Poet-think: ‘Is this too loud, too soft, am I going on too long?’

- Share via

When John Freeman, the editor of Granta, was setting up Sunday morning’s panel discussion on “The Art of the Poetic Line,” he related an anecdote about an exchange between Billy Collins, the former U.S. poet laureate, and Richard Ford, the novelist.

How come you novelists get all the credit and all the money, Collins supposedly asked Ford. “It’s really hard, Billy,” Ford replied. “You’ve got to write all the way to end of the page, and all the way down.”

Of course, the art of arranging poetic lines on a page -- complete with punctuation (or not), in metered or blank verse, interrupted by the pauses of white space -- poses hard choices of its own. That theme was enough to propel panelists Jill Bialosky, Matthew Dickman and Stephen Burt to dissect their craft, and demonstrate how it’s done by reading some of their own work.

FULL COVERAGE: FESTIVAL OF BOOKS

“When I’m writing poetry, it’s a very internal process, and there’s almost like a voice inside my head,” Bialosky said. “I follow the music of that voice. But with that said, I do pay attention to the line, and that often happens during the revision process.”

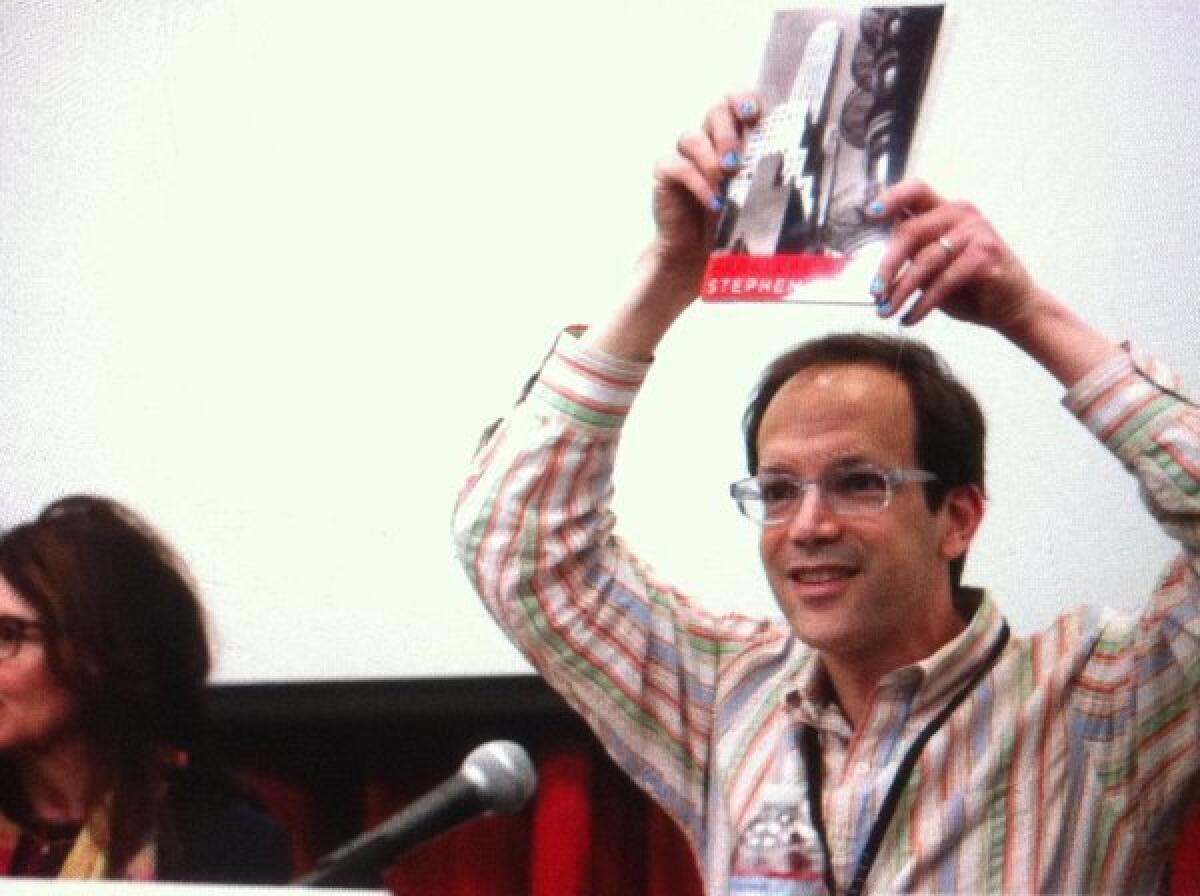

Picking up the theme, Burt, a Harvard instructor and Randall Jarrell devotee who sports colorful shirts, see-through eyeglass frames and blue nail polish, started talking into his microphone, then checked himself because he was projecting too loudly in the small, acoustically suspect USC lecture hall.

“That was an analogue in a way for what happens when one is revising a poem,” Burt said. “Is this too loud, is this too soft, am I going on too long? Does it need to stop more often to listen to itself? And one of the many things that a line break is, is a point where a poem stops to listen to itself and see whether it is going -- and if there are characters in the poem, see whether they are going in the right direction.”

INTERACTIVE: LITERARY L.A. MAP

Dickman said that when he first started writing poems seriously and “sending them to places like Granta and being rejected over and over again,” he wrote in a more constrained, self-conscious way, “like being on a leash,” thinking about “what the line was going to be, what the story was going to be, and all this other stuff.” Then, after going through a yearlong mental break, he tossed out most of the rules and “started writing a different kind of poem.”

“I just wanted to write something that felt energetic to me and that I wanted to read,” he said. Later, Dickman told the room that what he admired about poets such as Frank O’Hara, to whom he has been compared, was a sense of poetry that’s based on “an idea of freedom and not being precious.”

In response to an audience member’s question about the first poem the panel members ever wrote, Bialosky said she couldn’t remember her own first verses, but she remembers the first poem she ever heard: Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Swing.”

“In that poem, the line imitates the music of the poem. And I remember when I was little, going on the swings, and reciting the poem in my head,” Bialosky recalled.

How do you like to go up in a swing,

Up in the air so blue?

Oh, I do think it the pleasantest thing

Ever a child can do!

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.