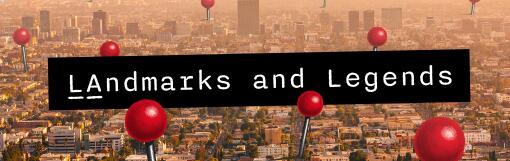

Martyr, crackpot, tree-hugger and more — the people behind SoCal’s mountain peaks

- Share via

It’s up there on the facade of the Jesse Unruh state office building right off the Capitol mall in Sacramento: “Bring me men to match my mountains.”

It’s the most remembered line that ever flowed from the pen of a 19th century New Hampshire poet, Sam Walter Foss, of the thumpety-thump school of verse, a man who knew only the New England ranges that stood puny by comparison to the Western summits he never saw.

As for the match between some of Southern California’s men and mountains, we’ll be the judges of that.

Let’s begin with the saints. Because, well — why take chances?

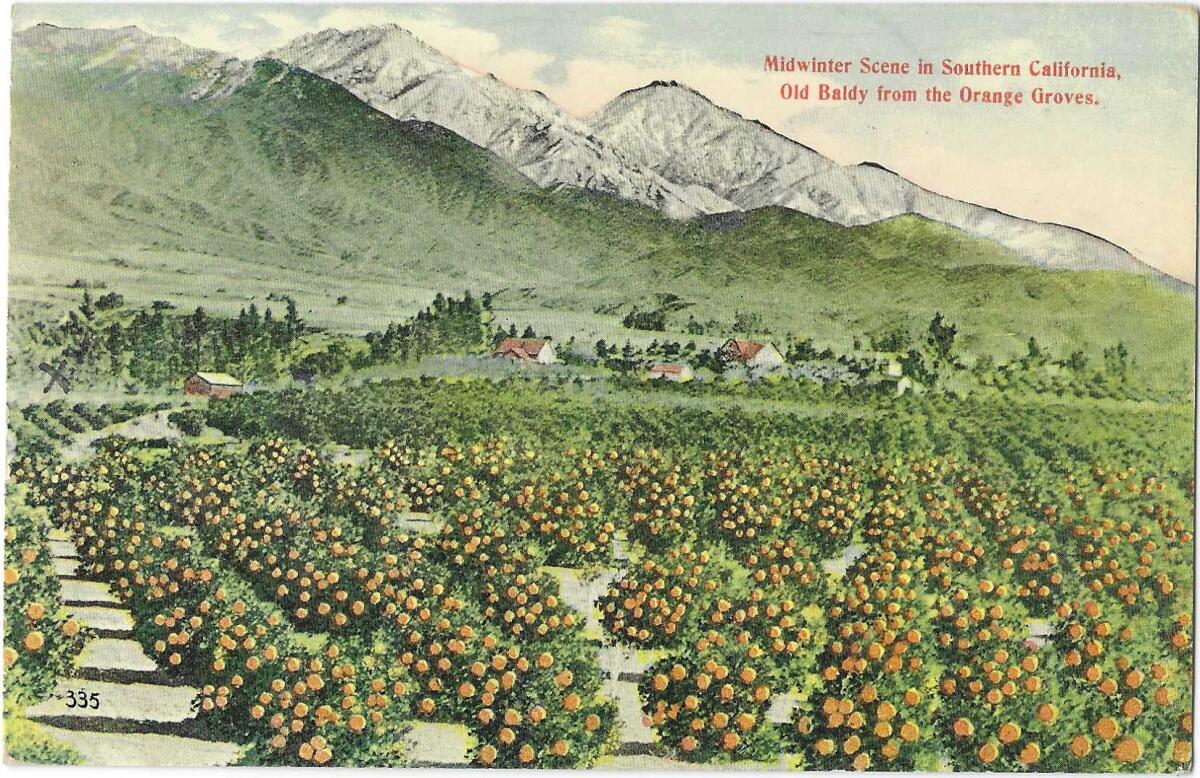

Mt. Baldy

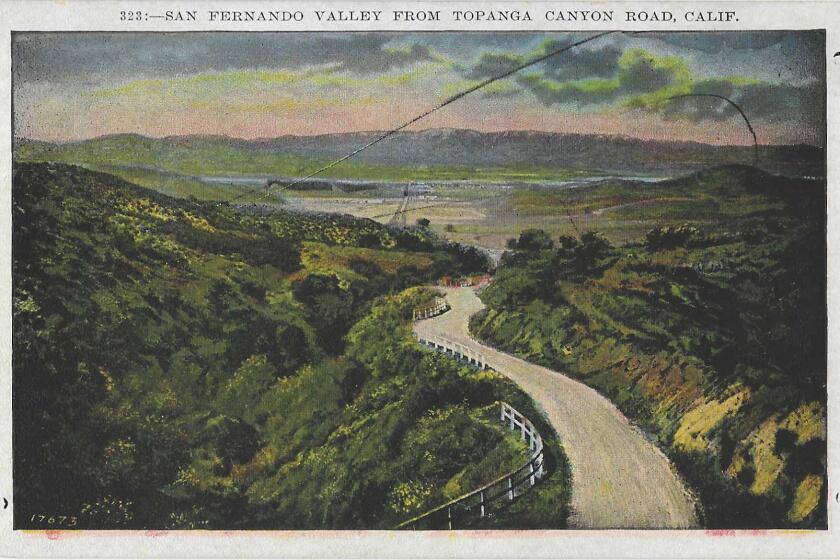

Mt. San Antonio, the tippy-topmost peak in the San Gabriels, might be the only mountain that registers on your retinas from pretty much anywhere around Los Angeles. But you wouldn’t be calling it by that name, any more than you’d be talking about that new album by Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta. No; you’d call her Lady Gaga, and you’d call the mountain Old Baldy or Mt. Baldy.

Just as Lady G.’s parents may be among the few who call her by that quartet of birth names, the official federal list of geographical features strictly uses “Mt. San Antonio.” So does Mt. San Antonio College, in Walnut, which otherwise would hear itself called Mt. Baldy College.

St. Anthony of Padua, San Antonio, was a Franciscan, as were most of the padres of the series of California missions, so that’s where you’ll find the smart money for the origins of the mountain’s name. For generations before then, of course, Native Americans knew it by other names and summered at its cooler altitudes.

For Subscribers

Who are the people behind the L.A. places you know and love?

