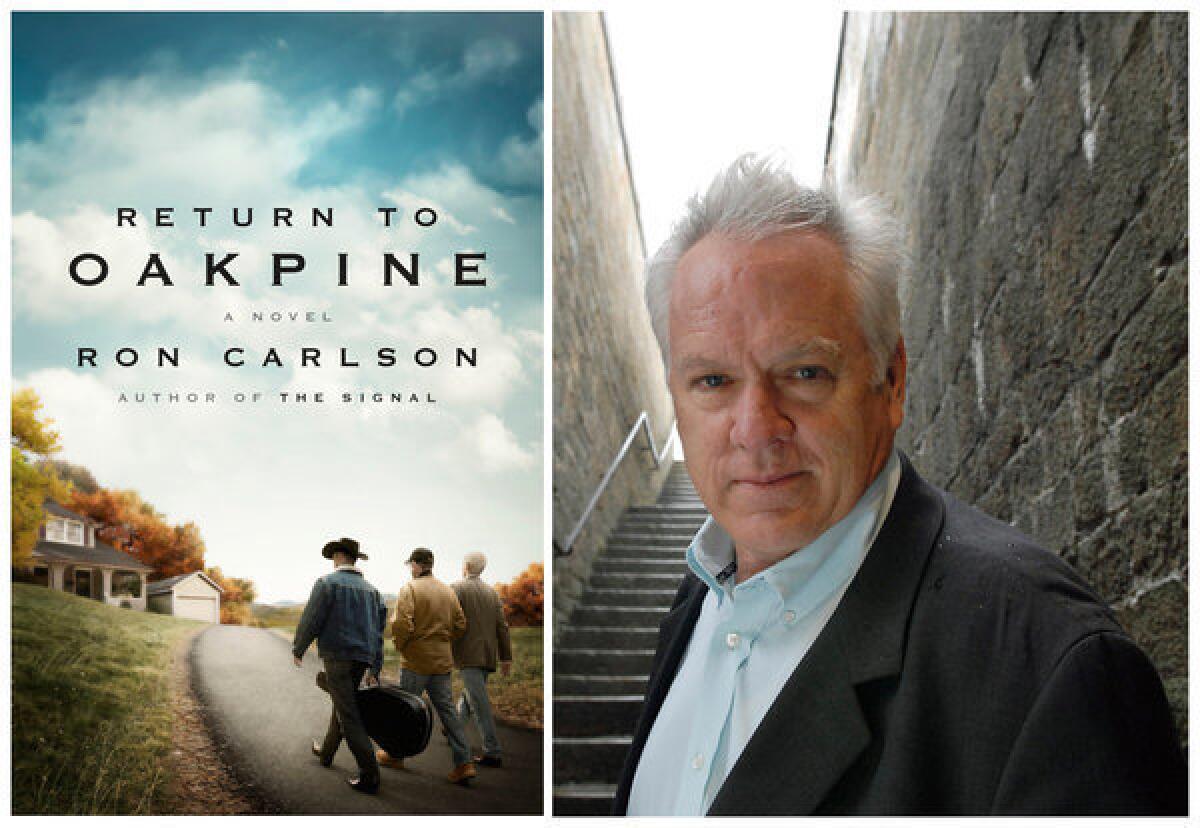

In Ron Carlson’s new novel, old pals return — and so do old hurts

- Share via

Ron Carlson hadn’t published a novel in more than a quarter-century when he put out the exquisite “Five Skies” in 2007. It’s not that he wasn’t working; during that period, he wrote five story collections and a work of YA fiction; he also ran the creative writing program at Arizona State University before taking an equivalent position at UC Irvine in 2006.

“I don’t feel like there’s been any time between anything,” he told The Times after “Five Skies” appeared. “I just fell so deeply in love with the short story. Finally, I had the material I needed to get the novel right.” That says a lot about Carlson’s approach to fiction, which is to let ideas and situations percolate, and in so doing to articulate with care and nuance the inner lives of characters who themselves may not be emotionally articulate: men mostly, middle-aged, living in the rural west and wrestling with the sense that opportunity has passed them by.

