Festival of Books’ diverse offerings

- Share via

Poets read to rapt audiences, and authors of fiction tried to explain the creative process. Celebrity chefs lured big crowds to sit under a hot sun, and mystery writers answered questions in SRO auditoriums. There was something for almost everyone at the 16th annual Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, held this past weekend on the USC campus. What follows is a sampling of reports on the festival from the Jacket Copy blog.

Meeting Ginsberg

Before she read a section from “Just Kids,” punk poetess Patti Smith set up the audience to laugh. “It has its beauty,” she said of her memoir, and “it has its sorrow.” But Smith said she would be reading something funny instead.

And it was, but there was a moment when Smith had to pause, a rush of sorrow greeting her from the page, making her voice waver. She took a breath and then carried on — for herself, for the packed audience in Bovard Auditorium at USC and for her love for the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who asked her to write the story of their friendship the day before he died in 1989.

Smith was not reading a passage about Mapplethorpe, but rather about the first time she met poet Allen Ginsberg in New York City. “Are you a girl?” Ginsberg asked, after spotting her a dime so she could get a sandwich.

The rapt audience, which had gathered Saturday to hear Smith and fellow memoirist Dave Eggers converse, roared with laughter.

Eggers and Smith are both artists who work in a variety of media — music, design, poetry and community-building — and they convey a sense that art is both a lofty ideal and a daily slog.

Smith said she felt blessed to have a calling to be an artist, while Eggers said he felt guilty. Hunched in what he called his “writing position” in his shed/studio, eking out a few hundred words a day, Eggers thinks about people who are “really working for a living.”

Where Eggers was often self-deprecating about his artistic gifts, Smith, mother to all the scrappy, anarchist souls, sought to soothe him and by extension everyone in the audience. “The emotional force of art is one of the things that’s kept me happy,” she said. “I’ve had hard times, lots of loss ... but I feel a calling to do this. It walks with me every day.”

— Margaret Wappler

Fact-check fun

Kicking off the Festival of Books’ banquet of panels at Bing Theater on Sunday, novelist Jonathan Lethem spoke about the occupational hazards that come with melding contemporary cultural references with richly drawn fiction.

In a reply to a question from moderator and Los Angeles Times staff writer Carolyn Kellogg on the Internet’s impact on readers’ investigation of his work, Lethem described the curious situation that resulted when the notoriously detailed fact-checkers from the New Yorker magazine called him with a concern about an excerpt from his 2009 novel, “Chronic City.”

Referencing made-up band Zeroville (which itself is a reference to Steve Erickson’s novel of the same name), the piece referred to the band’s having never played the iconic New York City punk club CBGB.

The fact-checker, citing a Zeroville record review available online, advised Lethem that Zeroville had in fact played CBGB. Of course, the review was written by Lethem and was just as fictional as the band in this case, but the novelist relished the idea of his fictional worlds colliding.

“In this case I don’t mind being wrong,” Lethem playfully replied to the fact-checker. “In my book they didn’t play CBGB, but I know they did, it’s OK.”

— Chris Barton

Matters of form

“Breaking Boundaries,” one of the first panels of the festival Saturday morning, featured four authors who flirt with the boundaries of form. Benjamin Hale, Olga Grushin, L.A. Times Book Prize-fiction finalist Frederick Reiken and Times Book Prize-fiction winner Jennifer Egan have not written traditional novels, if you can even call the books “novels” in the first place.

Tellingly, Hale’s book, “The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore,” narrated by a chimp “in love with humanity,” is probably the most conventional novel in the group. Based on true events, Grushin’s “The Line” tells the story of a Soviet family that waits in line for a year for tickets to see conductor Igor Stravinsky. Their alternating perspectives are interwoven with dreams in what Grushin calls a “universal fairy tale.”

Both Reiken and Egan describe their books — “Day for Night” and Pulitzer-prize winning “A Visit From the Goon Squad,” respectively — as linked story collections rather than novels. Egan didn’t even allow the word “novel” to appear on the hardcover edition of the book (though the word has since been added to the paperback).

Moderator Richard Rayner had each author read selections from their work and then opened the discussion posing the question: “Is it the job of fiction to explore its own form?” Egan pointed out that, throughout the history of the novel, writers such as Miguel de Cervantes and Laurence Sterne have played with form. Yet more than one author on the panel stressed that they did not set out to write something “formally interesting.”

Asked whether he thinks the times we live in influence form, Reiken said that though he’s obviously a product of our “fragmented but paradoxically connectible” culture, his use of form is not conscious but rather intuitive. His book was partly inspired by the story of 500 Jewish intellectuals killed during the Holocaust after being convinced they were to be hired as archivists. He imagined a scenario in which one or two of the men survived. The origin of Hale’s “epic bildungsroman” came as he sat in Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo surrounded by snow, reading and watching the monkeys. Grushin’s book, compared by one reviewer to “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” by Roald Dahl because of its magic ticket similarity, tried to answer the question, “What would make you stand in line for a year?”

The question of form, however, cannot be answered simply with a magic ticket. Egan probably summed it up best: Form should allow you to “do what needs to be done in the freest way possible.”

