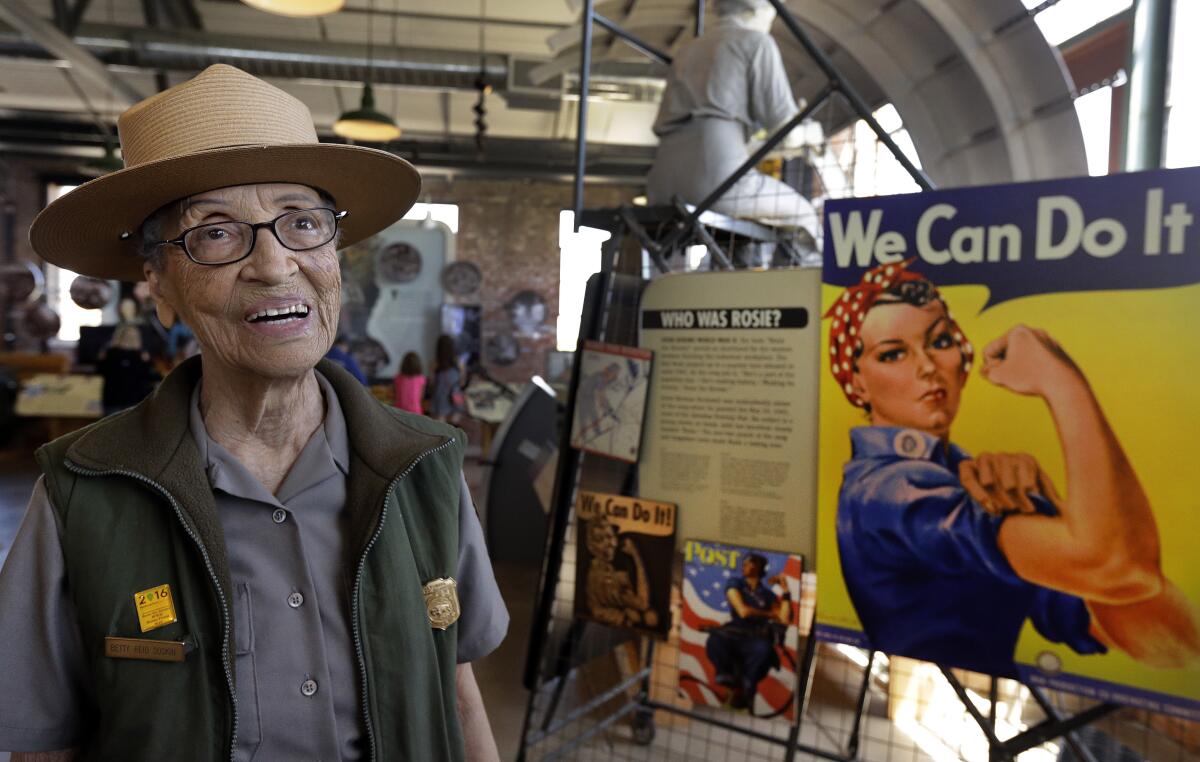

Ranger Betty Soskin, who shared untold stories of WWII civilian life, retires at 100

- Share via

Betty Reid Soskin, the country’s oldest active National Park Service ranger, retired Thursday at the age of 100.

As a ranger, Soskin shared her personal experiences with the public as an African American woman working on the World War II home front in Richmond, Calif., illuminating the stories of women from diverse backgrounds who joined the civilian war effort.

Soskin, who celebrated her birthday in September, spent her last day on the job heading up an interpretive program for the public and visiting co-workers at Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, according to the park service.

“Being a primary source in the sharing of that history — my history — and giving shape to a new national park has been exciting and fulfilling,” Soskin said in a statement. “It has proven to bring meaning to my final years.”

Soskin became a permanent NPS employee in 2011 and has since led public programs sharing her memories and observations at the park’s visitor center.

Before taking on the role, Soskin participated in meetings with the city of Richmond and the NPS to develop the general management plan for the new park, which was established in October 2000. She also worked with the park service on a project to uncover untold stories of African Americans who worked on the war home front, which led to a temporary position with the NPS when she was 84.

“Betty has made a profound impact on the National Park Service and the way we carry out our mission,” NPS Director Chuck Sams said in a statement. “Her efforts remind us that we must seek out and give space for all perspectives so that we can tell a more full and inclusive history of our nation.”

Soskin grew up in a Cajun-Creole African American family that settled in Oakland after a historic flood devastated their home in New Orleans in 1927, according to her NPS biography. She was 6 when she arrived in East Oakland, she said during an educational talk titled “Of Lost Conversations.”

Her parents joined her maternal grandfather, who had resettled in the Bay Area city at the end of World War I.

Her grandfather’s family “followed the pattern set by the black railroad workers who discovered the West Coast while serving as sleeping car porters, waiters and chefs for the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railroads: They settled at the western end of their run where life might be less impacted by Southern hostility,” the biography reads.

During World War II, Soskin worked in a segregated union hall as a file clerk, where she said Jim Crow was ever present.

In “Of Lost Conversations,” she reflects on her disappointment with an NPS film made about the World War II home-front effort in Richmond.

The filmmakers, she said, went with “the Hollywood ending,” in which, “[w]e all got together for the sake of democracy and we set our differences aside.”

The reality was harsher. It was about a decade before the labor movement would be racially integrated, and the unions created what were known as auxiliaries, workplaces where Soskin said black workers were “dumped.”

“Jim Crow was really the other name for auxiliary,” Soskin said.

She added, “Even then” — in 1942 — “that was a step up.”

“It would have been the equivalent of today’s young woman of color being the first in her family to enter college,” she said.

Three years later, in 1945, Soskin and her husband, Mel Reid, opened a music store. Reid Records shuttered less than three years ago.

Soskin also worked as a staffer for a Berkeley City Council member and field representative for two members of the state Assembly representing Contra Costa County.

According to her biography, Soskin gained national prominence when she was tapped in 2013 — as the oldest ranger — to speak about the government shutdown.

Two years later, the park service selected Soskin to participate in a Christmas tree-lighting ceremony at the White House, where she introduced President Obama for a PBS special.

In 2019, Soskin suffered a stroke, but she returned to work in early 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. She said she is immensely grateful for the opportunity to share her life experiences as part of her job with the park service.

“To be a part of helping to mark the place where that dramatic trajectory of my own life, combined with others of my generation, will influence the future by the footprints we’ve left behind has been incredible,” Soskin said.

Naomi Torres, acting superintendent of Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park, said the park service is grateful to Soskin “for sharing her thoughts and first-person accounts in ways that span across generations.”

“She has used stories of her life on the home front, drawing meaning from those experiences in ways that make that history truly impactful for those of us living today,” Torres added.

The Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park will celebrate Soskin’s retirement on April 16 in Richmond. Details can be found on the park’s website.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)