Thousands of cars protest in caravan through Oakland

- Share via

OAKLAND — Protesters in the Bay Area demanded justice for the killing of George Floyd for the third day on Sunday, when a caravan of thousands of vehicles drove through downtown Oakland for more than three hours.

The procession was organized by the Anti Police-Terror Project, a group co-founded by former Oakland mayoral candidate Cat Brooks, as a safe means to demonstrate against the deaths of Floyd and other victims of police brutality without violating social distancing guidelines.

“We’re in the middle of a pandemic that is inequitably and disproportionately impacting black and brown bodies, so it’s important for us to have different ways to protest,” Brooks said. “Not everybody wants to get out there and get tear-gassed or get out there and risk getting [COVID-19]. But that doesn’t mean that they’re not just as enraged as everybody else. They just need a way to protect themselves.”

To organize the thousands of vehicles driving slowly from the port through downtown Oakland and around Lake Merritt, the group broadcasted commentary and directions on its Facebook page and over the radio. People on bikes rode through the lines of vehicles and asked drivers to tune their radios to 88.1 FM.

Between songs by artists including Gary Clark Jr., Childish Gambino and A Tribe Called Quest, protest organizers delivered speeches, updated participants on the procession’s progress and told drivers where to turn because there were reports of people losing the caravan.

“We’ve got to fight back with love. We have to protect our own. We have to protect what’s right,” a speaker identified as Michael said during the radio broadcast.

“For those of you brothers and sisters that are not black, thank you,” Michael said. “Revolution requires everybody.”

More than 90 minutes after the protest began, many vehicles still hadn’t passed the point from which the first cars in the caravan had departed. KQED estimated that more than 5,000 vehicles were present.

