British politics. In office, he matched his crusader’s language with legislative reforms.

As home secretary, the Cabinet minister responsible for criminal justice, Jenkins pushed through an agenda that included decriminalizing homosexuality, easing divorce proceedings, legalizing abortion and abolishing the government’s power to censure theatrical entertainment.

He later served as chancellor of the exchequer and again as home secretary in 1974. An ardent champion of deeper British integration with Europe, he was president of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981.

But Jenkins’ most controversial role -- as the formidable operator who helped rearrange his country’s political alignment -- was still to come.

Openly impatient with the doctrinaire socialism of the majority of his Labor colleagues, he bolted the party in 1981 with a boldness that temporarily whispered the promise of a new day in British politics.

Along with three other moderate politicians (therefore composing what became known as the Gang of Four), Jenkins created the Social Democratic Party, becoming its leader a year later.

But the party never got electoral results to match its early promise, and eventually was forced to merge with the Liberal Party to form the Liberal Democrats.

Nevertheless, the Social Democratic Party is now widely regarded as the archetype for the reformed and modernized Labor Party that Tony Blair led to power in 1997, stripped of its socialist platform, no longer threatening to middle-class voters.

Jenkins was the “grandfather of New Labor,” former Labor Minister Tony Benn said Sunday.

The Social Democratic Party, Benn contended, “was Roy Jenkins’ idea of what Labor should be.”

Yet for all those who say Blair’s rise could not have happened without Jenkins, there are others who claim the conservative Margaret Thatcher era wouldn’t have occurred without him either.

“Without Roy, Thatcher would really never have happened,” said Dennis Healey, another former Labor minister and a colleague, friend and frequent rival of Jenkins from their days together at Oxford University in the 1940s.

Healey and others like him argue that Jenkins should have pushed for change from within the Labor Party.

By walking out, they say, he helped split the progressive center-left vote, which allowed Thatcher’s Conservatives to win reelection handily in 1983. The Tories would not lose power until 1997.

Jenkins resigned the Social Democratic Party’s leadership in 1983, but remained engaged in British politics.

In 1987, he entered the House of Lords, where he continued to make the case for further British integration into European affairs even as that view became a minority one.

His influence returned with the rise of Blair, who regarded Jenkins as a mentor and advisor.

“He was a friend and support to me, and someone I was proud to know as a politician and as a human being,” Blair said Sunday.

Their relationship endured a few bumps. When he became prime minister, Blair asked Jenkins to head a commission looking into ways to reform the British parliamentary system. Its mandate included examining whether Britain should consider a form of proportional representation, long one of Jenkins’ causes and one that his report recommended.

But Blair, who would likely find himself with greater parliamentary opposition should the current system be altered, quietly shelved the report, to Jenkins’ dismay.

Their friendship also apparently survived an interview Jenkins gave to the conservative magazine the Spectator in 2000, in which he suggested the prime minister has a “second-rate mind.” But Blair also talked about the wisdom and humility he gleaned from Jenkins.

While opening a physics center at Durham University last year, the prime minster recalled seeing Jenkins gazing into space before doing a radio interview.

When Blair asked why he looked so thoughtful, Jenkins replied: “I’m just contemplating the vast expanse of my own ignorance.”

Jenkins is survived by his wife, Dame Jennifer Jenkins; and two children.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.