A wealth of cash in L.A. Unified but for how long?

- Share via

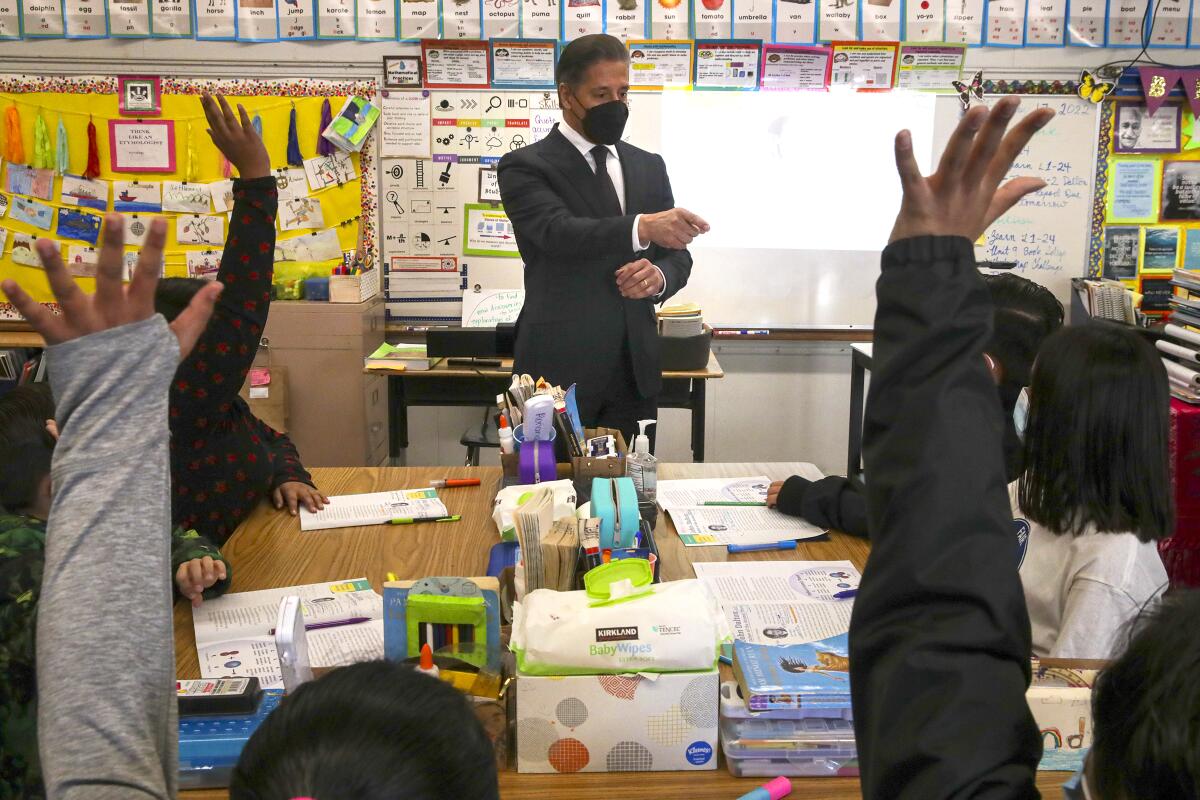

The financial forecast for Los Angeles schools calls for relatively blue skies for three years — including $3 billion left over at the end of the current school year — but warns that there could be serious shortfalls later, offering both opportunity and risk for the ambitious agenda of new Supt. Alberto Carvalho.

The funding picture, presented at Tuesday’s school board meeting, represents an improvement from the previous update in December. That earlier forecast had predicted that the 2023-24 school year could be financially shaky. That’s not the case any longer.

The district’s general-fund revenue for the current year is more than $10 billion, while spending is about $9.43 billion. That surplus will enlarge an already healthy reserve.

There is so much available funding that state rules require the district to quickly commit to spending an additional $1.7 billion or receive a waiver allowing the district not to comply with regulations.

“The amount of money that is coming into K-12 has heretofore been not witnessed,” district Chief Financial Officer David Hart told the school board.

The short- to mid-term positive outlooks bode well for Carvalho, who started his tenure in L.A. in February and whose agenda includes creating new programs, expanding existing, successful ones and reducing class sizes where it could have the most benefit.

