Amid coronavirus outbreak, healthcare workers take extra safety steps at work and home

- Share via

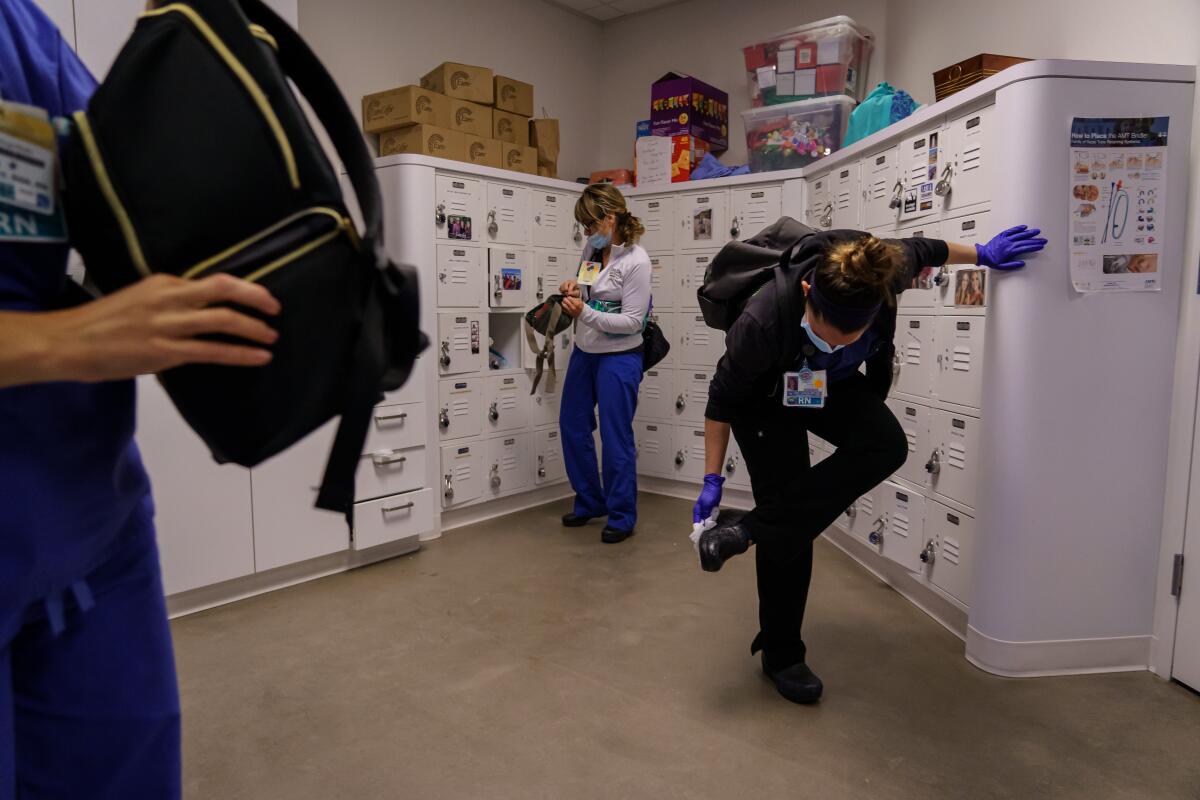

SAN DIEGO — Critical care nurse Erin Jenkins starts her COVID-19 catharsis in the locker room at UC San Diego Medical Center.

It is not enough to simply head home after 12-hour shifts working in the presence of the virus responsible for the global pandemic. Hard work is necessary to gain the kind of physical and emotional space needed for front-line workers to feel safe walking through their own front doors.

Changing into a fresh set of scrubs starts the ritual. Then it’s time for the scrub down. Everything — ID badge, shoes, smartphone screen — gets a swipe with an alcohol wipe as does every door handle on her path to the outside world.

Already sanitized, her work shoes nonetheless get special covers before they enter her vehicle, and they stay outside once Jenkins makes it home. Everything that was cleaned at the hospital gets cleaned again at the back door. Only then does it feel safe to move quickly through the house, touching nothing, and slip her clothes into the washing machine.

A shower marks the end of her personal process.

“I turn the water up until it’s really hot where it feels like it’s going to burn your skin off,” she said.

It’s a similar routine for Dr. Juan Tovar, an emergency medicine specialist and operations executive at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Chula Vista, which has seen a significant uptick in COVID-19 cases as the disease continues to put pressure on medical resources.

Down south, the going-home ritual is much the same, Tovar said, but includes a prayer huddle.

He has his own gray zone in his garage for wiping everything down one more time after initially cleaning everything at work. But lately he’s noticing that physical rituals and repetitive sanitation does not shed everything. “Once we really got into it, my dreams started changing,” he said. “Now, sometimes I’m seeing little COVID scenes in my sleep.”

While no cleansing routine can fully relieve the emotional weight of caring for very sick patients day in and day out, local hospitals do seem to be doing well at preventing the coronavirus from setting up shop in the medical centers that the entire community relies on to treat the sickest cases.

Public health officials say they have not yet detected a single outbreak — defined as three or more cases not connected by cohabitation — within the walls of a local hospital.

The vast majority of the 425 healthcare workers infected so far, said Dr. Eric McDonald, the county’s epidemiology director, have worked in skilled nursing facilities. Two healthcare workers have died so far, he added, but neither worked in a San Diego area hospital.