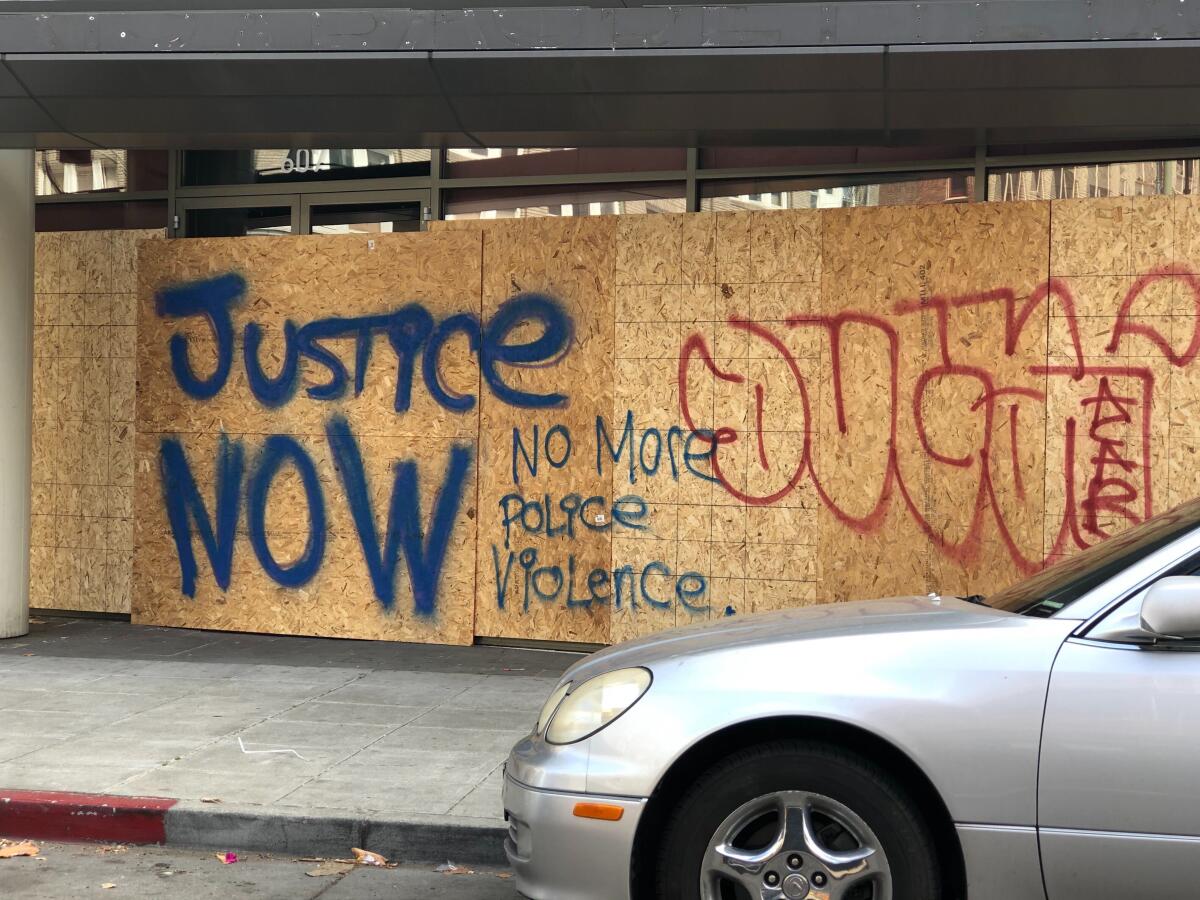

Remnants of Friday evening’s protests in Oakland — during which violence broke out as cops clashed with protesters, and some stores were damaged and looted — could be seen downtown during the caravan. Floyd’s name was spray-painted across many boarded-up businesses along with calls to “end police violence.” Graffiti on one side of the 12th Street BART station read simply: “Was it worth it?”

The signs on vehicles in Sunday’s procession invoked Floyd’s name, as well as those of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency room technician who was shot by police at least eight times in her Louisville, Ky., home on March 13, and Steven Taylor, a 33-year-old man who was shot by police in a San Leandro Walmart during what his attorney says was a health crisis in April.

Other signs covering the thousands of cars read “Black Lives Matter,” “Filipinos for Black power,” “A badge is not a license to kill” and “Justice now.”

Chants of “Black lives matter” filled the airwaves and the city as people blasted their radios from their cars and honked their horns along with the chants.

Several protesters said they saw this demonstration as the first opportunity to have their voice heard amid the pandemic.

Tracey Corder has lived in Oakland for six years and said that, although she has friends who participated in Friday’s protests, she is immunocompromised and felt more comfortable having her voice heard from a car. “People are making the best decision for themselves, but trying their best to stay safe and support each other,” she said.

Despite the risks of being exposed to the coronavirus and being arrested or targeted by police, she said it was important for her to show up in protest of the killing of Floyd and others, because “we can’t normalize it.”

“I’ve been to so many protests [over police brutality] in Oakland,” said Corder, who wore a shirt she got in 2014 that read “Don’t shoot.” “This is not the first. It continues to happen. And so anytime it happens, we have to show up, because this isn’t normal.”

Other protesters said this is one among many demonstrations on their calendars. Reyhaneh Rajabzadeh and Lincoln Daw, who drove together, attended Friday’s protests, and they plan to attend a march organized by Oakland Technical High School on Monday.

“I’m really hopeful that the privileged can ... keep the pressure on politicians and lead to substantive change so that police brutality against black people and other people of color stops,” said Daw, who moved to the Bay Area from Australia two years ago and works in tech.

As the procession made its way around Lake Merritt, a separate group of protesters began gathering in San Francisco. Thousands marched down Market Street in the afternoon and wrapped up around 6:30 p.m., before an 8 p.m. curfew that was set by Mayor London Breed in response to looting that took place after a peaceful march on Saturday. Like Friday’s protest in Oakland, it’s unclear who organized the San Francisco march.

Brooks said people had turned to her group for guidance on whether to attend Friday’s march. The Anti Police-Terror Project did not endorse the protest, but it didn’t discourage those who wanted to attend. Her group offered social distancing guidelines and organized a bail fund for those who might have needed it on Friday.

“It’s never our job to tell people what and what not to do,” she said. “But people do look to us to provide guidance and strategic thinking about how we hope people should engage.”

Brooks emphasized to the thousands of vehicles in the caravan broadcasting the program that tactics might vary, but it is important to take advantage of the movement that is happening across the country.

“How are we going to leverage all this attention and noise and rage and pain?” Brooks said over the sound of cars honking. “How are we going to leverage this and build something that actually moves the needle for change?”

“We can’t let this moment pass,” she said. “I love you, Oakland.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.