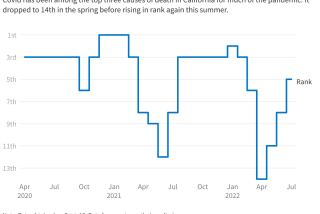

California’s COVID-19 death toll surpasses 60,000 even as conditions improve

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — The COVID-19 death toll in California has exceeded 60,000, an alarming statistic that comes even as conditions in the state continue to improve.

The state’s toll represents 10.7% of COVID-19 deaths nationwide. California is home to about 12% of Americans.

Although California’s death toll was lower per capita than in the other most populous states, COVID-19 has hit some communities particularly hard. The state’s lower-income Latino communities — home to many essential workers who often live in crowded housing — saw disproportionately high numbers of deaths while affluent areas saw lower numbers.

The milestone in fatalities, recorded this weekend, comes as California has achieved significant progress in slowing the spread of the coronavirus. Daily deaths and hospitalizations have plummeted, and the state has so far avoided the spring resurgence that has hit other parts of the country.

Beginning Thursday, all Californians age 16 and up will be eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine, bringing hope of further taming the coronavirus.

Some local governments and health systems have moved even faster to open vaccine appointments. City-run sites in Los Angeles this weekend began allowing anyone 16 and older to book vaccine appointments for openings as early as Tuesday.

Officials, however, warned that supplies of vaccine will still remain limited for at least the next two weeks and counseled patience as people seek to book an appointment.

Although California’s allocations of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are expected to remain relatively steady this week, the state — along with the rest of the nation — will see availability crater for the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Last week, 574,900 J&J doses were allocated to the Golden State. This week, that number will plummet to 67,600, an 88% drop, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

This nosedive for Johnson & Johnson will drive down the size of the state’s federal allocation from the 2.4 million doses received last week to 2 million this week and 1.9 million next week.

This would appear to fall far short of the rosier estimates shared more than two weeks ago, when the state announced plans to widely expand vaccine access — first to residents who are at least 50 years old, which happened April 1, and then to all California residents 16 and older starting Thursday.

Based on estimates at the time, officials said they expected California to be allocated about 2.5 million first and second doses per week in the first half of April, and more than 3 million doses in the second half of the month.

Officials believe the rise in vaccinations has played a role in turning the tide of the pandemic just months after the state experienced a devastating autumn-and-winter COVID-19 surge.

And while some experts have criticized California for acting too slowly to impose a stay-at-home order as the autumn-and-winter surge worsened, the business restrictions eventually imposed in much of the state in December and January have been credited with saving lives and protecting many California hospitals from tipping into the kind of catastrophe New York’s hospitals faced early in the pandemic.

California has the lowest cumulative COVID-19 per capita death rate of the eight most populous states in the nation, according to a Times analysis of Johns Hopkins University data. Besides California, the eight most populous states are Texas, Florida, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Georgia.

California has the 30th-worst COVID-19 death rate on a per capita basis among the 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

California’s cumulative COVID-19 death rate is 153 per 100,000 residents. New Jersey and New York have the nation’s highest cumulative death rates, with 280 and 260, respectively, per 100,000 residents. If California had the same death rate as New York, its cumulative COVID-19 toll would exceed 101,000.

The state has recently observed a dramatic slowing of the average number of deaths being reported daily. On recent days, California reported an average of 105 to 120 COVID-19 deaths — the fewest reported since the autumn-and-winter surge began. At its worst, in late January, California was recording as many as 562 deaths a day.

By the weekend, California was reporting an average of 110 deaths a day, a 14% decrease from the previous week.

The pandemic’s effect statewide has varied by region. Of California’s most populous regions, Los Angeles County has fared the worst. For every 100,000 residents, L.A. County has recorded 233 deaths. If L.A. County were a state, it would have the seventh-highest death rate.

The San Francisco Bay Area has fared far better; for every 100,000 residents, the Bay Area has recorded 79 deaths. If the nine-county Bay Area were a state, it would have the 45th-highest cumulative COVID-19 death rate among the 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Cumulatively, counties in Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley have reported the highest per capita death rates in the state. The 14 hardest-hit counties, in descending order, are Imperial, Los Angeles, Inyo, San Bernardino, Stanislaus, Riverside, San Joaquin, Tulare, Fresno, Merced, Kings, Orange, Madera and Kern.

A key contributing factor to the higher death rates in Southern California is the large proportion of residents who must work outside the home and live in crowded residences, which makes it easier for the coronavirus to spread once a member of a household becomes infected.

Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley generally have a higher social vulnerability than the Bay Area, meaning that factors such as poverty and crowded housing cause many of these communities to fare worse in a disaster like a pandemic.

Gov. Gavin Newsom faces a potential recall vote over his handling of the pandemic, with critics opposing restrictions he ordered that closed a number of businesses in order to slow the spread of disease.

Newsom has defended the measures as necessary to protect Californian lives and hospital operations and has projected optimism that the state’s economy will recover strongly. A UCLA Anderson economic forecast predicts that the state’s economy will recover faster than that of the U.S. as a whole; one factor is the number of California-based companies that produce technology to support how we work and socialize from home.

In general, of California’s regions, the Bay Area has been the most supportive of the state’s stay-at-home orders.

A Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll conducted in late January found that the Bay Area was most supportive of Newsom’s stay-at-home orders, with 57% expressing trust in state officials in setting rules to slow the coronavirus spread. L.A. County was split, with 48% expressing trust and 48% expressing mistrust. Majorities were distrustful of Newsom’s leadership in other regions of the state, including San Diego County, Orange County, the Inland Empire and the Central Valley.

A more recent poll, conducted in mid-March by the Public Policy Institute of California, found that just 40% of likely voters back a recall of Newsom, and 56% want to retain him as governor.

Support for removing Newsom was lowest in the Bay Area, with 27% backing the idea. In L.A. County, 40% backed a recall; 41% did so in San Diego and Orange counties. There was more support for a recall in the Inland Empire, where 47% backed the idea, and the Central Valley, where 49% say Newsom should be replaced.

Lin reported from San Francisco and Money from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.