Column: In scandal over LAPD officers falsely tagging people as gang members, video confirms an old suspicion

- Share via

I wish that I were shocked, or even surprised, by the news that almost two dozen LAPD officers are being investigated for allegedly falsifying reports to arbitrarily label people as gang members.

That’s a complaint I’ve heard for decades from young black men who’ve grown accustomed to being randomly interrogated by police in South Los Angeles and added to an official gang member database based on little more than their nicknames or the logos on their baseball caps.

Their protests to authorities went nowhere. After all, who are you going to believe — the clean-cut cop with the badge and the authority, or the tatted-up teen wearing “gang colors” and saggy jeans?

Now body-worn cameras are giving those complaints new legitimacy.

When a San Fernando Valley mother insisted last year that her teenage son was wrongly labeled a gang member, a look at the body cam footage confirmed that the officer’s report didn’t match what the camera caught.

Her son was exonerated, and an investigation was launched. Now 20 officers from the Los Angeles Police Department’s elite Metro squad have been ordered to stay home or assigned to desk jobs while the department examines discrepancies in their field reports.

And LAPD Chief Michel Moore has pledged to keep widening the net until he figures out how widespread this is, what might motivate officers to cheat and what it will take to restore the community’s often fragile sense of faith in the police.

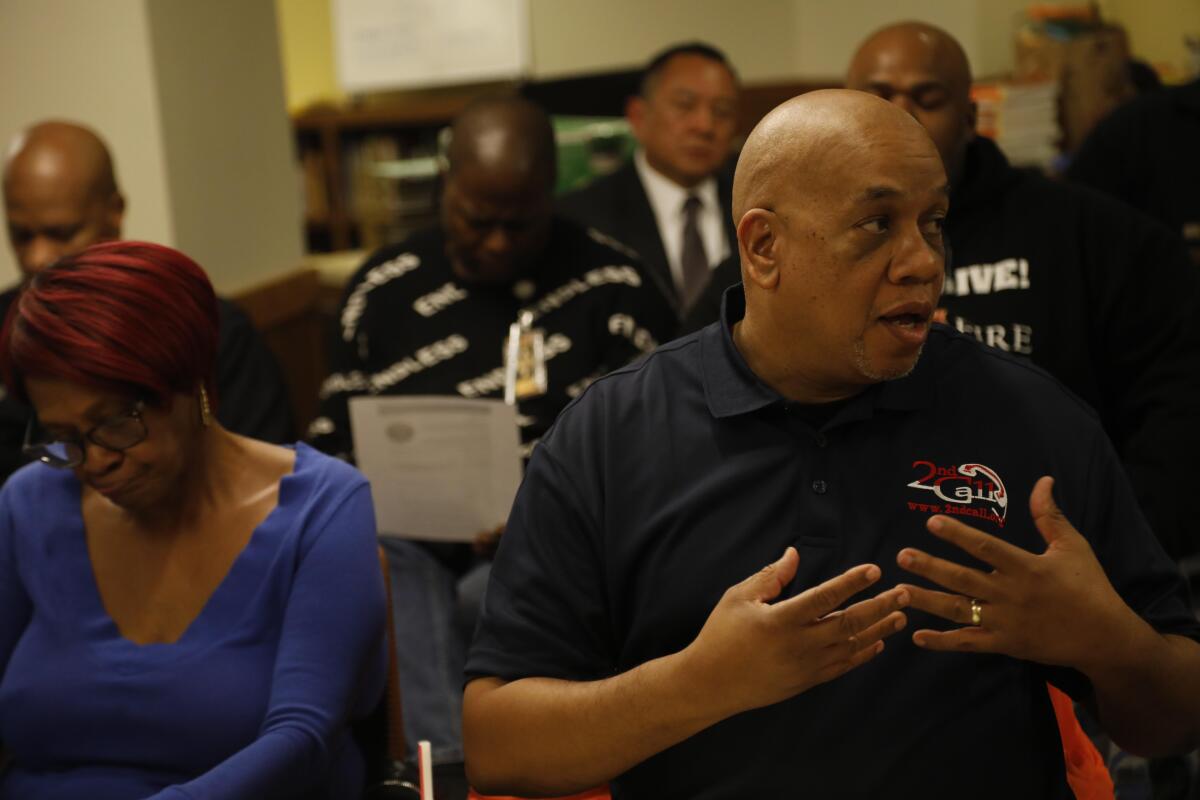

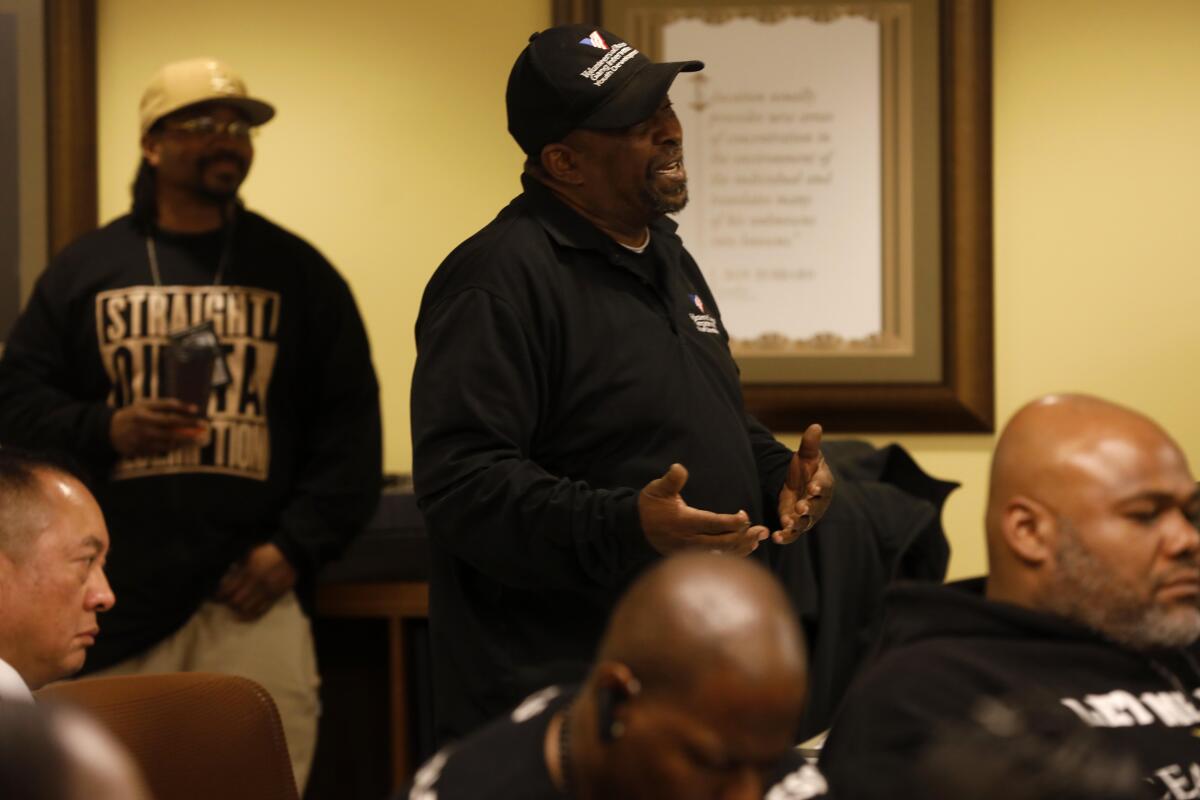

“We recognize the grief, the hole in the boat this circumstance has created. And we’re going to fix it,” Moore told a packed meeting of the CeaseFire antiviolence group in South L.A recently.

The chief’s visit was encouraging. “What I’ve heard from you in the last two weeks is something I’ve been waiting years to hear,” one man in the audience said, to nods and scattered applause from the crowd.

But decades of skepticism and resentment will be hard to dispel.

“I like that Chief Moore didn’t hide it. He didn’t put it under the rug,” said Skipp Townsend, a former gang member who now works as a gang interventionist to help resolve conflicts and head off violence.