Yankee Californians have been calling it Mt. Baldy for at least 160 years, since gold miners first came prospecting in the slopes above Azusa. They threw together a mining camp they called Eldoradoville, named for the mythic golden king and kingdom of the questing Spanish conquistadores. In January 1862, Eldoradoville, every last man and pan, was wiped off the landscape in the Old Testament rains that turned thousands of square miles of California into inland lakes.

“Baldy” signifies the bare expanses of rock on the face of the summit, but I also like to think of it in the subtler zoological sense of “bald,” meaning having white markings or coloring, like the white-headed bald eagle, our national bird — and also as in white, like the snow that lingers so long at 10,000 feet.

Whether you’re looking for ocean views or desert landscapes or soaring mountain peaks, Los Angeles offers miles upon miles of strikingly different trails.

Mt. San Gorgonio

San Gorgonio, tallest peak in Southern California, raises itself up 11,500-ish feet in the San Bernardino Mountains, and it too is known by another “old” name — Old Greyback, an homage to its vast granite expanses, and usually spelled British-fashion with an E. In 1898, members of a local history group called the Pioneers disagreed so profoundly as to whether to call it San Gorgonio or Greyback that they had to put off a decision until another meeting. Hard to tell which was named first: the mountain and its pass, or the Rancho San Gorgonio — an outpost of the San Gabriel Mission.

In 1887, a geologist with the state mining bureau wrote to The Times to deplore the proliferation of “old” mountain monikers. “I hope that no fellow hereafter will change the name of Mt. San Jacinto into ‘Old Sharpy’ because it has some sharp peaks.” (I rather like Old Sharpy myself. Hikers, can you make it unofficially so?)

On a fine July day in 1904, a Covina rancher and his cousin undertook the climb up Greyback to collect botanical specimens. As an epic storm encircled the mountain, a bolt of lightning zapped the large, metal-banded magnifying glass the rancher was holding in front of his face at that moment, and reduced him to what The Times, with uncharacteristic relish, called “an almost unrecognizable mass of flesh and bones.”

