On Dani Shapiro and memoir in the age of social media

- Share via

Over at the New Yorker, Dani Shapiro meditates on memoir in the age of social media. “I’m a bit of an accidental memoirist,” she admits, describing her writing life. “I’ve written five novels and three memoirs. I never planned to write memoir at all … [b]ut we don’t choose the forms our work takes. We feel the pressure, wait for the explosion, then stand back, stunned and speechless at the shape that emerges.”

Shapiro — whose most recent book, “Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life,” came out last year — is absolutely right about that: The best and most honest books are those that catch us unaware.

Write what you know, beginning authors are often told, but in fact, it’s the opposite to which we should aspire. Writing, after all, is an art of the unknown, in which, as Shapiro points out, “I’ve sat still inside the swirling vortex of my own complicated history like a piece of old driftwood, battered by the sea. I’ve waited — sometimes patiently, sometimes in despair — for the story under pressure of concealment to reveal itself to me.”

She continues: “I’ve been doing this work long enough to know that our feelings — that vast range of fear, joy, grief, sorrow, rage, you name it — are incoherent in the immediacy of the moment. It is only with distance that we are able to turn our powers of observation on ourselves, thus fashioning stories in which we are characters. There is no immediate gratification in this.”

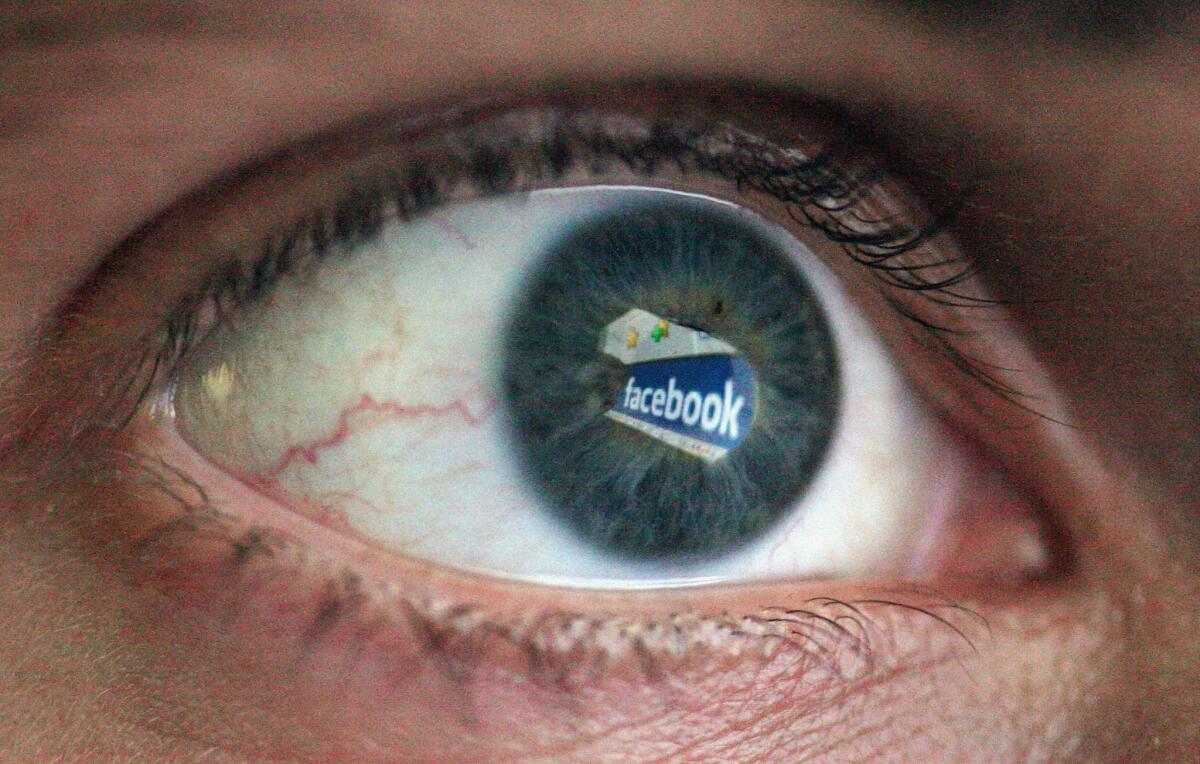

No immediate gratification: That’s it, exactly, what separates memoir from a Facebook post. For Shapiro, it’s the difference between depth and surface, between waiting, in silence, to discover what one is feeling and tossing off a quick status update that purports to tell us something without saying very much at all.

How, she wonders, do these impulses fit together? Is there a way to reconcile them at all? “My parents were in a car crash in 1986 that killed my father and badly injured my mother,” Shapiro writes. “If social media had been available to me at the time, would I have posted the news on Facebook? … And ten years later, would I have been compelled to write a memoir about that time in my life? Or would I have felt that I’d already told the story by posting it as my status update?”

On the one hand, that seems a false dichotomy: Why can’t it be both? But what Shapiro’s really asking is how, in an age of instant communication, instant reaction, do we find the space to let things incubate. She’s not the first writer to wonder this; five years ago, Rich Cohen raised a similar set of issues in an essay (which, full disclosure, I commissioned and edited) about the ways social media reconditions our relationship with the past.

For Cohen, literature relies on a certain distance, not so much from events as from the people we have left behind. How, he wonders, would Sherwood Anderson or Ernest Hemingway have written their early works if the people upon whom they based their characters could post complaints on their Facebook walls?

“A writer,” he notes, “should be judged by how honest and brutal he will be: by the quality of the secrets he tells, as well as by the panache with which he tells them. It’s what Czeslaw Milosz meant when he said, ‘When a writer is born into a family, that family is finished.’”

Writing, in other words, is an art of betrayal, and it’s hard to betray those with whom one remains in touch.

For Shapiro, that includes, perhaps most fundamentally, our own former selves, the ones who might have exposed all (and now do) in a stream of tweets and status updates, giving us the illusion that we have revealed ourselves when what we have exposed is really very little at all.

Yes, writers are always choosing their confessions; that’s in the nature of the art. But in much the same way as Shapiro (and also Cohen), I wonder at what point we begin to confuse “the small, sorry details — the ones that we post and read every day — for the work of memoir itself.”

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.