Rhett gets a back story

- Share via

HIGHLAND COUNTY, Va. -- Donald McCaig has to make sure that the fences are mended so his sheep don’t stray, that his border collies are tucked away in a kennel, that his Pyrenees guard dogs are being looked after and that the leftover venison from supper has been disposed of before he leaves his beloved farm for a 30-day tour to promote “Rhett Butler’s People,” the new sort-of-a-sequel to “Gone With the Wind.”

Oh, and there’s one more chore: The driver’s side window in his 1989 Mercury station wagon -- his good car -- is broken. “If I can’t get it fixed in Staunton,” says McCaig, 67, “I’ll just cover it with plastic and duct tape and that will be that.”

Then McCaig will travel to Washington D.C., Atlanta, New York and other cities to speak to readers and sign copies of his book, which took six years to write.

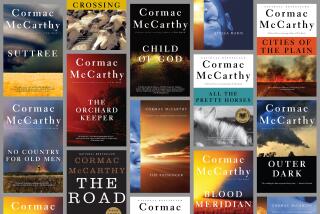

There already has been one official sequel to Margaret Mitchell’s phenomenal 1936 novel. Alexandra Ripley’s “Scarlett,” sanctioned by Mitchell’s estate in Atlanta, was published in 1991. And an unofficial version: Alice Randall’s “The Wind Done Gone” came out in 2001. Both books sold well but received harsh criticism.

The original novel, a colossal saga set in the Civil War-torn South, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937 and was made into the spectacular, all-time classic movie two years later. The book continues to sell well, so Mitchell’s estate agreed to let St. Martin’s Press -- which paid $4.5 million for the right to publish a sequel -- take another swipe at it.

For a while, it looked like Pat Conroy, who wrote a loving intro to an anniversary edition of Mitchell’s novel, was going to try his hand. But when that didn’t happen, St. Martin’s approached McCaig. He has written the historical novels “Jacob’s Ladder: A Story of Virginia During the War” and “Canaan: A Novel of the Reunited States After the War.” The Virginia Quarterly Review called “Jacob’s Ladder” the best Civil War novel ever written.

He has also written several books about sheepdogs, including the novels “Nop’s Trials” and “Nop’s Hope.” McCaig says he’s been able to “eke out a living” from the sales of all these volumes.

You know when you approach McCaig that you’re in the company of a real character. He’s got an earthy sense of humor and a laugh that sounds like a vintage tractor on a cold morning. He’s a barrel-chested man with a bushy white mustache and cumulus-cloud eyebrows. On this evening, he is wearing a yellow shirt, blue jeans, a white cowboy hat and green suspenders. A reddish dog whistle dangles around his neck. He looks like a color wheel.

Charlottesville, Va., writer Donovan Webster, author of “Aftermath: The Remnants of War,” has known McCaig for years. “Donald has original takes on everything,” Webster says.

Born in Butte, Mont., McCaig was lured to Manhattan as a young man. He worked for an advertising firm, including campaigns for Georg Jensen jewelry and After Six formalwear. Eventually, in the mid-1960s, McCaig decided he wanted to be a writer. He and his wife, Anne -- bitten by the back-to-the-land bug -- headed south in a pickup truck camper.

After consulting with poet and agrarian guru Wendell Berry, the McCaigs settled in this majestic, mountainous county in western Virginia, hard against the West Virginia state line. With 2,500 residents, Highland is one of the least-populated counties east of the Mississippi. “There are 150 people in our ZIP code,” he says.

In the 40 or so years they have lived here, the McCaigs have put down deep roots. McCaig is an elder at the nearby Williamsville Presbyterian Church, with a congregation of 12.

“Half of them believe in the rapture, and I believe in gay marriage, and everyone agrees to just not talk about those things,” he says.

While writing books over the years, he has also become a serious sheep farmer -- the McCaigs have 180 acres on the Cowpasture River -- and a top-notch dog trainer.

These days, the herd is small. A trio of collies -- June, Luke and Peg -- do the herding. “Peg,” he says, “is a dope.” A couple of guard dogs sleep with the sheep.

Throughout the year, McCaig enters his collies in field trials, competitions in which dogs herd sheep in various farm-like tasks. June, he says, was a semifinalist in a national contest in Gettysburg, Pa. He is hoping to take her to the world championships in Wales next year. But for now, he is on the road.

Early reviews of the new novel are mixed. Entertainment Weekly gave “Rhett Butler’s People” a C-plus. Stephen Carter, writing in the New York Times, called it a fine novel.

When McCaig received the offer, he was running his dogs in a trial on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. “That’s when I read ‘Gone With the Wind’ for the first time,” he says. “I decided I wasn’t interested in a conventional sequel.”

But there was something odd about Mitchell’s 1,000-page work: “Rhett Butler was constantly disappearing and reappearing, off doing work for somebody, making money somehow,” McCaig says. “I found a lot of holes in the story.”

He decided to write an overlay, a re-imagining that would patch up some of the holes. “I thought: I could do that.”

He met with the lawyers who oversee the Mitchell estate. “The only thing they said was that they were concerned about how I would handle slavery in the book,” McCaig says. “Some people have problems with Margaret Mitchell’s racial attitude.”

McCaig told them: “She was a Southern writer of her time. I am a Southern writer of my time.”

St. Martin’s offered him enough money, he says, to pay off his mortgage.

Rather than read the book again, McCaig worked from an outline. “Anne did a CliffsNotes synopsis of each chapter of the book,” he says.

He extrapolated from Mitchell’s text what Rhett Butler might have done or said. Mitchell may have had more of Butler’s back story in her unedited manuscript, he says. “She cut a quarter of her original novel.”

When asked if this will be the last official sequel, Paul Anderson Sr., an attorney for Mitchell’s estate, says, “I really think it is . . . but don’t hold me to that.”

There could well be a movie of “Rhett Butler’s People,” though McCaig says he has no interest in writing the screenplay.

Publishing success or no, McCaig plans on sticking with his dogs and working on the farm.

He points to a dry stone wall, which he calls his home-improvement “poverty project.”

“When I don’t have two dimes to rub together,” he says, “I can still work on that wall.”

He plans to keep flying under the radar. He has no Wikipedia page.

And he plans on staying in Highland County. He really likes the people.

Ethel Frampton, for instance, who helps around the house some. “She’s famous for her canned squirrel,” he says.

On the morning that he takes his car to the shop, he pulls over on the side of Highway 250. From a scenic overlook, Highland County is a country quilt of autumnal tones -- sycamore golds, oak browns, maple reds. McCaig says he knows he is home when he sees the landscape: “It brings a tear to my eye.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.