For Mexicans in the U.S., the president of their homeland makes for spirited debate and begrudging silence

- Share via

Half of the De La Vega family migrated to San Diego from Mexico City over 25 years ago. Distance alone could never drive them apart.

Each year they met in the United States or in Mexico to celebrate birthdays, weddings, baptisms, Thanksgivings and Christmases.

Family harmony, however, was altered the moment Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidency of Mexico.

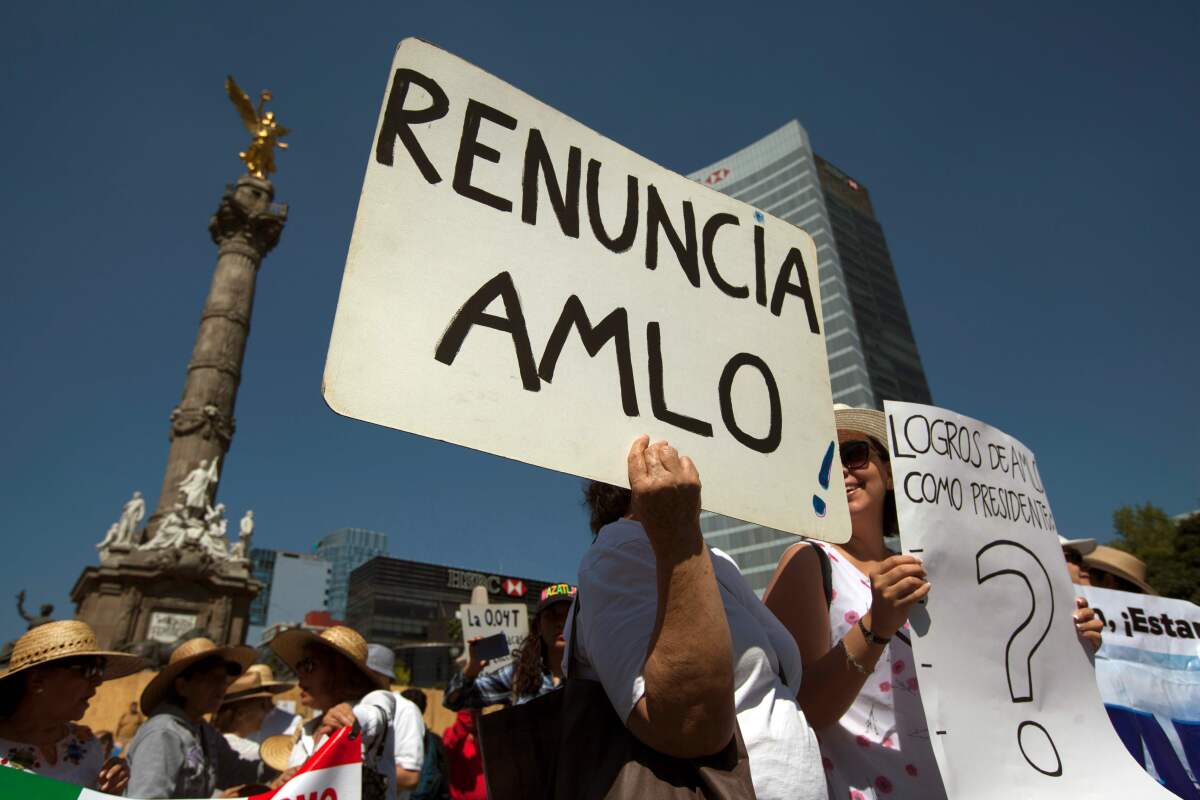

Considered to be a left-wing populist politician, AMLO, as he is known in Mexican political circles, overwhelmingly won last July’s election after two failed attempts.

“We used to talk about anything, religion, politics, whatever it was, and although there were opposing views, nobody got angry,” said Blanca Susana De La Vega from her home in Bonita. “Now the family is completely divided, and some have even stopped talking to each other.”

It is a familiar enough tale in the U.S., where some family relationships have undergone a kind of cold war following the victory of President Trump. But for Mexicans living in this country, the election of López Obrador has unleashed tensions and awkwardness across two countries facing a set of challenges from drug-related violence to polarized politics. While the older De La Vegas tend to praise the Mexican president, the youngest and frequently more prosperous family members reject him.

To be of Mexican descent in the U.S. — whether one born in that country or as an American who traces his or her roots to Mexico — is to have an intimate and complicated relationship with our southern neighbor. Because so many travel between the countries, what happens in Mexico resonates deeply with Mexican Americans and Mexicans living in the U.S., who frequently send money to family in Mexico. Even for Mexicans who have lived in the U.S. for decades, Mexico is typically a source of love and pride, frustration and heartache.

The disagreement over Lopez Obrador in part underscores the conflict in Mexico — and by extension wherever large numbers of expatriate Mexicans live — between the so-called “Chairos” and “Fifís.” It is an old conflict steeped in prejudices based on class and skin color.

“Chairo is the defender of the so-called Fourth Transformation” — the name that AMLO has given to the political movement that he leads — “who, regardless of the mistakes or blunders his leader may commit, will justify each and every one, with any type of pretexts,” said journalist Hugo García Michel.

