Book review: ‘Panorama’

- Share via

Panorama

A Novel

H.G. Adler, translated from the German by Peter Filkins

Random House: 454 pp., $26

Life is short and art is long, as the saying goes, but the sad fact is that a work of literature may not outlive its human author. Such was the apparent fate of the work of H.G. Adler. He was forced to wait decades before several of his novels saw print, and two of them remain unpublished long after his death in 1988. But, remarkably, Adler has been rediscovered by American publishers and readers, and his 1948 novel “Panorama” is now available in an English translation.

Adler was born in Prague in 1910, and he survived the Nazi camps at Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Langenstein. He spent the rest of his life in London as a teacher, a journalist and the author of more than two dozen books of poetry, philosophy and history, including “Theresienstadt, 1941-45,” a monumental diary of his experiences.

Another novel by Adler, “The Journey,” is also now available in English, and both “The Journey” and “Panorama” are expertly and elegantly translated by Peter Filkins.

The central character of “Panorama” is named Josef Kramer, a name that was surely meant to evoke Josef K., the protagonist of Franz Kafka’s “The Trial.” Both authors are German-speaking Jews from Prague, and both characters are caught up in predicaments that are inexplicable and inescapable.

The title refers to an antique amusement that Josef visits during early childhood, a display of images that depict the “wonders of the world” — Vesuvius, Niagara Falls, the Great Pyramid. “Before the pictures change,” writes Adler, “the delicate strike of a little bell warns: ‘Attention, time’s up! Get ready for the next wonder!’” The spectacle makes a deep impression on young Josef and faintly augurs what destiny awaits him and the whole world, but not for the reason intended by the impresario.

“The otherwise familiar world has disappeared,” writes Adler. “…Thus the world you normally live in is turned off, and has in fact passed away. Another world is risen, which neither reading nor studying nor even dreams can manifest.”

The book consists of 10 long chapters, each one depicting an aspect of life in a world that “has in fact passed away,” that is, the highly civilized world of German and Austrian Jews before the Nazis came to power. Even child’s play, for example, can bring parental wrath: “Then Josef is among his toys and someone says, ‘Only street urchins drag their toys around like that!’” At boarding school, Josef endures a slur, but it has nothing to do with his Jewishness: “a pupil, who was only one class higher than Josef, called him a ‘Czech pig,’ because he was from Bohemia.” In that sense, “Panorama” is much more a novel of manners and a coming-of-age story than a work of Holocaust fiction.

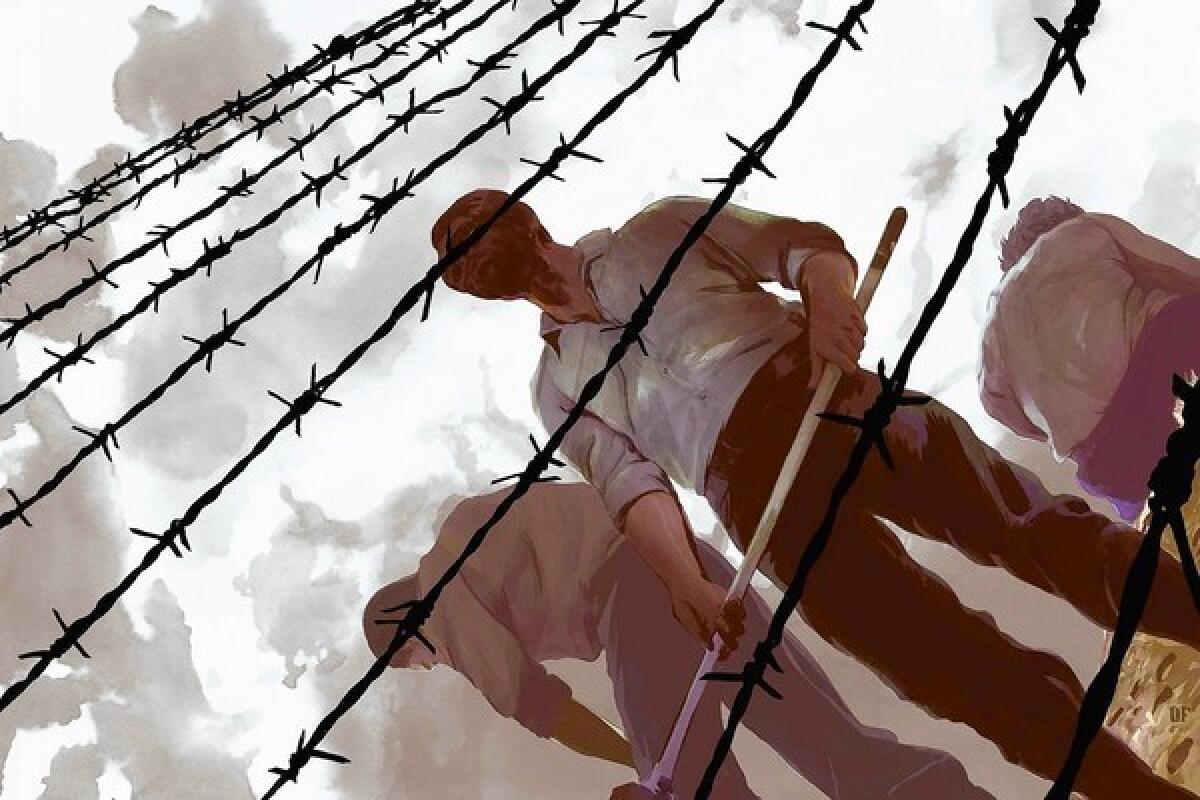

Yet the whole novel, so meticulous in its observations of home and school, family and friends, travel and adventure, is suffused with a terrible irony. “Perhaps one day better times will come which Josef will live to see,” writes the author of a moment when the young man’s sorrows seem modest enough. Josef goes on a camping trip with the fellow members of a hiking club — “Willi begins to tell ghost stories that he has made up on his own, such as the one about the old crone who lives in Landstein Castle and still wanders the countryside” — but a different kind of terror is visited upon him when he ends up behind the barbed wire of the Langenstein concentration camp.

Not until the end of Adler’s long and leisurely novel do we encounter the deadly peril that will overwhelm Josef and the rest of European Jewry and sweep away every other concern, every other aspiration. Only a single chapter, in fact, brings us face to face with the horrors of the Holocaust as Adler experienced them in real life, and even in English translation, the convoluted syntax of the original German text compels us to parse the words and phrases for sense and meaning.

“Langenstein is a deep hole of horror,” writes Adler, “human brotherhood barely traceable here, it being better that it not show itself before the ever-lurking malevolence, most of the collaborators being hardened young men who wildly and maliciously run the place with complete abandon, their better spirits not allowing them to remain cool-headed, even the decent collaborators needing to appear to succumb to the inhumanity of the place, as no one is able to escape such corruption.”

So “Panorama” can be a challenging book, and Adler himself offers it to the reader as an earnest effort to enter a mystery that is ultimately impenetrable. “[W]hen I was deported I said to myself, I won’t survive this,” he told a television interviewer in 1986. “But if I survive, then I will describe it ... and the fact that I have done so is not that important but is at least some justification for my having survived those years.” It’s hard to imagine a greater undertaking, moral or literary, by the author of a novel, and Adler has surely achieved what he set out to do.

Kirsch is the book editor of the Jewish Journal and author of, most recently, “The Grand Inquisitor’s Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.