Indians’ ace headed home an All-Star

- Share via

CLEVELAND — Photos of a smiling Carsten Charles Sabathia adorn a cabinet door on his son’s locker, mementos of the man who accidentally bought his kid a baseball glove for the wrong hand, turning him into a lefty.

“Look at him,” C.C. Sabathia says, pointing to a favorite shot of his dad, arms raised above his head and wearing a gray No. 52 Indians jersey as he soaked up a glorious day at Jacobs Field. “He was such a fan. He just loved it.”

Sabathia misses his father, who died in 2003 just before his grandson, Carsten Charles III or “Little C,” a 3-year-old spitting image of his daddy, was born.

Before he passed away, the elder Sabathia would dream aloud about one day seeing his kid pitch in an All-Star game -- by San Francisco Bay.

“He always talked about, ‘When the game comes to San Fran,’ ” said Sabathia, who grew up in Vallejo, Calif., not far from the Golden Gate Bridge. “He was all excited when the Giants got a new ballpark because they’d be getting the All-Star game. He was like, ‘I know you’re going to be there.’

“That’s all that I’ve been thinking about all year,” the Indians’ ace said. “Those words from him.”

Sabathia has fulfilled his father’s prophecy.

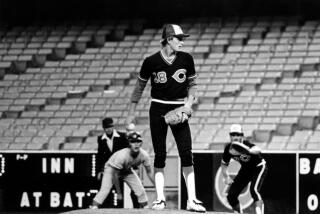

At 12-3 and off to the best start of his career, the 26-year-old left-hander was named to his third AL All-Star team and will pitch in front of family and friends in Tuesday’s game at AT&T; Park, the Giants’ waterfront home.

He was mentioned as a possible AL starter but lost his last game before the break -- giving up three homers and a season-high seven runs in four innings against the Tigers. Detroit Manager Jim Leyland was to pick the AL starter.

Sabathia, who nearly buckled under the enormous pressure of trying to become Cleveland’s No. 1 starter, is that and more for the Indians, who led the Tigers by a game in the AL Central heading into this weekend.

Once prone to emotional blowups on the mound, Sabathia has matured into one of baseball’s elite pitchers, one who demands attention every time he takes the ball.

“He’s one of the best in the game, no doubt, and he has been for a while,” said Eric Wedge, in his fifth year as Cleveland’s manager. “When that guy goes out there it’s a different day. I played with Roger Clemens in Boston, and it was a different day when Clemens pitched -- for both teams, for the fans, for the media. That’s how it is with C.C.”

Sabathia thought he had it all figured out during his first seasons with Cleveland. A first-round draft pick in 1998, he rocketed through Cleveland’s minor league system, skipping past triple A to join the Indians as a 19-year-old starter in 2001.

On a playoff-bound team of veterans, he was the can’t-miss kid, and after going 17-5 as a rookie, Sabathia got full of himself. His weight -- always a concern -- ballooned well over 300 pounds and his ego swelled at perhaps an even more alarming rate. Looking back, there were warning signs. Sabathia ignored them all.

“It definitely hurt me,” Sabathia says of his first season. “I didn’t do anything in that offseason, and I went into the 2002 season thinking, ‘Oh yeah, I can go out there and win 16 or 17 games no problem.’ I thought it was just that easy. I felt I could throw my jock out there and win.”

He posted 13 wins in each of the next two years, but an 11-10 finish in 2004 didn’t fully explain a season in which Sabathia, who lost his father, uncle and a close friend in a short span, constantly argued with umpires while losing his composure during uneven starts.

Sabathia was unraveling, and he knew exactly what the problem was: He couldn’t control his temper or his pitches.

“It’s been that way since I was 5 or 6 years old,” he said, relaxing in the clubhouse recently after a visit to the weight room. “On the field, I’d get frustrated. Just make me mad, that was the secret everybody knows back home.”

Back in ‘04, Sabathia’s troubles were a major concern for the Indians, who were counting on his steadiness to help get them through a transition period when they fell from perennial AL power to also-ran.

Cleveland fans, spoiled by an unprecedented run of division titles and two World Series appearances after decades of misery, began to wonder if Sabathia ever would reach his enormous potential. He began to have doubts of his own and found the burden of expectations too much.

The Indians, who haven’t had a 20-game winner since Gaylord Perry in 1974, needed him to be their next one.

“I put way too much pressure on myself,” he said. “If it was anybody’s fault, it was mine.”

But the harder he tried, the worse things got.

His troubles multiplied in 2005. He began the season on the disabled list -- a career first -- because of an abdominal strain he suffered while warming up for his first start of spring training. After returning, he went 0-3 in June and was 1-5 in July.

“I was getting my butt kicked,” he said.

And it didn’t take long to figure out why. Sabathia was tipping his pitches with each delivery. Sometimes his lead arm dipped lower for a fastball. He would bend his knee deeper on a curveball.

“It was a lot of things,” pitching coach Carl Willis said.

So Sabathia, Willis and bullpen coach Luis Isaac went to work on fixing Sabathia’s mechanics and they developed a new pitch: a cut fastball that devastated right-handed hitters.

Sabathia began to see immediate progress, which in turn helped him get his emotions under control.

“He would lose his focus in the middle of the game,” Willis said. “Now he’s as calm and collected as anyone you’ll see.”

There are still times when Sabathia shows emotion, but it’s in a positive way. A few years ago, he punched a huge hole in a clubhouse partition near his locker. These days, he rarely gets rattled. If things aren’t going his way, he returns to a simplistic plan.

“Just keep us in the game,” he explained. “I used to be like, ‘I gotta strike everybody out and I need to throw 100 miles per hour.’ It’s more now just doing what I need to give us a chance.”

Opposing hitters have seen a dramatic change in Sabathia too.

“He has become a pitcher,” Kansas City first baseman Mike Sweeney said. “Before this year everyone looked at him as a thrower. Before, he’d come at you in the first inning throwing 97 mph. Now, he’s working the corners.”

The way his dad taught him to.

Sabathia, who does everything right-handed but pitch and play golf, thinks of his father every day.

“All the time during baseball season,” he said. “He lived with me for my first three years in Cleveland. I just miss him in spring training, going fishing with him down there, things like that.”

Sabathia knows how proud his father would be of his upcoming All-Star appearance, the homecoming they’ll share.

“I know he’s watching,” he said.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.