Who was the saint in San Gorgonio? There were several martyred Gorgoniuses in the Catholic lists; the likeliest candidate for ours is St. Gorgonius of Nicomedia. He worked for the Roman emperor Diocletian, and he more or less outed himself as a Christian when he protested the torture of another Christian on the household staff. In consequence, he shared that man’s fate — flayed, trampled, burned at the stake, grilled on a gridiron. It’s surprising there was anything left of him to be venerated, but until the French Revolution scattered saintly relics far and wide, Gorgonius’ holy body parts were to be found in churches throughout France.

Sherman Way isn’t named for a Civil War general. Tarzana Street is named for, you guessed it, Tarzan. Read on for more San Fernando Valley street namesakes.

Mt. San Jacinto

Mount San Jacinto — the future Old Sharpy — scrapes the Riverside County clouds at 10,834 feet. “Jacinto” translates to “hyacinth,” which is no sissy name. St. Hyacinth is beloved in Poland, and is the patron saint of Lithuania. Hyacinth was a well-educated and well-traveled 13th century Polish priest who is, among other credits, the patron saint of weightlifters. How did this come to pass?

As the Mongols were advancing on Kyiv, St. H. was inspired to an act of divine strength by a voice that told him: “Why dost thou leave me behind? Take me with thee and leave me not to mine enemies.” So he hefted a ginormous statue of the Virgin Mary and walked on the water of the river Dnieper to get it out of harm’s way.

He’s also the patron saint of pierogi, for a loaves-and-fishes miracle of the dumplings. There are two versions, or perhaps two miracles: that after a hailstorm destroyed crops in a Polish town, Hyacinth told people to pray, and the next day, the crops were intact, and the locals made pierogis for the future saint. And/or, Hyacinth was miraculously able to feed pierogi to his famished flock during a siege by the Mongols.

In 1887, or maybe in 1896, the unflaggingly enthusiastic naturalist John Muir, who had gazed upon some pretty spectacular natural sights, stood at the summit at sunrise and decreed that “the view from San Jacinto is the most sublime spectacle to be found anywhere on this earth!”

Generals and outlaws, heroes and villains: L.A.’s parks are named for a colorful cast of characters.

Now, from the spiritual to the secular.

Mt. Lee

Mt. Lee. Doesn’t ring a bell? Sure it does. That big white block-letter sign, H-O-L-L-Y … see? I knew you knew it. You’d think the Hollywood sign would logically be found on the slopes of Mt. Hollywood, but no. The Hollywood sign is on Mt. Lee, a bit of topography now in the embrace of Griffith Park.

And Mt. Lee is named for? Not Spike Lee. Not Bruce Lee. Certainly not Robert E. Lee.

It’s Don Lee, who rose from running a bike shop on Main Street in downtown L.A. to making a tidy sum selling Cadillac LaSalles, then turning to broadcast — first a radio network then a venture in TV. His transmitters stood atop the urban mountain that carries both his name and the Hollywood sign. He died in 1934, before television came into its own. Across the decades, the oversized hill changed hands among folks like the pioneering silent film director Mack Sennett, the developers who raised up the “Hollywoodland” sign, and Howard Hughes.

