The David Cronenberg-Kafka connection

- Share via

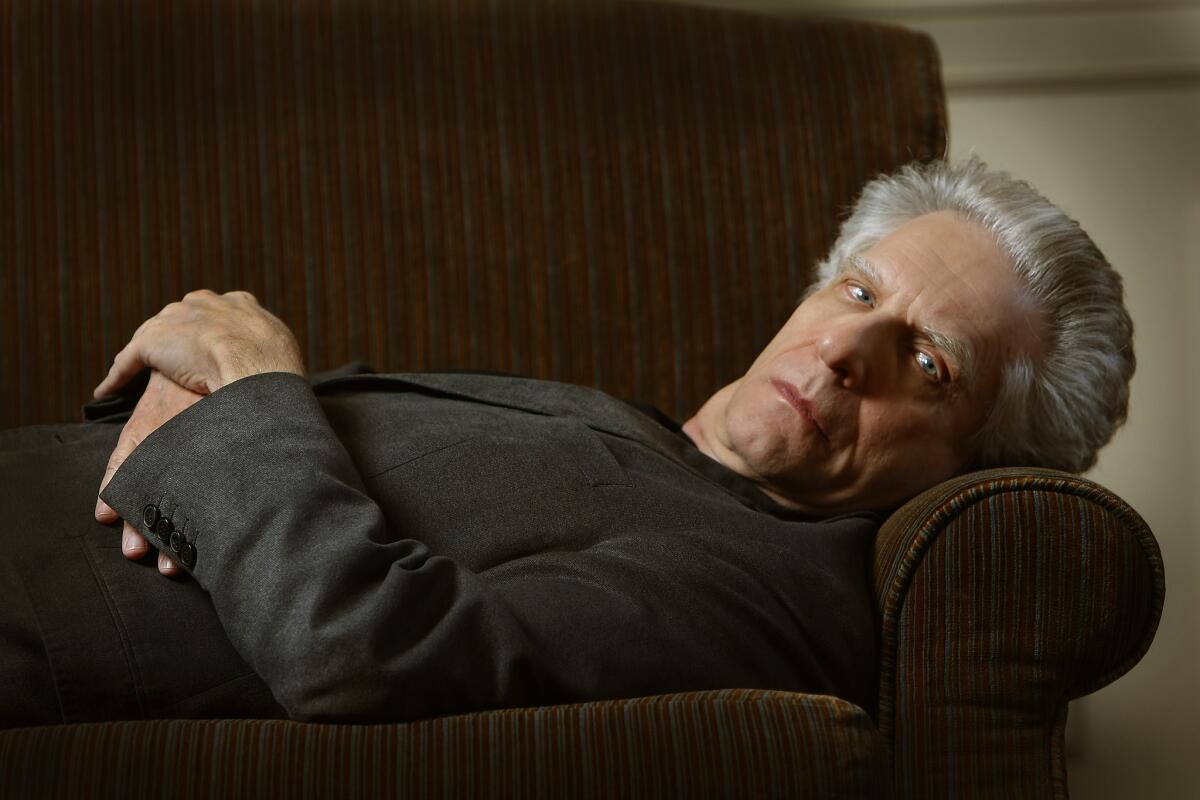

David Cronenberg begins his introduction to Susan Bernofsky’s new translation of “The Metamorphosis” by Franz Kafka (W.W. Norton: 126 pp., $10.95 paper) by raising an unexpected comparison: “I woke up one morning recently,” he writes, “to discover that I was a seventy-year-old man.”

The sentence echoes Kafka’s own first line, the greatest (I think) in all of literature: “When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into some sort of monstrous insect.” By turns specific and vague — what were those troubled dreams, Cronenberg wonders, and do they have anything to do with Gregor’s predicament? — it is an opening that destabilizes us from the outset, rendering the unnatural as natural.

Rendering the unnatural as natural is at the heart of Cronenberg’s work, as well; his films include “Scanners,” “Dead Ringers” and “Videodrome.” He is also a director with a strong literary bent, having adapted William S. Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” and J.G. Ballard’s “Crash,” as well as, more recently, Don DeLillo’s “Cosmopolis.”

Perhaps his most obvious connection to “The Metamorphosis,” however, is his 1986 remake of “The Fly,” in which a research scientist named Seth Brundle loses his humanity (both physically and spiritually) after inadvertently fusing himself with a housefly. Cronenberg cites the character in his introduction: “I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over, and the insect is awake.”

There are, of course, many fundamental differences between “The Fly” and “The Metamorphosis,” but the common thread is complicity. Both Brundle and Gregor are participants in their fates, albeit in very different ways. Brundle experiments on himself, and relishes his transformation, which makes him superhuman, or so he believes. Gregor, on the other hand, becomes a bug because he is a bug already, waking up in darkness to trudge to a job where he is not appreciated, working to support a family that fails to appreciate him, as well.

“Gregor has only himself to blame for the wretchedness of his situation,” Bernofsky writes in a cogent afterword, “since he has willingly accepted wretchedness as it was thrust on him.” The implications couldn’t be more clear. This is the genius of “The Metamorphosis,” indeed, of all of Kafka: that it is not the situation that condemns us but our response to it, that we are all always part of the problem, that the dehumanizing effect of modernity (which is, in the end, his great subject) is, cannot help but be, a two-way street.

Cronenberg understands this also; what is Brundle, after all, if not a metaphor for modernity and its discontents? And yet, in framing Gregor’s predicament through the filter of aging, he has turned the lens on the essential humanity of this character, who, in so many ways, is just like us, transformed by the degradations of daily existence until all that’s left is the bitter recognition that “to be human, a self-aware consciousness, is a dream that cannot last.”

ALSO:

Shelley Jackson’s winter’s tale

Why don’t iconic novels translate into film?

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.