My encounter with a football miracle: In search of the stories behind ‘The Play’

- Share via

I looked up into the Big Man’s eyes and screamed and screamed. I screamed at close to the top of my lungs. Then I shouted some more.

I wanted to make sure the stranger heard me. So I hammered downward with both hands on the Big Man’s shoulders. They loomed like twin mountains, strapped into a set of massive shoulder pads, wrapped in a uniform of deep blue.

So I pounded and bellowed. Pounded and bellowed. And the Big Man seemed to get it. Thank goodness, he seemed to get it. Because, at 6 feet 3 and 290 pounds, it was important that he understood that — although I appeared frantic — I came in peace.

I have cherished that moment for the intervening four decades. I love to tell the story of how I committed verbal assault (and near-battery) on George Niualiku, an offensive guard on the University of California football team. And I lived to tell about it.

My small flight of insanity was not unique that late fall afternoon in Berkeley. All around us on the field at California Memorial Stadium, others came unhinged. They howled like toddlers, “Wooooo-hooooooooooooo!” They Bear-hugged strangers. They raised their arms aloft as if they had won the heavyweight championship.

That’s the way it goes when you have witnessed what Cal radio play-by-play announcer Joe Starkey called “the most amazing, sensational, dramatic, heart-rending, exciting, thrilling finish in the history of college football.” The details would slowly come into focus over many years, as the escapade dubbed “The Play” grew into both a sports phenomenon and my personal obsession.

Working on a book about the inexplicable ending of that showdown game between Cal and Stanford, I interviewed coaches and players, fans, journalists and officials. I learned a lot about football, but more about brotherhood, regret and hope.

Yet, until this fall, I had never met Niualiku, the individual who literally loomed largest in my memory of Nov. 20, 1982. I wanted to know what he remembered of our encounter, so many seasons ago, and what The Play meant to him.

::

The 124th annual gridiron showdown between UC Berkeley and Stanford — known to Bay Area true believers as the “Big Game” — is scheduled for this Saturday. A year shy of its 40th anniversary, the legend of The Play lives on. An ESPN feature, hosted by retired NFL star Eli Manning, again hailed it last month as the “most fantastic moment” in 152 years of college football.

The Play remains unparalleled because UC Berkeley had all but certainly lost — seemingly defeated by a stunning John Elway-engineered scoring drive and a Stanford field goal that left just 0:04 on the clock — before Cal’s kickoff return team went brilliantly schoolyard, in a moment that remains video clickbait to this day.

The method of the Golden Bears’ deliverance defied logic and all precedent: four players knitting together five laterals and a cartoonish scamper that carried them through, over and around not only 11 Stanford football players but 144 members of the Leland Stanford Jr. University Marching Band.

The football rivalry between the two great universities is one of the oldest west of the Mississippi, with multiple games decided by last-minute heroics and others producing unthinkable upsets.

In 1982, Elway quarterbacked the kind of late-game drive that would become his signature in a Hall of Fame NFL career. His marquee moment came with less than a minute left, when he dodged a fearsome charge by the Cal defensive line and threw a 28-yard laser on fourth down and long. Four plays later, a 35-yard field goal seemed to ensure a 20-19 win for Stanford.

But Elway and the Cardinal had called time out too early. Even as Stanford players mobbed the field, claiming victory, four seconds remained — an eternity for architects of the unthinkable.

In the chaos and dismay that followed on the Berkeley sideline, some Cal players talked to coaches about downing the kick, leaving time for one last Hail Mary pass by quarterback Gale Gilbert. No one told that to the Cal kick return team.

In the end-of-game confusion, Cal mustered only 10 of the standard 11 players for the Stanford kickoff. Luckily for the Bears, two of them were Kevin Moen and Richard Rodgers, lethal hitters on defense and, importantly, former option quarterbacks in their high school days. They knew how to handle the ball.

“Oh my God. The most amazing, sensational, dramatic, heart-rending, exciting finish in the history of college football.”

