How can a Botox nation boo Bonds?

- Share via

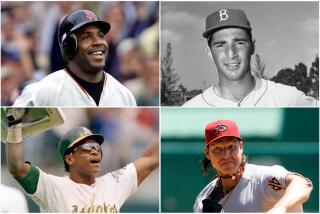

AMERICA THIS spring has been treated to a most remarkable sight. One of the greatest hitters in baseball history, holder of almost unfathomable records, is closing in on one of Babe Ruth’s iconic milestones. Yet the commissioner of Major League Baseball didn’t even walk across the street to the ballpark when the slugger was in town, and fans boo the perennial all-star at every turn. The San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds has been voted his league’s most valuable player seven times (no other player has won the accolade more than three times), is the godson of folk-hero Willie Mays and holds a college degree in criminology to boot -- and yet the journalists who chronicle his heroics hardly have a good word to say about him.

The reason, of course, is that Bonds is widely believed to have achieved his latest feats through foul means, turning to steroids to convert his lean, fleet figure into a bulked-up phenomenon that looks like an ad from Cyborg Today. Several other baseball stars have confessed to resorting to illegal aids -- they needed to, they say, to keep up with the others -- but every mumble of innocence from Bonds only increases the public outrage as reporters describe his alleged malfeasance and federal investigators discuss whether he has committed perjury.

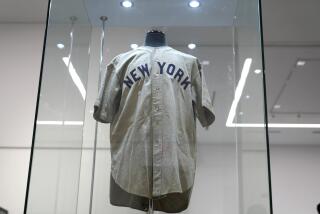

Bonds may not be stripped of his records, as sprinter Ben Johnson was of his gold medal in the 1988 Olympics, but many say his name should be attended by an asterisk; poor Ruth had nothing to help him toward 714 home runs but alcohol and philandering.

Yet look closer. Americans are complaining about foul play and Bonds’ remaking of his body at a time when citizens are turning to Botox to erase facial lines or to Viagra to pump up their manhood. They’re taking Prozac to stay happy, going to the pharmacy to regrow their hair and boosting the ratings of TV reality shows about glamorous makeovers. In such a context, it’s easy to suspect that it’s not baseball that’s the national pastime but gaudy reinvention.

At just the time that Bonds began his latest run on history, 19-year-old Kaavya Viswanathan was rivaling him by compressing a career’s worth of headlines into a few weeks. At the beginning of April, the Harvard sophomore was in all the papers for receiving a reported $500,000 advance for her debut novel, “How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life,” about an academically pressured young woman who decides to round herself out. By this month she was in the same papers when it was revealed that phrase after phrase from the wonder girl’s novel were taken from another source. Opal Mehta got a new life, it seemed, by purloining someone else’s.

It’s not hard to suspect that the ambitious Viswanathan was not just the perpetrator of a deceit but, in another way, the victim of a larger lie -- that achievement is its own defense and that a resume (even at 19) is more important than a life. All she was doing, she might have said, was emulating those CEOs, ever more in the news recently, who doctor their resumes or plagiarize their wisdom.

Bonds has said that he owes it to the public to hit home runs -- to offer drama on his TV reality show and website -- and that he will do anything he can to get the job done. If he is eventually found guilty of using enhancement drugs, it seems safe to say, another Frankenstein athlete will soon come along, ready to do anything he can to break Bonds’ marks.

When Henry Aaron overtook Ruth’s record for homers in a career in 1974, he too was snubbed by the baseball commissioner and by much of the nation. In the year leading up to his record-breaking homer, he wrote in his autobiography, he received 935,000 letters, many beginning “Dear Jungle Bunny” or threatening death to his family members or himself if he continued his quest to eclipse the Babe. His crime, apparently, was being a black man daring to break a white man’s record.

We’ve come a long way in 32 years, we may say, because in Bonds’ case, race is not a major issue (except in the slugger’s own mind). But then a weirdly overmuscled figure barrels up to the plate, the boos rise up across the nation from the artificially pumped-up and fresh-faced, and it becomes hard to say we’ve moved ahead at all. Perhaps it’s not Bonds who needs an asterisk but 21st century America.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.