The Chairo is associated with being poorer or more working class — and darker-skinned. From the days of the dictator Porfirio Díaz, Fifí has been used to describe more affluent — and lighter-skinned — Mexicans who tend to occupy the pedestals of Mexican society and government.

“The supposedly aristocratic people of the country were called that way, until AMLO began to use the word to attack his adversaries, whom he characterized uniformly as conservatives, rightists, reactionaries, with high purchasing power and white skin,” Garcia Michel said.

Although she never considered herself an activist, De La Vega got personally involved in politics during Mexico’s elections, when she traveled from Southern California to the Mexican capital to make sure her family members went out to vote.

“My older aunts wanted to vote, and I thought it was important that they went to the polls, because at that time any vote counted,” she said.

The Chairos and Fifís faced off on social media, and De La Vega said her family and friends were no exception.

“We had a group on WhatsApp, but some were so upset that they have left the group and stopped talking to us,” she said.

On the first day of September, a group of Angelenos met in the offices of “Vamos Unidos USA,” an organization that sympathizes with the National Renewal Movement headed by López Obrador. They were there to watch his State of the Union Address online.

The group of about 10 people acted like old acquaintances, greeting each other and drinking coffee served with a traditional Mexican pan dulce.

When López Obrador referred to migrants in the U.S., Juan José Gutiérrez, director of the Full Rights Coalition for Immigrants in Los Angeles applauded.

“They should be accountable and tell us what happened to the 1 billion pesos that ex-President Peña Nieto gave to the 50 consulates for the defense and legal protection of Mexicans facing deportation,” he said. “We want accountability.”

The Mexican president also condemned the Aug. 3 mass shooting in El Paso, which investigators said was committed by a gunman determined to kill Mexicans. Eight Mexican nationals were killed and six injured.

“We once again express our condolences to the families of the victims of the mass murder in El Paso, Texas.” Lopez Obrador said in his address. “We reiterate our condemnation of this hate crime motivated by racism and xenophobia.”

Ramón Gómez, 71, originally from the state of Sonora, said he appreciated the words of support from the president, but wanted him to do more about his homeland’s persistent corruption and social inequality, which drives many to flee.

“The president has also said that migrants are important to the country, but he has to do something so that they don’t mistreat us so much here,” Gomez said.

Ricardo Pérez, a civil lawyer born in the Mexican state of Nayarit, has lived in the U.S. for all but four of his 37 years. He listened to the speech with his family. He supported programs under Lopez Obrador’s administration designed to help young and old Mexicans, which many consider populist and that in some corners of the U.S. might be decried as socialist.

“Although they receive little money from the government, the goal is to mitigate the poverty of millions of people,” Perez said.

With family members on both sides of the border, Pérez says he would like to have heard López Obrador talk more about migrants in the U.S at a time when they face not only harsh political rhetoric from the highest level of government but also discrimination and violence.

“I wish that in these nine months as president he had come to the United States and spoken louder in favor of the rights of Mexicans in the United States, especially the undocumented,” Perez said.

A Pomona resident, Javier Motilla migrated to the United States 20 years ago from the state of San Luis Potosí. To him, López Obrador has failed to stem the growing tide of bloodshed that has washed over Mexico, where murders, kidnappings and femicides seem to be climbing and the country appears to be returning to the violent nadir of the drug wars. Many Mexicans who have legal status, or have become American citizens, and their U.S.-born children and grandchildren frequently return to Mexico and confront the shaky security in many parts of the country.

Still, Motilla adds that it’s perhaps too early to judge the president’s administration.

Max Aub is much less optimistic. A television host and 18-year resident of the United States, Aub said López Obrador’s words and the reality on the ground are very different.

“I think that AMLO has scored some points fighting against corruption, but that’s all,” he said. “There is nothing to be happy about, and instead there are many things that cause great concern. ”

Aub is especially pessimistic about Mexico’s economy.

“The promise was a 6% growth, but in reality there is a very serious economic stagnation,” he said.

Originally from Mexico City, Aub said he feels López Obrador is performing so badly that there will be an inevitable crisis leading to serious change.

But it is the escalating violence in Mexico that many of those in the U.S. who watched the president’s State of the Union found most concerning. Organized crime and cartel violence have claimed about 35,000 lives in the past year — about 8,000 more than in 2011, when former President Felipe Calderón declared war on drug cartels. Another 40,000 Mexicans have been reported missing in recent decades.

“Violence and crime should be AMLO’s next priority,” said Moisés Rendón, who hails from the town of Poncitlan in the Mexican state of Jalisco. “But the consciousness of working for peace must be imposed in the minds of all Mexicans.”

Like many of his compatriots, Juan José Gutiérrez stood at attention, saluted the Mexican flag and sang the national anthem before López Obrador’s speech. However divided Mexicans are over their president, he suggested, they will unite on Monday around the national aspirations expressed by Independence Day.

“We are here because we love Mexico, because we want a better country where people do not have to leave out of necessity. We want to celebrate this Sept. 16 knowing that our country is on the right track.”

Special correspondent Jorge Macías contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.