“This is the exact same thing that was happening 20 years ago. It never went away,” Townsend told me. “It became normal to officers over the years. So at this point they’re comfortable with it. It may not be policy, but it’s their practice.”

He’s glad that the LAPD has acknowledged the wrong, is investigating itself and has promised to publicly release the findings.

“That’s a great way to change the relationship with the community, where people are saying: ‘We’ve been telling you this for years. No one paid attention.’”

I paid attention during those years. So did many criminal justice advocates, including the Superior Court judge who dismissed a case against a young man from Watts whose gang label didn’t stand up to scrutiny — and administered a tongue-lashing to the officers who’d targeted him for wearing baggy clothes and “loitering.”

Back then, gang injunctions were the LAPD’s primary weapon in the battle to rein in gang violence. Officers had wide latitude to add anyone they believed to be a gang member to an injunction list that would allow them to arrest the person just for being in the company of anyone else on that list.

The lists were overly broad, nearly impossible to get off of and a source of resentment and hostility in neighborhoods where, as civil rights activist Connie Rice put it then, officers “wouldn’t know a gang member from a Boy Scout…Anybody who’s ever said hello to anybody in a gang is [considered] ‘affiliated.’”

I remember law-abiding teens being stopped by police on their way home from football practice or while walking to the computer lab in their housing project to work on a school assignment. They were added to gang lists on the whims of officers, then targeted for arrests that cost them jobs, relationships and even college scholarships.

To the officers I talked with back then, they were collateral damage in a war that was saving lives by tamping down gang violence — a war that even the LAPD brass seemed to think justified whatever shortcuts officers took to keep gang members off the streets.

I see echoes of that era in this scandal today. It’s bigger than a handful of cops fudging the facts to keep their numbers up.

It spotlights flaws in the process of building intelligence on gang members that dates back to the 1980s, when Los Angeles was, like many cities, in the throes of a gang war fueled by drug dealing. Cracking down trumped down civil liberties. Hundreds, maybe thousands of people across California have unfairly been labeled gang members since.

Then, as now, to officially label someone a gang member, police officers need to satisfy two criteria from a list that includes attire, tattoos, location, arrest record, associates, self-admission and the word of a reliable source, which could be another officer.

“Self-admission” has always been a particularly convenient tool because, until the advent of body cameras, it’s been difficult for an alleged gang member to disprove. Its power is rooted in the officer’s credibility.

And it’s not only the LAPD that’s been capitalizing on that. A 2016 audit of CalGang, the state’s official repository of gang members’ names, found that more than 40 people listed in the database would have been less than 1 year old when they were added to the roll. And 28 of those babies were entered for “admitting to be gang members.”

To his credit, Chief Moore is bothered by that too. The gang database can only be a valuable tool, he said, if it reflects the integrity of police officers and earns the confidence of the community.

“It’s well intended, but not well executed in some parts of the city,” Moore admits. “At this point we have got to have a better way of understanding gangs and making the connections we need.”

Changes are underway on the state level, he said. And locally, the unfolding scandal in the LAPD is already leading to more accountability. Now body cam footage is being routinely reviewed and compared with officers’ reports of their field interviews before anyone is added to the gang database.

That’s a prudent and practical first step, given that an officer’s credibility is the single most important element in the gang member designation. But what still needs doing is a cultural fix that’s more challenging and absolutely essential.

This doesn’t seem to me to be shaping up as “a few bad apples” thing. We have to ask what it means when officers on one of the department’s most prestigious teams don’t even bother to align their accounts with what they know their body cameras are recording.

Moore is wrestling with that question too. And he’s unequivocally pledged to get to the bottom of this, root out offending officers and make changes to the system so it’s less likely to net innocent people.

“I want to determine quickly just how deep this goes,” he said. “Did they slant things because we’re measuring their work? That’s no excuse. These are police officers, they’re not seventh-graders.”

If officers believe they have to cheat or lie, either something is very wrong with the department, or they’re not fit to be police officers.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.