A wrestler’s widow remembers his pills, hormone injections

- Share via

Another wrestler has died young and Melanie King is not surprised.

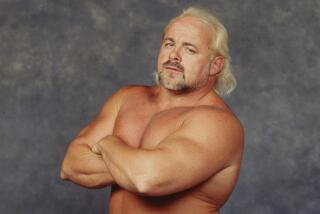

She recalls her reaction 5 1/2 years ago when authorities informed her by telephone that her husband, professional wrestling star Brian Pillman, was dead.

“I’m not saying I expected it,” King said, “but I was not as surprised as the wife of a 35-year-old should be.”

Pillman’s body was discovered Oct. 5, 1997, inside his hotel room in Minneapolis, a World Wrestling Federation stop. Although the Hennepin County medical examiner listed the cause of Pillman’s death as coronary artery disease, nonlethal traces of cocaine were found in his system. And King, who has since remarried, says that’s not all her late husband was taking.

She says Pillman was swallowing pain pills illegally prescribed by an Indianapolis doctor; that he was taking ephedrine-containing pills to keep his weight down and give him the “cut” look wrestlers crave; and that he was spending $1,600 monthly for HGH -- human growth hormone, a muscle-building compound even more powerful than steroids.

Mitchel Morey, the coroner who examined Pillman, said he could not conclusively identify steroids and HGH as factors in the wrestler’s death, nor did he rule them out.

Pillman’s “post-mortem definitely warrants further examination,” Morey said. “What’s really needed are studies of enough people over a long period so we can better address steroids and to see if we can ferret out a real answer on this thing.”

King doesn’t need a scientific explanation. She believes Pillman’s drive to return to wrestling’s major leagues is what killed him. Pillman’s troubles, she said, started when he injured his left leg in a one-vehicle crash in April 1996, a time that coincided with the anticipated start of what was expected to be a spirited -- and lucrative -- bidding war for his services between WWF and World Championship Wrestling.

Pillman was hoping to negotiate a new contract that would pay him in the neighborhood of $500,000 annually, and seeing dollar signs, rushed his return.

“Brian’s leg was obliterated,” King said. “He probably never should have come back.”

But he did, and the WWF promotional machine shifted into high gear to greet him by working up a provocative story. As Pillman’s return was hyped in a television segment in which rival Steve “Stone Cold” Austin was shown breaking into Pillman’s home -- a stunt intended to heat up a rivalry -- King said Pillman’s comeback was progressing as a troubled, drug-aided pursuit.

“He’d inject [the HGH] under the skin once or twice a day from July 1996 to April 1997,” King said. “I saw him doing it a few times and it scared me. I said, ‘Why are you doing this? Doctors give injections, not you.’ ”

Vince McMahon, who founded the major league of wrestling -- then the WWF, now the WWE: World Wrestling Entertainment -- conducted a televised interview with King the night after Pillman’s death.

McMahon asked her how she planned to care for her four children -- she was two weeks’ pregnant with Skylar, now 4, when Pillman died.

“Vince told me I didn’t have to do the interview if I didn’t want to, but I felt obligated to him,” King said. “I knew he wanted me to do it and I knew I would be relying on this man for food.”

King said McMahon paid her the $50,000 balance of Pillman’s first-year contract, sent her $65,000 after a memorial wrestling show he organized, and gave her $12,000 to make a down payment on a home.

That support, and her belief that “Brian was a grown man who made his own choices,” helped her decide not to file a wrongful death lawsuit against the WWF.

King, who makes $10.50 an hour as an accounts receivable clerk for her father-in-law’s Kentucky trucking company, said she now regrets that decision. The WWE did not make McMahon available for comment.

King said the WWE needs to reexamine what she calls the root of the situation: the schedule. Too much travel, too many matches, and too much time spent at promotional events.

If two dozen deaths among professional wrestlers 45 and younger the past five years can be considered evidence of a perilous tradeoff between living well and living dangerously, King offers this warning:

“The money you make ... you pay for it in every way.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.