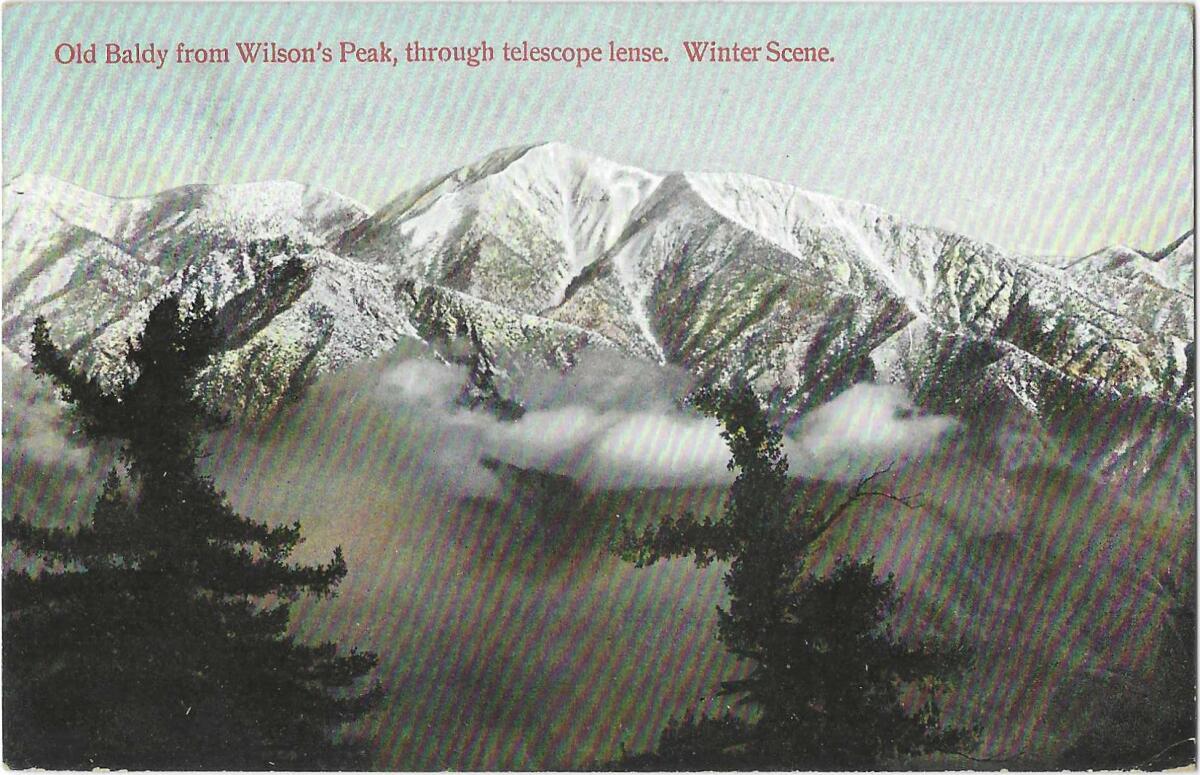

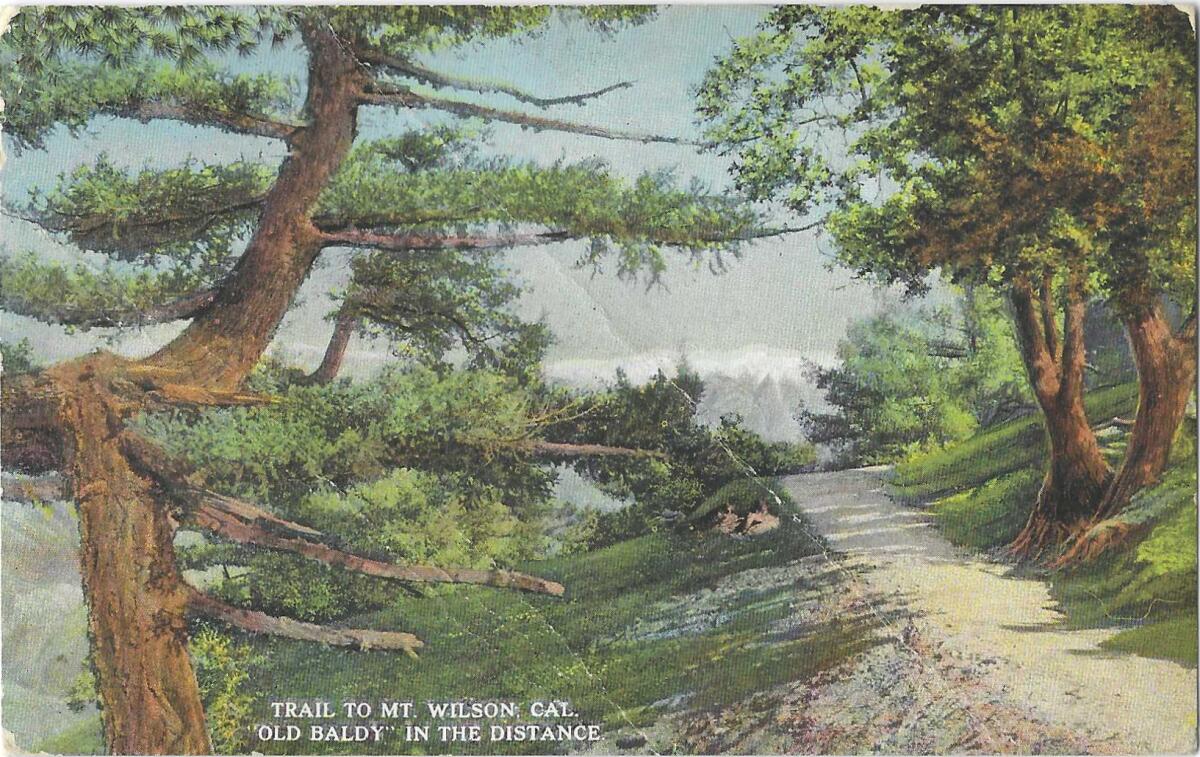

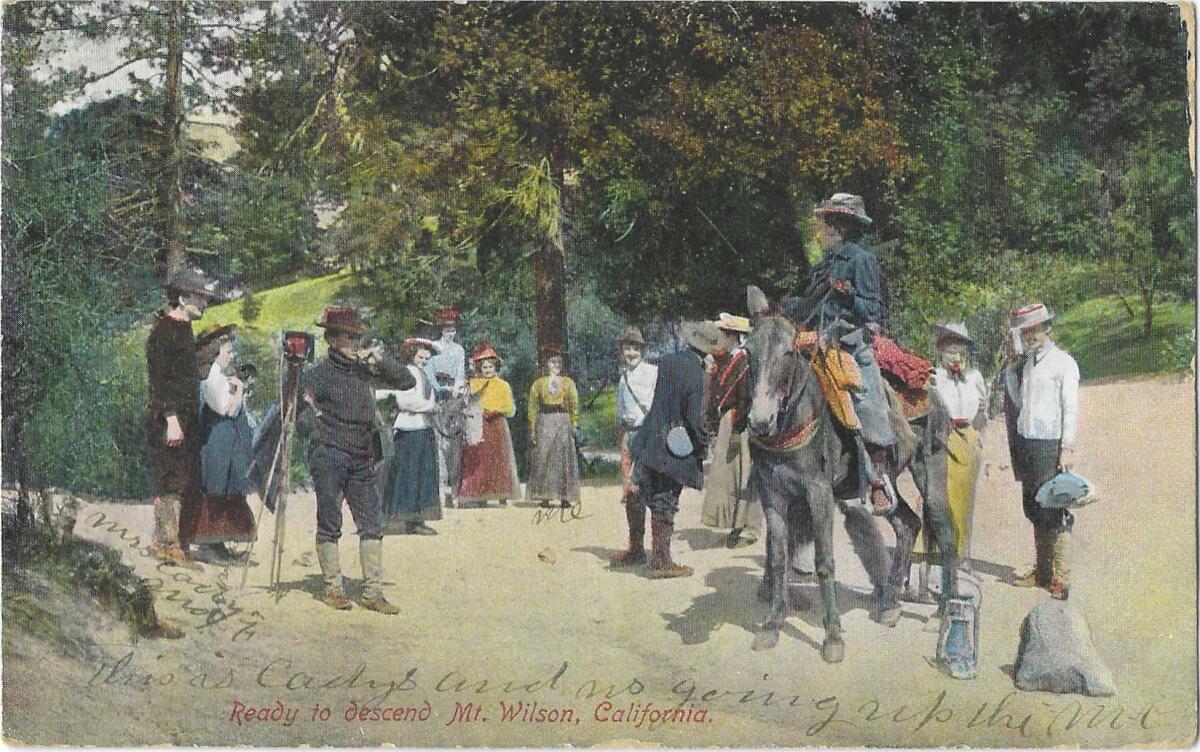

Mt. Wilson

As long as we’re on the topic of transmitters, take a gander at Mt. Wilson. On its top you can see, on clear days, bristling like a peeved hedgehog, a costly copse of transmitters for Southern California TV and FM radio stations and some law enforcement agencies’ communications.

The “Wilson” of Mt. Wilson is Benjamin Wilson — called “Don Benito,” after the fashion of ambitious Yankees who took on a Spanish name as a business and marital emollient in Mexican Southern California.

The mountain took his name sometime after Wilson, in 1864, cleared a trail up its flank to clear timber for his myriad business interests. Over the course of his years here, he ranched, sold and bought land, politicked (as L.A. mayor, county supervisor and state senator), and wrote a study of contemporary local Native Americans.

