In ‘Dockwood,’ a geography of tiny images

- Share via

Jon McNaught’s “Dockwood” (Nobrow Press: unpaged, $19.95) is one of those books you could easily overlook. Gathering two short stories in comics form, it came out in England a year ago, but although McNaught won the Prix Révélation (for best newcomer) at the 2013 Angouleme International Comics Festival — an award previously won by Daniel Clowes, Art Spiegelman and Will Eisner — he’s gotten no attention in the United States.

Partly, that has to do with the British comics scene, which has had its issues crossing over, and partly with McNaught’s publisher, which until recently was not particularly active here. But either way, “Dockwood” is worth your attention, a terrific rendering of life in desolate suburbia: autumnal (it takes place in fall), understated, moving, deft. At its center are the sorts of lives Raymond Carver made a career representing: a man who works at a retirement home, two boys with a paper route.

The style is similar to that of Chris Ware (who, not coincidentally, blurbs the book) — small images, in some cases as many as 28 per page, and very little dialogue. This is visual storytelling at its purest, minimalist and evocative, asking us to make connections, to participate in bringing the narrative to life.

It works because McNaught is not a sentimentalist. His town, Dockwood, is marked by the most familiar signposts: a bus advertising a Dwayne Johnson movie, a “South Park” poster in a boy’s room. Pop culture is the common vernacular, both for the residents of the senior center, for whom television is a constant companion, and for the kids, who come to full expression only in the throes of a video game.

We are disconnected, these stories mean to tell us, and yet the miracle is that we still find a way to come together, whether in the offhand kindnesses (a cup of tea, an extra egg) we extend to others or in our restless efforts to belong.

What’s striking is how recognizable all this is: Dockwood may be an English suburbia, but it’s a universal one as well. The implication is that we now occupy a global landscape in which the boundaries have blurred (pop culture again) as the distinctions of place and country have grown thin.

On the one hand, this suggests a flattening: What does it mean that Dockwood could be anywhere? Yet on the other, it brings us to a curious (and unexpected) confluence, in which our most essential similarity may be our loneliness and isolation, and our redemption, such as it is, comes from the smallest gestures, which are all we have to offer in a homogenized world.

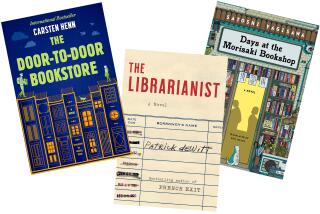

ALSO:

Ansel Adams and the art of framing

Imagining Jorge Luis Borges’ ‘Library of Babel’

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.