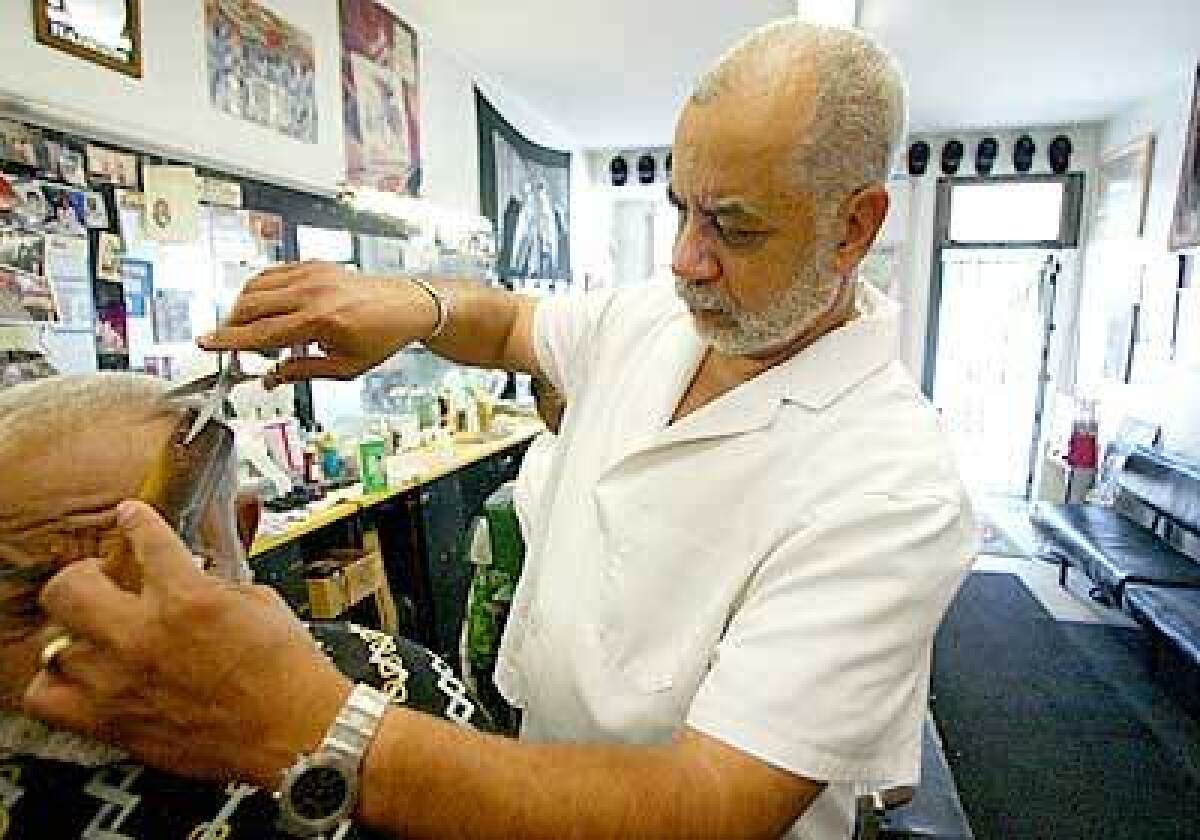

Tolliver’s barbershop in South Los Angeles is temporarily closed, but the conversation continues

- Share via

If these were ordinary times, I would have planted myself on a chair at Lawrence Tolliver’s barbershop in South Los Angeles, where everyone who walked in the door would have had something to say about the demonstrations in Los Angeles and across the nation.

But Tolliver was forced by the coronavirus to shutter his town hall clip shop, where his customers have been discussing every major event for decades, from the uprising following the Rodney King verdict of 1992 through to the lawless presidency of Donald Trump. I’ve never walked out of the shop without a deeper understanding and appreciation of Los Angeles.

I thought the next best thing next to being in the shop would be to talk to Tolliver and some of the regulars by phone, and my first call was to the man I’ve known for 20 years.

“I’m as conflicted as I could be, and I’m worried,” said Tolliver, 75.

He said he supports peaceful protest, but he decried the mayhem. He said he is exhausted by racism and police violence against people of color, but he loves and supports his son, a police officer.

“I never thought we’d have another riot here because the LAPD has made positive changes,” said Tolliver, who has photos of his favorite past LAPD chiefs on the walls of his shop, next to photos of President Barack Obama, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

Tolliver took a measure of hope in the fact that local demonstrations look like “a rainbow coalition of people,” but he thinks that in the last few years, the depths of racial division have been exposed and racial bigotry has been validated and exploited by President Trump.

“I just can’t relax, because I care so much,” said Tolliver. “I care about this nation and I care about this city.”

“To me,” said his wife, Bernadette, “the situation has gotten worse because of what’s projected out of Washington.” She said she’s deeply troubled by the looting, burning and vandalism in California and elsewhere, but she said wondered if vandals feel “emboldened and think they can get away with anything because with this president, look at his attitude” of self-interest and provocation.

