Measure HLA pits safety advocates against firefighters

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Wednesday, Feb. 28. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- L.A.’s roadway reckoning pits safety advocates against firefighters

- Your guide to the California Senate candidates’ views of housing and homelessness

- This energetic dance party hides in a tiny L.A. bar

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Battle lines drawn in L.A.’s street mobility ballot measure

Los Angeles voters are facing a roadway reckoning of sorts on the March 5 ballot. Will those who live in the capital of car culture commit to giving up a portion of city streets to cyclists and pedestrians in the name of public safety?

At its core, Measure HLA would require the city to add safety upgrades to certain streets when it repaves or modifies as little as an eighth of a mile of those roadways. The upgrades would expand and connect L.A.’s bike lanes, build dedicated bus lanes and nicer public transit stations. Pedestrians, especially near schools and parks, would be better protected by raised crosswalks, curb extensions and other safety features.

The tradeoff: fewer traffic lanes or parking, depending on the location.

The measure’s proponents point to alarming levels of carnage on L.A. streets. In 2023, 336 people died in crashes and more than half of them, 179, were pedestrians. That’s the highest number since the city started keeping statistics more than two decades ago.

But despite adopting a bold plan in 2015 aimed at improving roadway safety — while making the city easier for pedestrians and those on bikes and on transit — the city has barely followed its own guidelines.

A coalition of community groups, environmental organizations, labor unions and some of L.A.’s elected officials have voiced their support for the citizen-drafted measure, which would force the city to make good on its street safety blueprint.

The union representing L.A.’s firefighters recently came out against the ballot measure, saying the plan would create more gridlock and hinder their ability to get to emergency scenes quickly.

A new ballot measure for an old city plan

Here’s some background. In 2015, the L.A. City Council adopted Mobility Plan 2035, which aimed to “set the stage for the way we move in the future.”

The intention was that by making streets safer and more “livable,” more people would forgo driving, which would reduce congestion and improve our horrible air quality. The plan would be a notable shift after roughly a century of engineering decisions that put the speedy movement of motor vehicles above all other concerns.

However, the 20-year mobility plan has mostly been an aspirational guide — only about 5% of it has been implemented. Meanwhile, traffic deaths continue to climb.

When Mobility Plan 2035 was adopted in 2015, 88 pedestrians were killed by drivers. Last year, that annual figure more than doubled. Looking at the last eight years, more than 1,100 pedestrians were killed. Pedestrians make up more than half of the roughly 2,180 people who were killed in crashes on L.A. streets between 2015 and 2023.

Studies have shown that features including protected bike lanes, enhanced crosswalks and narrower vehicle lanes help reduce vehicle speeds, a leading factor in deadly crashes.

In 2022, a coalition of community members and safety advocates said enough was enough. A successful petition drive put the issue to lawmakers. The City Council punted to voters, who will decide whether Mobility Plan 2035 should become law.

Why are firefighters opposed to the measure?

Representatives from the LAFD union say the plan would hinder their ability to get to emergency scenes as quickly as possible. They also say designs aimed at making streets safer create more danger and chaos.

“We need to make our streets safer, but HLA is not the way,” UFLAC President Freddy Escobar told me via email.

Escobar believes that Measure HLA represents a false promise of safety and says fire officials need to be consulted before streets are changed — a provision already embedded in the plan.

The mobility plan’s final environmental impact report said that as L.A. grows, the roadway changes “would increase congestion, which could impede emergency access.” But the report also states that many redesigns would feature center left turn lanes, which emergency vehicles could use to bypass car traffic.

Additionally, the city has been equipping some emergency vehicles with transponders that give LAFD vehicles green lights along their route, a program that could be expanded. And emergency vehicles are allowed to use bus-only lanes.

Escobar took issue with those who say response times could be improved, saying they’ve “never had to ride in an ambulance or firetruck in an emergency when every second can mean the difference between life and death.”

What do we actually know about response times and street infrastructure?

It’s important to note that LAFD response times citywide have been increasing for several years. Escobar pointed to an increase in emergency call volume that hasn’t been matched with more firefighters and vehicles.

But when it comes to data-based research, the suggestion that slower emergency response times are linked to street reconfigurations that remove lanes — a so-called road diet — “doesn’t really hold much water,” said Wes Marshall, professor of civil engineering at University of Colorado, Denver.