— Joe Starkey, Cal radio play-by-play announcer

Over the din of the Stanford band’s victory song, “All Right Now,” Rodgers didn’t wait for a command from coaches. He called most of his teammates into a huddle, shouting that they had to get rid of the ball if they fell into trouble. “Don’t fall with the ball,” fierce No. 5 declared. While thousands of Bears fans (this one included) hung their heads in defeat, a tiny seed of hope had been planted among the Berkeley 10.

Moen fielded the bounding squib kick from Stanford, six yards behind midfield. He stutter-stepped to his right and then back to his left. With red-and-white defenders bearing down, Moen threw overhand to Rodgers. Trapped along the sideline, he shoveled the ball back to Dwight Garner, a freshman running back. Garner shimmied and cut back, but five Stanford tacklers swarmed over him.

Fans from Palo Alto will forever insist that Garner’s shin and knee had hit the ground and that The Play should have been declared dead right there. Fortunately, the officials had a more laissez-faire (or obstructed?) view. They neither blew their whistles nor threw any penalty flags against the Bears. With white jerseys pinning his arms, Garner heard Rodgers calling to him. He barely managed to push the ball free.

The Bears’ field marshal grabbed it, wheeling to his right, finding a bit of open turf and striding into Stanford territory. With more white shirts again closing in, Rodgers lateraled for the second time, flicking the ball back to Mariet Ford, No. 1, a fleet wide receiver who already had one touchdown — a stunning layout catch in the second quarter.

Stanford band members, assembled just beyond the north end zone, already had exploded onto the field after Garner went down. (“We thought WE were the show,” one band member told me.) As Ford sped forward, a sea of red-coated musicians cavorted and pranced across the south end of the field, foraying past the 20-yard line. Ford ran past the interlopers and flung himself at the last serious obstacle: three Stanford players.