“He’s confrontational with everybody,” Dr. Sandra Cox, a psychologist and longtime customer at the barber shop, which serves both men and women, said of the president.

As I spoke to Cox, Trump was in the Rose Garden, telling the world he supported nonviolent protests even as police in riot gear tear-gassed and herded peaceful protesters out of the way so Trump could hold up a Bible in front of a church and announce himself the president of law and order.

Cox recalls the uprising of 1965 in her neighborhood of South Los Angeles, where her family ran a business. And she recalls the echo, 27 years later, with the violence that followed the acquittal of officers who beat Rodney King to a pulp. In 1992, Cox wanted to do something to heal the city and comfort those who were traumatized but didn’t have easy access to professional care, so she started a mental health agency she runs to this day.

“The economic disparities and other issues are as bad now as they were then, if not worse,” said Cox.

Former state Sen. Rod Wright, another of Tolliver’s customers, says he’s seen forward movement followed by slippage again and again. After the Watts riots, he said, more people of color were elected and appointed to public office. Various community improvement programs were begun, too, and progress was made, said Wright.

“But [Ronald] Reagan came in and put the kibosh on a lot of that,” Wright said of the former California governor and president. And there was another factor that halted and even reversed progress, Wright said. The manufacturing and aerospace economy of Los Angeles collapsed.

“We actually had a decent job base. Firestone, GM, Goodyear, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin —– once they started hiring people, you saw home ownership like we’d never seen before and Los Angeles was one of the more affluent African American places in the world. But it all became unraveled.”

The reasons are many. But in the intervening years, Wright said, public policy and economic strategy fell under the control of Wall Street, and even Obama failed to loosen that grip on Washington.

One big difference with the current unrest, Wright said, is that the flash points of violence have moved north and to the west, all the way to Santa Monica. The majority of demonstrators may be protesting brutality and disparities in education, healthcare, criminal justice, jobs and pay, Wright said. But “a small group” of well-organized opportunists is out to wreak havoc.

“Racism is a disease and if you are not a person of color, you are not going to understand,” said Albert Gomez, a 26-year-old Tolliver’s regular who is half black and half Latino. “People need to continue to protest peacefully and speak their minds,” but violence “is only going to make things worse and it’s going to take longer for the economy to recover.”

That sentiment was shared by Rev. James K. McKnight, pastor of Tolliver’s church, the Congregational Church of Christian Fellowship.

“What does that look like after three months?” McKnight asked, adding that he understands the rage but remains a disciple of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s model of nonviolent protest.

“When businesses are torn up, what happens to the jobs and what happens when you have a police state? Do you think things are going to get better for poor folks? After the fires go out and the officers go to prison, where are we? Are we ever going to sit down at the table of responsible compromise and mutual respect, or are we always going to bring up our armament and hurt one another?”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

McKnight said he saw a speech by an Atlanta rapper Killer Mike, who gave him hope. The rapper invoked the long history of those who have fought for justice and implored Georgians to honor them by using their anger and energy not to burn, but to organize, mobilize, strategize and vote.

Carter Paysinger, who grew up in South Los Angeles and later served as principal of Beverly Hills High, said he watched televised news of demonstrations across the country with his 9-year-old son. They also saw a news story about the long history of police not being prosecuted for brutality.

“All these years later, I was having the same conversation with my son that my dad had with me after the Watts riots,” said Paysinger. “I told him about understanding that he could be in the right, but if he’s stopped by a police officer … you have to be absolutely respectful to the officer, keep your hands in view at all times and cooperate with whatever they’re saying. I told him the way you protest is to do it peacefully.”

And what did his son say?

“He said so if these cops killed those black people and didn’t have to go to jail, that’s not fair. We would have to go to jail if we killed somebody.”

Drew Palmer, an engineer who has worked as a youth mentor for 25 years, lost his composure as he talked about watching the video of the Minnesota cop who dug his knee into George Floyd for nearly nine minutes. The cop seemed nonchalant, Palmer said, noting that he had his hand in his pocket while Floyd was dying. It was as if that cop was sending a message to black America, Palmer said.

“I will keep kneeling on your neck and there’s not a damn thing you can do about it. The smugness, the smugness, the SMUGNESS of that officer. That imagery will be emblazoned in my mind until I die,” said Palmer.

I’ve known Lawrence Tolliver as a businessman, a community leader, a family man and a friend.

I watched him bury a son who died of cancer.

I walked with him to the polls the day he voted for Obama.

I watched him reel at the racially loaded language of division that carried Obama’s successor -- a president now trying to suppress turnout by attacking mail-in voting -- into the White House.

I have never seen him as distraught and discouraged as he is now.

“I’m an optimist,” Tolliver told me, as if trying to convince himself that he is.

As if trying once more to find his faith.

“I hope the good forces stand up and the people who want to do the right thing will make a difference, and we will survive.”

Steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.