Newsom should continue working with the Legislature on the housing crisis. Prop. 21 isn’t the answer

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Proposition 21 on the Nov. 3 ballot asks voters to decide how far government should interfere in the private marketplace to control residential rents.

It’s not about whether there should be government rent control in California. There is and has been for decades. It’s about how much — whether it should be substantially strengthened and extended to a lot more housing.

Proposition 21’s backers argue that much stronger control is needed to allow middle-income tenants to live within reasonable commute distance of their urban jobs — and to keep poor tenants under shelter and off the street.

“California used to be a very good place to live for people with only a little bit of money,” says the measure’s chief backer, Los Angeles activist Michael Weinstein, president of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

“Now we have the horror of 150,000-plus people living on the streets. And that’s the result of letting the marketplace run without control. Shelter is not a commodity, it’s a necessity.”

“Right now,” Weinstein told me Tuesday, “I’m looking down from my office window, and I see block-long cardboard boxes and tents. It’s an apocalypse.”

A new UC Berkeley poll shows 37% of voters support Proposition 21 to expand rent control in the state.

Weinstein’s office is at iconic Sunset and Vine in Hollywood.

Opponents of the citizens’ initiative counter that making the rental industry less profitable — in many cases leaving it a financial loser — would discourage construction of badly needed apartment complexes and ultimately drive rents even higher.

Gov. Gavin Newsom agrees with that argument. The Democrat announced his opposition to Proposition 21 in September, noting that he and the Legislature last year beefed up state rent control.

Newsom called the bill a “historic version of statewide rent control — the nation’s strongest rent caps and renter protections.”

“But Proposition 21, like Proposition 10 before it,” Newsom continued, “runs the all-too-real risk of discouraging availability of affordable housing in our state.”

Proposition 10 was the first attempt by Weinstein to pass statewide rent control. It was a more stringent measure than Proposition 21 and voters rejected it by a near-landslide in 2018.

Newsom wants to give the new law that he and the Legislature passed a good chance of working. It caps annual rent increases at 5% plus inflation for apartments older than 15 years.

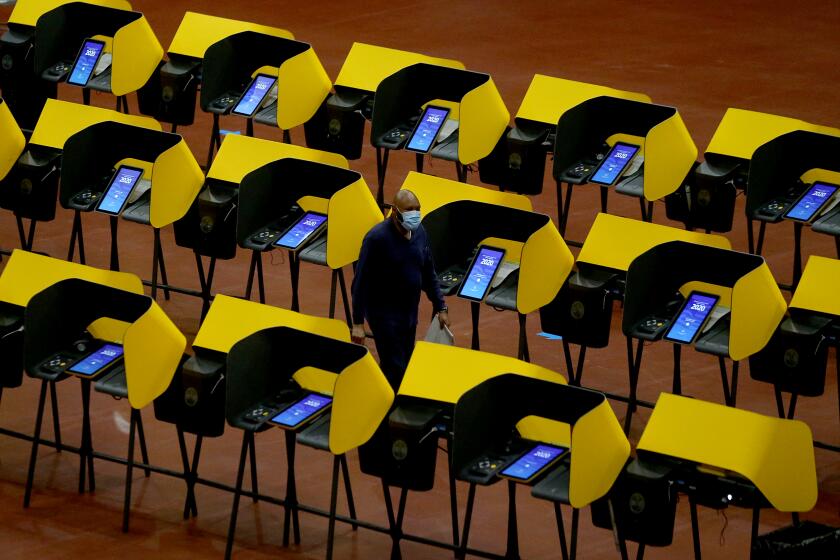

California’s November election will feature 12 statewide ballot measures.

The 15-year grace period is designed to give developers a chance to recoup a large part of their investment before rent controls take hold — and to offer an incentive to build.

The law also provides some tenant protections, requiring “just cause” for eviction after one year of occupancy.

Single-family homes and condos owned by individuals are exempt from rent control — but not those held by corporations and investors.

The new law took effect in January. But because of the pandemic-caused recession, it really hasn’t been tested. In many areas, the rental market has gone bust.

“We have huge vacancies in some places and lower rents,” says Debra Carlton, executive vice president of the California Apartment Assn.

“Tenants are dropping their keys at the front desk and leaving. If their jobs tell them they can work at home, they just leave the high-priced market and move further away to a lower rate. So, we’re seeing lower rents.”

Proposition 21 “will discourage housing construction at a time when we desperately need it,” Carlton says. “No builder is going to build in a city with the rent control this allows. They’ll just build next door. And tenants will have long drives.

“It’s going to make a bad situation worse.”

California’s rent control is already confusing, varying from place to place. Each city is allowed to adopt its own controls, within state restrictions.

Basically, there can’t be controls on housing built in 1995 or after. Nor can there be on other apartments constructed before 1995 if a city already had rent control then.

In Los Angeles, rent regulations can’t be imposed on any apartment built after 1978.

Landlords also can’t be told what they can charge new renters the first time.

Under Proposition 21, cities and counties could substantially expand their rent control to most housing more than 15 years old.

Rents for single-family homes would be controlled unless the owner had only two such dwellings — counting a personal residence. And even then, the home would need to be in a person’s name, not a trust or a partnership.

Landlords would be limited to how much they could raise the rent on new tenants — 15% all at once or over three years.

Opponents say this wouldn’t provide landlords enough rent to fix up a unit badly in need of repairs.

“I would no longer continue to invest in California,” says Al Wong of San Francisco, who owns several fourplexes and small apartment buildings. “I’d say, ‘Sorry. I can’t do this. This is not a business anymore. I’m going to go to Washington or Idaho or Nevada.’”

Rene Moya, the Proposition 21 campaign director, points out that 30% of California’s renters pay at least half of their earnings in rent — far too much to also afford utilities and food.

But voters apparently aren’t convinced. A recent poll by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found that likely voters are split — 37% yes, 37% no and 26% undecided.

I’m a no.

If California wants to control rents, government should build public housing.

Also, provide generous rent subsidies.

Newsom and the Legislature should compromise on a bill to impose new zoning requirements that allow for more multifamily housing. And streamline building regulations while reducing fees.

Don’t put all the burden on private enterprise.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.