One Voice on Piracy

- Share via

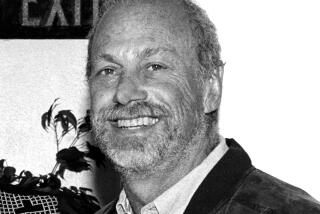

Warner Music Group Chairman Roger Ames wouldn’t budge. The industry veteran refused last summer to join an effort by his four major competitors to sue illegal downloaders who were crushing the industry’s bottom line.

Ames insisted that before the labels unleashed their attorneys and risked a potential public relations backlash, they needed to provide consumers with an alternative, a place where the pirates could legally download songs from all five major record companies.

“We made it clear to everyone that we weren’t prepared to go forward with lawsuits until there were attractive and comprehensive online services up and running,” said David Johnson, Warner Music’s general counsel.

Warner Music’s cooperation was crucial.

“If there had been division among the major record companies, it would’ve given license for a lot of other people to take contrarian views,” said Hilary Rosen, who was then the industry’s top lobbyist as head of the Recording Industry Assn. of America.

In the end, Ames’ resistance forced the labels to put aside their cutthroat rivalries and agree for the first time to sell songs from all the companies on two label-owned online services.

“People realized this wasn’t ‘Let’s see if we can sweet-talk Roger into this over a beer,” said one executive familiar with the contentious, yearlong negotiations that on Monday led to the filing of 261 lawsuits against a nationwide assortment of alleged pirates.

As the effort to enlist Warner Music’s support illustrates, the decision to take legal action did not come easily or quickly. The deliberations among the fiercely competitive big five record companies were plagued by distrust and conflicting agendas, which is often the case when they are forced to confront industrywide issues.

The fact that agreement ultimately was reached, however, is testament to the shared miseries and desperation of the record companies owned by AOL Time Warner Inc., Vivendi Universal, Sony Corp., Bertelsmann and EMI Group.

Last year alone, piracy was blamed for siphoning about $10 billion from global music sales. Even before this week’s lawsuits, the labels had coalesced to combat illegal downloading by taking legal action against a variety of file-sharing networks but failed to put a dent in the pirate population.

Hauling individual downloaders into court seemed the only option left to the labels, which had been feuding with one another over Internet strategies as the problems they jointly faced only worsened.

Bertelsmann, for example, had outraged its competitors in 2000 by providing financial support to ailing Napster Inc., the pioneering online service that allowed music fans to obtain free songs with a click of the mouse. The purchase came at a time when the German company’s BMG music division had joined the industry’s lawsuits against the file-swapping network.

Some labels also questioned Warner Music’s resolve to fix the problem, fearing that parent AOL Time Warner would soft-pedal any anti-piracy litigation that could threaten its America Online unit.

Last summer, several labels resisted Ames’ demand that they “cross-license” their music for sale on two separate sites financed by the five companies. Some thought there was no time to waste on tangled talks. Wary of giving the slightest edge to a competitor, they could not even agree on how the music would be made available and at what price. In all, it took six months for the labels to reach an agreement.

Litigators for record conglomerates had kicked around the idea of suing individuals for years, at least since Napster popularized file swapping in 1999, sources said. But the attorneys hadn’t pushed the idea, fearing a public relations disaster.

But by last summer, the piracy crisis had become so severe that lawyers for the major record companies believed their bosses would finally pull the trigger.

Universal executives, who had discussed the plan internally, favored litigation against individual downloaders from the outset.

“No one relished the idea,” said Universal Music President Zach Horowitz. But, he said, “artists and songwriters were losing their livelihoods. Retail stores were closing. Employees at music companies were being laid off. The message wasn’t getting across that the underlying behavior was illegal and wrong.”

Top executives from the other music giants, including Sony Music and EMI, chewed over the potential backlash against the industry that probably would follow the litigation but also decided to sign on.

“The PR issues are always there in the front of people’s minds. But you either let that run the agenda, or you get your best PR in place and then deal” with any bad publicity, said David Munns, chief executive of EMI’s North American division. “Basically, people realized we didn’t have a choice.”

Among those who shared that conclusion were BMG Chief Operating Officer Michael Smellie and Sony Music Executive Vice President Michele Anthony.

Now, with the decisions and planning for the lawsuits behind them, the labels continue to wage their battles on other fronts.

Just last week, Universal announced that it planned to slash CD prices by at least 25%, a turn that knocked competitors back on their heels and could shake up the industry’s underlying economics. Privately, rival executives at some labels criticize the move as a short-sighted effort to inflate sales. Warner publicly announced that it didn’t plan to follow suit.

“These companies are extremely competitive and the executives are extremely competitive with each other,” said Rosen, the RIAA’s former chief. “When everyone’s together, they are a powerful force. But it’s hard to get them there.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.