Marshall wrote “Killed by a Traffic Engineer,” set to be released in June, which challenges long-held assumptions about street design as traffic violence surges. He believes firefighters “are coming at this from a good place” and their arguments seem logical, but transportation in practice can be “counterintuitive.”

Marshall co-wrote a study, published June 2019 in the Journal of Transport & Health, which analyzed 12 major U.S. cities to better understand how bike lanes affect safety.

“Protected and separated bikeways weren’t just making cities safer for the bicyclists, it was making it safer for all modes of transportation,” he explained. By slowing down car traffic on narrower streets, drivers “can often get through the network just as fast. But they’re doing it at a slower speed as opposed to going 50 miles an hour and then stopping for two minutes.”

Road diets “do not degrade response times for law enforcement and emergency services,” according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, which noted they can in fact improve response times.

Michael Schneider, founder of mobility advocacy group Streets For All and an organizer for the Healthy Streets LA initiative, said the union’s reaction to Measure HLA is “very myopic,” focusing too much on response time “over the safety of people they are responding to.”

“There’s always flexibility,” Schneider said. “The city can both implement the mobility plan and ensure that emergency services are maintained. We don’t have to choose.”

Today’s top stories

Politics

- Your guide to the California Senate candidates’ views of housing and homelessness.

- California’s Julie Su is up for Labor secretary confirmation again.

Crime and courts

- Diddy’s ‘Love’ producer Lil Rod accuses him and associates of sexual assault and illicit behavior.

- ‘Road House’ brawl: Amazon used AI to replicate actors’ voices during strike, a lawsuit alleges.

- Representing yourself in court? L.A. Law Library can help you prepare.

- A teen was beaten and stabbed by a group at Dockweiler Beach; mom says suspects yelled homophobic and racist slurs.

- LAPD officers fired over COVID vaccine dispute won’t get their jobs back, a judge rules.

- California seized enough fentanyl last year to kill everyone in the world ‘nearly twice over.’

Climate and environment

- From Mammoth to Tahoe, a powerful blizzard could sock the Sierra with up to 12 feet of snow.

- California libraries may lose free passes to state parks as budget deficit mounts.

More big stories

- With state approval, Rancho Palos Verdes to fast-track landslide mitigation.

- Sewage could be California’s next tool in fighting the opioid epidemic.

- A county watchdog report urges disbanding sheriff’s ‘aggressive’ Risk Management Bureau.

- Shohei Ohtani is making his Dodgers spring debut as the team’s new No. 2 hitter.

- A tent encampment rises outside Ojai’s stately City Hall. Its residents might break your heart.

- San Francisco’s iconic Union Square Macy’s will close.

- Undocumented immigrants in California could have a new path to homeownership.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Editorial: Florida shows how to bungle a measles outbreak.

- Robin Abcarian: What exactly did ‘SNL’ prove by inviting Shane Gillis back as host?

- Helene Elliott: Thank you, readers, for helping my sportswriting dream come true.

- Patt Morrison: Take a walk through L.A.’s spectacular, neglected and paved-over cemeteries.

- Sammy Roth: Electric vehicle sales slowing down? Don’t panic.

- Michael Hiltzik: As measles spreads, ‘herd stupidity’ grips Florida’s government.

- Bill Plaschke: Ohhhhtani! The newest Dodgers star homers in gasping good debut.

- Gustavo Arellano: The rise and stumbles of the San Fernando Valley Latino political machine.

- Mary McNamara: We never dealt with the trauma of 2020. Now it’s created an even bigger crisis.