But there’s an accompanying dark cloud. From July forward, the district is projected to spend about $1 billion more than it will take in over a two-year period. The district also must wrestle with underfunded retiree health benefits.

“It’s not just about budgeting for this year,” Carvalho said. “It’s also the long-term game.”

Altogether, the district must manage a unique moment of feast and potential famine, said school board President Kelly Gonez.

State and federal support “has enabled us to be in a strong financial position and to have the resources needed to address the deep impacts of the pandemic,” Gonez said. “However, our three-year outlook highlights that we must swiftly address the systemic issues which imperil our future financial position.”

There’s another element in play as well. The contract with the teachers union expires at the end of June. Union leaders are calling for pay increases, better working conditions and support services, and class-size reductions across all grades and school types — which would be more expensive than Carvalho’s proposed targeted approach.

“LAUSD’s historically high reserves, well over $2.5 billion by the end of this current school year, paves the way for a new path — a path for investment in Los Angeles public education and our communities,” Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, said in a statement to The Times.

Other unions will expect their members to receive whatever pay raise that teachers get.

Tuesday’s financial report stated the situation in sober bureaucratic language: “The district continues to be challenged with a structural deficit wherein current year ongoing expenditures are greater than projected ongoing revenues.”

Ending that deficit spending — whenever that happens — could mean sweeping program reductions and layoffs. And that’s not factoring in the possibility of an economic recession, which could reduce revenues from taxes.

The long-term budget reality is likely to include closing some schools, consolidating others and subsequently handing over all or portions of campuses to privately managed public charter schools, which, under state law, have a right to classroom space. To district planners, consolidating schools appears almost inevitable — because an under-enrolled school brings in less state funding than is required to operate the campus.

State and federal funding is fundamentally based on enrollment, which is falling rapidly, apparently accelerated by the pandemic. Enrollment peaked at 747,000 students in 2003. It now stands at 430,142 and is expected to fall below 400,000 in two years. A similar trend is happening statewide, although few places have dropped as steeply as L.A. Unified.

The domino effect of shrinking enrollment already has been playing out. Crenshaw High — once with more than 3,000 students — is down to about 500, and its legendary football program has trouble fielding a squad.

Selma Avenue Elementary in Hollywood has closed — its premises are being used by a charter school.

Three school communities — those of Trinity Avenue Elementary and Pio Pico and Wright middle schools — are embroiled in clashes over planned or possible closures, leaving longtime residents outraged at the potential loss of local institutions and neighborhood anchors.

“L.A. Unified continues to see declines in enrollment as demographics change and lack of affordable housing pushes families out of Los Angeles,” Gonez said. “We must take steps to ensure our families can continue to afford to live in L.A., parents continue to choose our schools and to address the budgetary challenges that confront us.”

The pending closures and currently understaffed campuses — due to unfilled vacancies — make the current wealth already seem illusory, as principals and teachers struggle to get students caught up to their pre-pandemic academic pace and deal with their social and emotional issues.

Parent leader Christie Pesicka, who spoke at the meeting during the public comment portion, said many parents have concluded that “the money isn’t making it to the school. What happened to our record funding?”

“My principal is begging parents for donations to fund [teachers aides], sanitation staff and basic enrichment,” said Pesicka, who is part of parent groups that are critical of the school district and teachers union. “We are in an educational epidemic that demands urgency.”

So how does a district that spends more than it receives end up with so much extra cash?

The budget is flush because of COVID relief aid, a one-time boost; record state tax revenues, which fluctuate with the economy; and previous, unspent relief funds. After initial fears of a COVID-related financial disaster, the nation’s second-largest school system has had, for more than a year, more money on hand than it could spend — a historical anomaly.

That money has paid for major technology purchases and upgrades, food distribution to families, raises for employees and the nation’s largest K-12 school district-based COVID-testing program. The weekly testing of all students and staff comes at a projected cost of about $600 million for the current school year.

Hundreds of unfilled teaching and counseling positions have contributed to the surplus but left students short on services that had been seen as necessary to help them.

Former school board member David Tokofsky, who works as a consultant to the administrators union, said the pending financial reckoning is not as stark as it appears because projections don’t take into account that state funding typically increases every year.

“The district is in a good place for five years — if they don’t rush and spend all the money in two years,” said Tokofsky, adding that slower spending could require some changes to state and federal regulations. “It will be a rare opportunity to truly have a strategic plan that moves to improve learning.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.