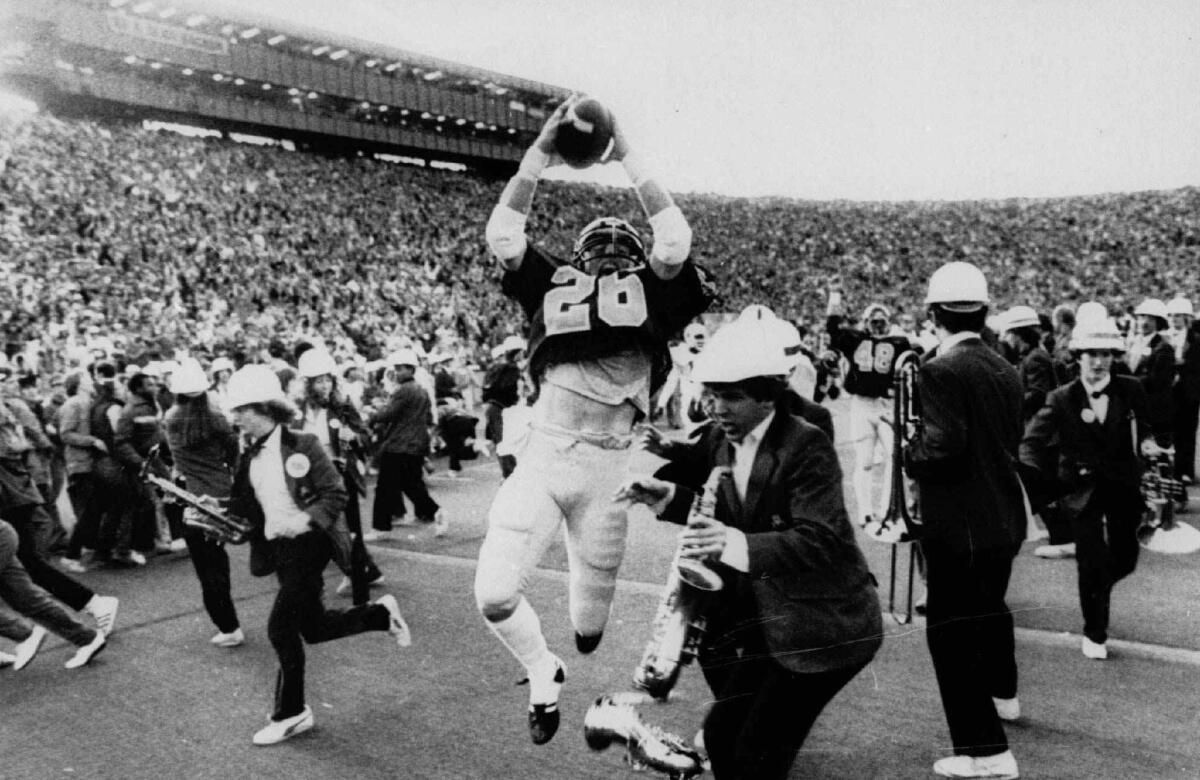

Ford’s leap took out the Cardinals, just as he heaved the ball over his right shoulder. No. 1 would say in the postgame locker room that he sensed Moen running somewhere behind him. The strapping safety, the first man who had touched the ball, would also be the last. He caught Ford’s desperation heave and rumbled the final 25 yards, past saxophonists, clarinet players and one last, befuddled Stanford linebacker.

Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite would write a year later of Moen’s “determined, full flight” and the rhapsodic band members darting to safety.

“Like a Red Sea,” Fimrite wrote, “they parted for the miracle worker.”

With a final, exultant leap, the 6-foot-1, 200-pound Moen brought the ball down on the head of trombone player Gary Tyrrell, who stood in at 5 feet 6 and 148 pounds. Tyrrell went down, while Moen romped through the end zone and into history.

Tyrrell, now a retired Silicon Valley financial executive, and Moen, who sells real estate on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, have been linked in Big Game lore ever since. Now as warm as brothers, they appear together on TV and radio on each of the The Play’s major anniversaries.

::

In the hours, days and decades that followed, The Play would be immortalized on T-shirts, re-created with animated Lego figurines and become the subject of a winning 2016 documentary. At 2018’s Big Game, fans received a Moen bobblehead, which quickly became an EBay favorite.

As thoughts turn to what promises to be a gaudy 40th anniversary celebration next year in Berkeley, it remains hard to top the breathless, inimitable words of Starkey in that moment. The veteran radio man had sounded near his wit’s end as The Play unfolded. Once referee Charles Moffett threw his arms in the air (confirming the touchdown after less than a minute’s deliberation with five other officials), Starkey erupted.

“And the Bears ... the Bears have won ... the Bears have won!”

The Play returns by accident for most football fans, often popping up on highlight shows. I have gone looking for it for years, seeking any opportunity to wallow in the joy and mystery of that moment. As a journalist, I have a calling card to contact characters, major and minor.

I had been sports editor of the student paper, the Daily Californian, so I already had a full-immersion course in Cal football. Two of my college roommates worked in the Cal athletic department. We routinely were among the first in the stadium for home games, sometimes forced to displace (even more) callow frat guys who thought they could cordon off 40 prime seats for their “bros.”

We came from a generation of young men who felt shy revealing our real hopes and dreams. So we bonded in a culturally acceptable way, the connection forged in frequent misery, as the Golden Bears persistently devised diabolical new ways to disappoint. Our commitment to Cal football felt deep, tribal. On the night before the 1978 Big Game in Berkeley, eight of us broke into Memorial Stadium. We slept on the field. (Apparently unaware of our sacrifice, our lads lost, 30-10.)

Unlike many of the landmark events I would go on to cover — shootings, riots, wildfires, presidential elections and a war — the 1982 Big Game came with a happy ending. By the early 2000s, I wrote how The Play symbolized possibility and enduring hope.

Even 20 years later, remarkable ending to Cal-Stanford game revives vivid memories

Setting out to recapture The Play, I naturally discovered many competing narratives: Stanford coach Paul Wiggin struggled to recover from the loss. Cal coach Joe Kapp celebrated and stewed, figuring he never got enough credit for the win. Members of Stanford’s unruly “scatter” band still relished those halcyon days, when they felt like young rock stars. There was the tragic aftermath of Ford, seemingly a model citizen, who would be convicted of killing his family and sentenced to 45 years to life in prison.