Working closest to the threat, staying safe is down to endless “donning and doffing” the extremely specific process of safely putting on and taking off layers of protective equipment without becoming contaminated. Hand washing is always the first step, followed by pulling on a protective gown, then an N95 respirator or powered positive-pressure hood and finally a face shield or goggles. Another round of hand washing comes next, followed by a pair of disposable gloves, pulled up to cover the cuffs of the gown.

After performing the necessary tasks, often beside teammates, it all comes carefully off, reversing the order — always, always, always folding items inward to avoid touching contaminated surfaces.

Colleagues watch each other religiously, making sure gowns are closed all the way in the back, there are no gaps at the wrists, and air hoses for hooded respirators are well connected to their filters.

It’s a tedious dance, performed so often it generates mounds of trash and makes every medical procedure take longer than it used to. Additional staffing is necessary just to keep everybody safe. But it’s also a luxury. Everyone has seen the news, how doctors in China and Italy and New York often end up going without everything they need to stay safe. Having patients arrive at a pace that’s slow enough that workers still have time to spot each other and follow safety protocols is a luxury in many places where the pandemic’s punch is landing hardest.

Jenkins takes a moment in between patients on a recent morning to make it clear that she and her fellow workers appreciate the assist from the community and its social-distancing efforts. Slowing down the pace of new patient arrivals is the bedrock that provides enough time to work safely.

“Those are the real heroes, the people who are staying at home, because they’re the ones who are saving thousands and thousands of lives,” Jenkins said. “If you need proof, look at what has happened in New York.”

So far, no one on the unit has gotten sick despite working daily with the sickest COVID-19 patients, including some whose lungs have become so damaged that their blood supply now must exit their bodies for oxygenation by a special ECMO machine.

Getting used to daily COVID-19 visits, and all that comes with them, is a gradual process, said Dr. Jess Mandel, director of pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine at UC San Diego Health.

“The first few times you go into the room of a patient with COVID, you’re very aware of putting everything on but, eventually, you know, it’s just what you do,” he said.

Adjustments have not just been about getting used to trusting that the personal protective equipment will work. The medicine is also different from the normal standards-driven routine that is the bread and butter of intensive care units the world over.

No one yet knows exactly how this virus is transmitted or what steps will work best to give patients suffocating due to viral inflammation in their lungs enough time for their immune systems to win the fight.

“Humility is a very important trait in a physician any time, and I think it has never been more important than when you’re dealing with a disease that’s 4 months old,” Mandel said.

Best practices, Tovar adds, are evolving daily. Mechanical ventilation, the process of using a special machine to help a patient breathe, has been a good example. A month ago, there was a feeling that ventilation after intubation, the process of inserting a breathing tube in a patient’s airway, should be undertaken relatively quickly after severe respiratory distress appeared.

“Now we’re finding, as we go along, that, with some of these patients, quickly intubating for the ventilator is not necessarily the best answer,” Tovar said. “We’re learning as we’re doing.”

Everyone is feeling in the dark for those subtle nuances of treatment that can make the difference between a patient going home or to a funeral home. Many are using modern social media networks to share tips and observations in real time, debating the pros and cons of different approaches in near real time.

Not having a clear set of guidelines has been one of the most unsettling parts of the COVID experience, Jenkins said.

“I’ve been a nurse for eight years now, and, for the most part, I feel like I’m generally in my groove; I know what to do,” Jenkins said. “But with COVID, it’s just too new, no one really knows for sure, and that’s a very scary component.”

Sometimes, it’s the sickest patients who are doing the teaching. Even the sickest among them can deliver positive surprises.

“In the beginning, I was like, that person’s definitely going to die,” Jenkins said. “Over the weeks, I see, oh, my gosh, this person turned a corner, and this person turned a corner, and this person turned a corner and oh, my God, that person’s talking now.

“They get sick really fast, but then, at some point, their immune system just seems to figure it out and they turn a corner and they’re OK.”

Families, though, are not sitting around waiting for that corner to be turned.

Many, Mandel said, spend their days furiously Googling for answers, coming forward by phone or video chat with demands for unproven drugs such as hydroxychloroquine or high-dose vitamins after reading one theory or another online. Despite the fact that he teaches medical students the latest in pulmonary care, Mandel has found himself defending the specific pressure settings used with a patient’s ventilator.

“I can’t ever remember a patient’s family talking to me about ventilator settings, but, in this case, they read something about pressure online,” Mandel said.

A big part of the adjustment has been regarding visitors, who have been banned from hospitals worldwide to reduce the risk of infection and also the use of personal-protective equipment.

This reality puts healthcare workers in the position of serving as conduits between patients and their families. Generally, Jenkins said, healthcare workers are happy to serve this function. But just how alone the visitor ban leaves her patients has been personal. It has forced her to imagine herself in the same situation.

“You’ll see someone who’s, like, your age, and you think, ‘Wow, my husband or my family can’t even be here with me if I do get sick?’ That’s horrifying,” she said.

The lack of access, Mandel added, demands a deeper commitment to communication from doctors. Family members often have so many questions that consultations can take much, much longer. It’s not, he said, just about conveying information on a person’s health condition.

“We’ve had to really make sure they know what’s going on to make sure they know that we are both competent and that we actually give a damn about their relatives,” Mandel said.

Sisson writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.