Today’s great reads

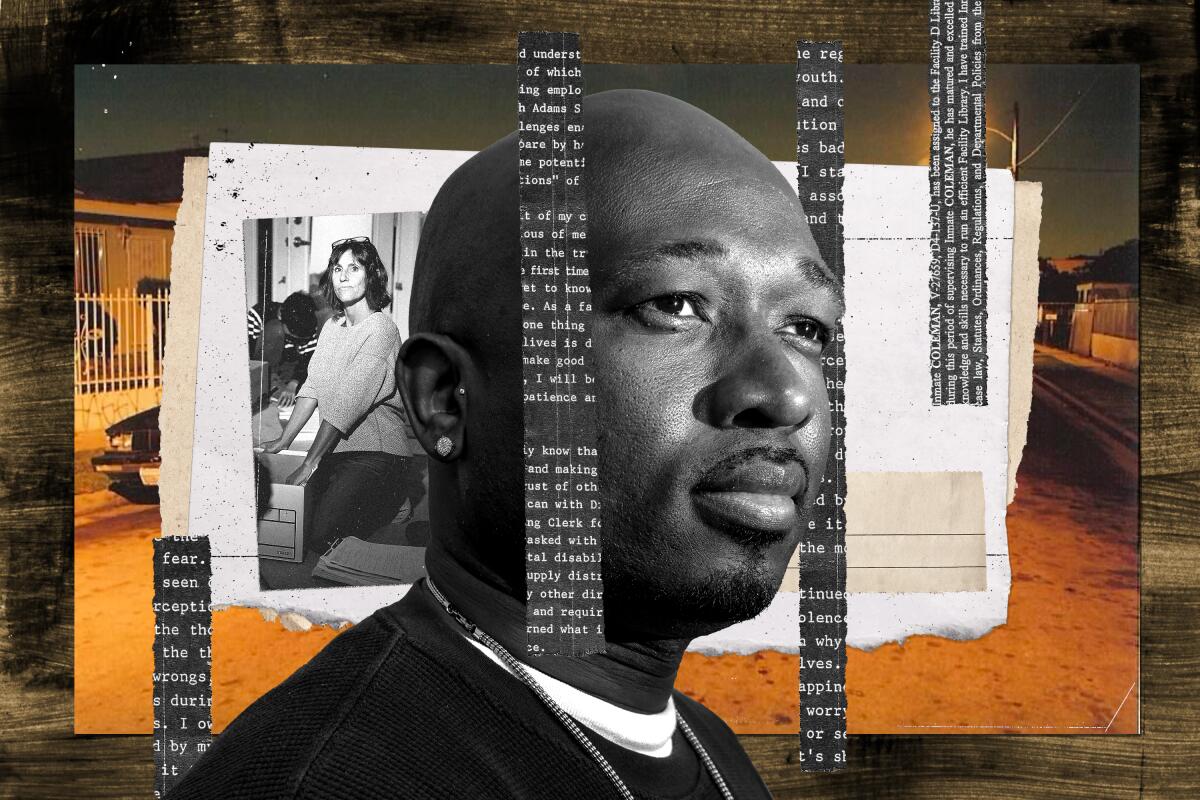

He’s wrongly convicted. She’s a hippie mom from Topanga. Can they prove his innocence? It seems impossible to analyze Jessica Dirschel’s success without considering race and class. If she weren’t an educated, middle-aged white lady from west of the 405, would Jofama Coleman’s murder conviction have been overturned?

Other great reads

- Closer to China than to the Japanese mainland, these idyllic islands confront the prospect of war.

- Being in community is a choice. And these L.A. artists keep picking each other.

- ‘You’re staying overnight?’ Inspire envy as you slumber in this otherworldly treehouse hotel.

- Orange County loves love and wants couples who are looking to take the matrimonial leap to stop by the courthouse Thursday — leap day, that special date that only arrives once every four years.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 🥳 This energetic dance party hides in a tiny L.A. bar — no cover, no line, no RSVPs.

- 🎭 A Bay Area play posits the dangers of tech. The playwright wants its makers to see it

- 🎤 Bob Dylan joins Willie Nelson’s Outlaw Festival tour bound for the Hollywood Bowl in July.

Staying in

- 📖 ‘Today’ co-anchor Savannah Guthrie puts her faith on the line in a new book.

- 🧑🍳 Here’s a recipe for turkey tostada with chipotle sauce.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... a great photo

Show us your favorite place in California! We’re running low on submissions. Send us photos that scream California and we may feature them in an edition of Essential California.

Today’s great photo is from Times contributor Stephen Schauer. Under the canopy of an enormous olive tree sits the remodeled, modern addition for a family of four that connects them to the Ivanhoe Reservoir in Silver Lake.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Stephanie Chavez, deputy metro editor

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Editor’s note: The Feb. 27 edition of Essential California stated that Sade Elhawary, Efren Martinez and Dulce Vasquez are seeking a seat on the Los Angeles City Council. They are actually running to represent state Assembly District 57.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.