— Chris Daley

A priest called ‘G’

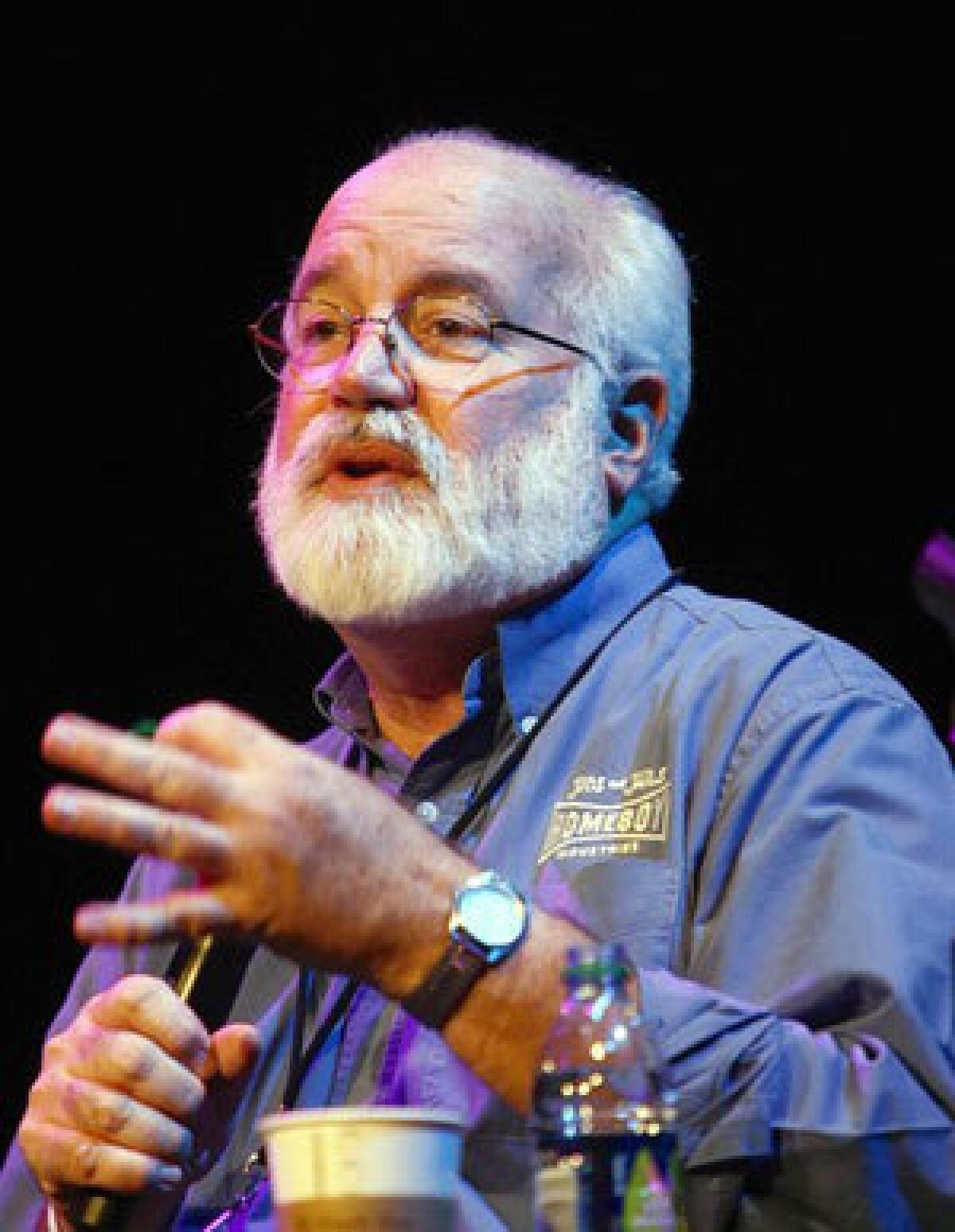

A roar of applause and cheers echoed through Bovard Auditorium as Times columnist Steve Lopez and Father Gregory Boyle took the stage Sunday. The 1,235-seat venue was nearly full, the audience eagerly waiting the compelling, compassionate and often hilarious stories of Boyle and his experiences assisting gang members.

“For some reason, it just doesn’t feel right calling you G-Dog,” Lopez joked as he introduced Boyle, who also goes by “G” or “G-Dog” among young members of his community.

A Jesuit priest, Boyle has spent the past 20 years running Homeboy Industries, an operation created to provide at-risk former gang members with counseling, education, tattoo removal and job training and placement in the hopes that they will become contributing members of the community. The idea is to offer a sense of hope and faith to these otherwise hopeless individuals. “If you give hope, the kid will stop planning his funeral and will start planning his future,” Boyle explained.

After visiting the site of Homeboy Industries a few days earlier, Lopez shared that he was simply blown away by the multitude and magnitude of tasks Boyle was expected to tackle within an hour, let alone within a day. “I was amazed by how many things this man could do at once. He has done this for decades and does it with such love and energy. He’s like a rock star there,” said Lopez.

Boyle, author of the bestselling memoir “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion,” attributes this energy to the fact that he is anchored by the delights and genuine joys of his duties. “Everyday it’s a privilege. Hilarity and heartache and intractable heartache after intractable heartache — I find the whole thing energizing,” Boyle said.

— Jasmine Elist

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.