Such is the case with “Return to Oakpine,” which revolves around a group of high school friends 30 years after graduation, in the small Wyoming town where they were raised. The novel begins with a simple errand: A man named Craig Ralston is called upon to refurbish a garage apartment for his old compatriot Jimmy Brand, who is coming home to die.

The year is 1999, and Jimmy is nearing 50, a writer who left home after high school in the wake of a family tragedy. That Carlson doesn’t reveal all this immediately is part of his method: to let us get situated in the narrative, to meet the various players, to see how much and how little the town has changed.

“It had been raining now for a little while,” he writes, “and the water sheeted and merged as it ran down the windshield. It blurred the scene before him, the people across the football field in their coats, dots or red, brown, yellow, green, blue, three hundred people in the rain of Wyoming. They would blur and focus in the glass.”

At the heart of such an image is the idea that we never escape the past, not even a little bit of it, that it becomes a lens, a filter, through which to measure ourselves. In a town such as Oakpine, this can’t help but bleed into the present, reminding us of old hurts, old longings, of who we were and who we never will become.

Early in the book, after removing a long neglected boat from the garage, Craig encounters Jimmy’s father, who takes in the scene before him without a word. “There are a thousand things, a thousand stories, and their parts that never get said,” Craig thinks. “It’s just a boat and just a garage, but they’ve choked him all this time. I’m no better. Words don’t weigh an ounce, and I can’t haul them.”

Here, Carlson uses the particulars, these physical details, to get at the emotional material underneath. Jimmy’s father hasn’t spoken to his son in 30 years, partly because of that family tragedy (a boating accident in which another son, Matt, was killed) and partly because of his inability to deal with Jimmy’s homosexuality.

A similar sense of isolation afflicts nearly everyone in the book. There is Craig, stuck in the family hardware business, “[a]ny satisfaction he’d gotten out of finding someone the right hex nut … ghosted, gone.” There’s his wife, Marci, engaged in a flirtation with her boss at the local art museum, which threatens her relationship with Craig like a ticking bomb. There’s Mason, another old friend, “choking on his sublime unhappiness” as a lawyer for whom “[t]he mathematics of everything had grown murky and was now impossible.” And then, of course, there’s Jimmy, stricken with AIDS and looking for a way to make his last months meaningful, looking for a way to belong.

To highlight that, Carlson introduces music as a connective fiber; Jimmy, Craig, Mason and a fourth man, Frank (who now owns a local bar and brewery) had a band back in school. Now that they are all in town, the band reunites, after a fashion, with Craig’s 17-year-old son Larry chiming in on guitar.

Lest this sound reductive, Carlson is too sharp, too subtle, to invest too much in it: Music is not going to save anyone, not in this life or in any other. He makes the point explicit in a flashback to a high school party where the band, at long last, hits its stride. “This is real,” Jimmy exclaims. “This is the best” — only to realize, in the next instant, that “[w]e only have a year of this.” Even at the moment of their most profound connection, the dissolution has begun.

On the one hand, that’s because Jimmy knows he’ll be leaving; in the late 1960s, in a small town in Wyoming, there is no place for him. But even more, it’s because what is true for them is true for everyone, that circumstances get the better of us, that life will always intercede. “I thought, I guess,” says Frank, looking back, “that we’d just be a band for a few years, something. But, we go to the reservoir, Matt drowns, and everybody vanishes. It was like time broke in two, and then we’ve had the rest.”

There’s a taciturn beauty to such a statement, with its sense of displacement and acceptance at once. This, too, is what Carlson wants to show us: that if his characters can find a way to see things clearly, they might achieve if not redemption then a kind of grace. “It was so close to being enough,” he writes of Marci. “She was in some kind of weird era. She recognized that if she stood still, she’d sink.” Still, Marci — like everyone here — remains aware of her commitments, of exactly what’s at stake.

This is the tension that drives “Return to Oakpine,” between what we want to do and what we need to do, between our dreams and our responsibilities. Or, as Carlson observes late in this elegant and moving novel, “There was a vague lump in his throat … that he had thought was excitement but now felt like an urgent sadness; actually it felt like both.”

Return to Oakpine

A Novel

Ron Carlson

Viking: 264 pp., $25.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.