And, happily, I would find Niualiku.

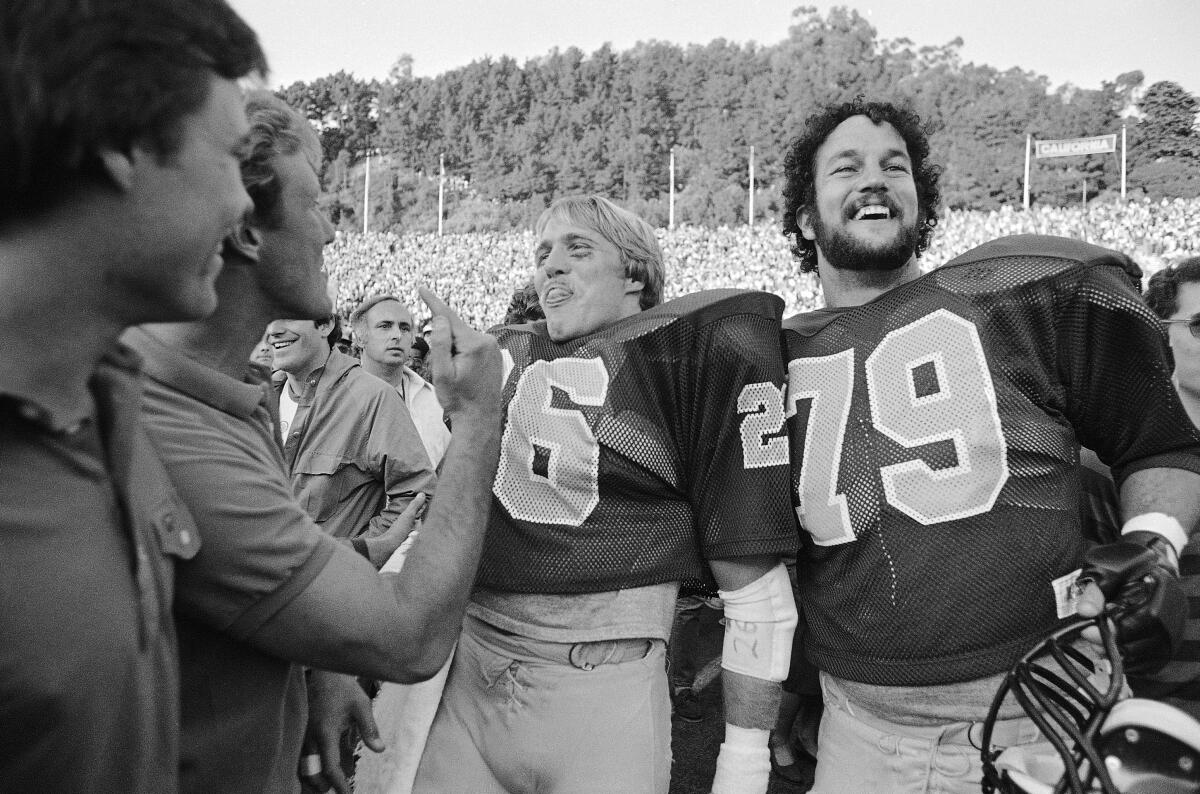

Over the years, my recollection of accosting this titan on the postgame battlefield blotted out many others. He was one of the first players I encountered. And I felt an added joy celebrating the moment with an interior lineman, the men too seldom unrecognized for their sacrifice. Niualiku’s stature only grew as teammates described his immense strength, his durability (sitting out only a handful of plays the entire season) and his smarts.

Teammate Fred Williams, a defensive back, rhapsodized about his buddy. And I learned that Williams was another Bear with a reputation for getting the job done, as well as being a student of politics and history and one of the most perceptive on a team of thoughtful men.

“Fred has no frills. He doesn’t talk s—,” Niualiku said. “He does the job,” the Big Man said, enhancing the praise by putting it in the present tense.

To me, Williams and Niualiku epitomized something I loved about The Play. It had been performed by a bunch of journeymen. Several of the principals had short or glancing careers in pro football, but none became stars. The two long-ago sidekicks — one the son of Black dairy farmers in the Central Valley, the other of Tongan immigrants who ended up in South San Francisco — represented the ensemble power of that Cal team.

Born in the South Pacific, Niualiku came to America in elementary school, with parents searching for opportunity. He earned a political science degree from “Bezerkeley ... a place with all different kinds of people. It didn’t matter. When I arrived, it felt like, ‘Wow, I am home.’ ” He made a career as an operations supervisor for a beer distributor. Williams is a real estate mortgage consultant.

I requested an audience on a recent Sunday morning with the two old teammates, now both 60. They stay in touch, if less frequently than in years past.

A couple of days later, we greeted one another like old friends at a coffee house across from campus. We quickly whipped through quips about our old-man injuries, marveled at how we had all found spouses much savvier than ourselves.

When I naively asked how amped and, perhaps, mouthy the team must have been, walking out of the tunnel into a stadium filled with 75,662 back on that November day in 1982, the pair gently demurred.

“I was thinking about my assignments,” Niualiku said.

“I didn’t have time for trash talking,” Williams said. “It’s like ‘Let’s just line up and do it.’ ”

Niualiku and I soon realized that we had shared a certain lack of faith 39 years ago. After Stanford’s field goal, I slouched back onto the hard metal bench in the Berkeley student section, high above the 50-yard line. It took a buddy’s reminder that four seconds remained to rouse me, skeptically, to my feet.

By the time Moen grabbed Mark Harmon’s fateful kick, Niualiku already had walked all the way back to the exit tunnel at the stadium’s north end. Alone. “I guess you could say I was a sore loser,” he chuckled.

He was about to climb the stairs to the locker room when he heard the boom of the cannon that punctuates every Berkeley score. “I am thinking, ‘Oh my God, there is something very wrong — or very right — here,’ ” Niualiku said. “By the time I got back to the field there were already mobs of people. Everywhere.”

I had to know: Did Niualiku recall a particularly frenetic fan, pummeling him and shrieking?

“I didn’t know who it was, of course. But I do remember somebody pounding on me pretty good,” the Big Man said. “And it was OK. It was a happy thing. A happy, happy thing.”

That was good enough for me.

In the intervening years, much has been said about who deserves credit for the miracle finish.

I have visited with Coach Kapp, the former NFL star whom Sports Illustrated once dubbed pro football’s “toughest Chicano.”

Players said he promoted a never-say-never ethic on arriving that year in Berkeley, his alma mater. He had also fortuitously instituted a routine during practices: Players would run the field while tossing a football, rugby style, while others tried to stop them. Everyone acknowledged that the “grabazz” drill looked a lot like the anarchy unleashed on Stanford on that Nov. 20.

The Play’s four famous lateral-makers fulfilled the roles they had grown into through their college careers. Moen, a stolid senior, fielded the ball and eventually scored “because he was always that dependable guy, in the right place at the right time,” Williams said. Ford executed the spectacular no-look lateral because he was a “diva,” known for making plays with panache, Williams said. And Rodgers, whom teammates called “The Rock,” orchestrated the whole endeavor, with two laterals and his insistence that his teammates not give up.

“He had been a leader all year. The ringleader,” Niualiku said. “When he said something, it commanded respect. No one deserves more credit than The Rock.”

Lost by commentators and impossible for outsiders to assess was something else, said Williams: The teammates’ deep commitment to one another. Niualku nodded in agreement. Bonding deeply with teammates mattered. “It’s the hunt,” he said, “not the kill.”

“George and Richard and Kevin are more important to me than The Play. But The Play is a direct result of that brotherhood,” said Williams. “Along with commitment, effort, hard work, athleticism. They kind of become one and the same, right?”

People don’t like to talk about it in a macho game, Williams concluded. “But the vibe matters. And it was love. That love part? I think it made all the difference.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.