You may not have heard of him, but you’ve surely heard of his grandson, who spent some of his free time in the family’s San Marino home: Gen. George S. Patton.

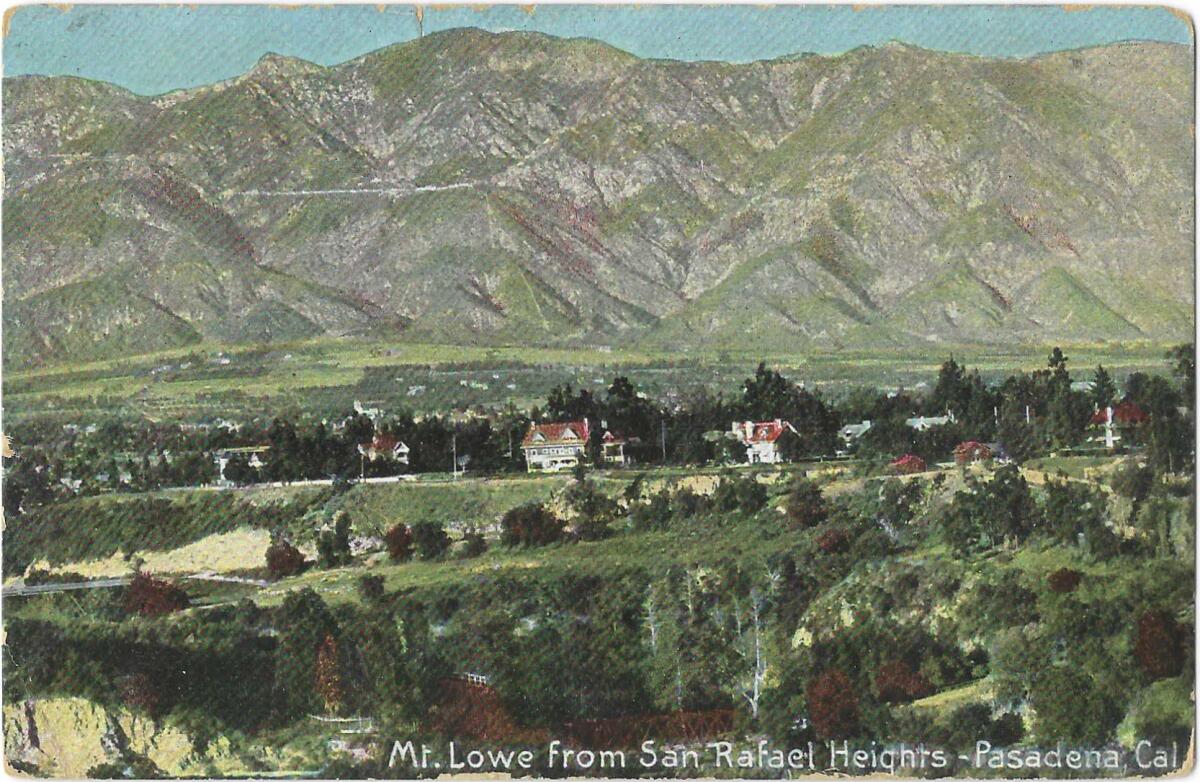

Mt. Lowe

Of Mt. Lowe’s creator, you have read here already — Thaddeus Lowe, balloonist, one of the crackpot-or-genius Californians like Abbot Kinney, the builder of the American Venice. Lowe created a fantasy mountain-peak fun resort and a thrills-and-chills ride to its top. Our Angeleno forebears were remarkably eager for risky and arduous adventures in climbing, riding, trekking, and exploring, all in corsets and Homburg hats.

Mt. Lukens

So many natural features — not just in California but across the nation — bear the names of men with more money than merit, and I am glad to say that Mt. Lukens, in the San Gabriels, bears the name of a man who more than matched this mountain.

Theodore Parker Lukens deserves the nicknames “the father of forestry” and of reforestation. He gave up his post as president of a Pasadena bank to take up the work of conservation and reforestation in the burned-over mountains and canyons of the San Gabriels in the early 1900s. His half-dozen years working with the federal government created a template for replanting and restoration programs. We’re talking tens of thousands of, maybe even a hundred thousand, trees.

Lukens started a tree nursery at Henninger Flats, experimenting with species that could withstand heat, drought and fire. When he went on the rubber-chicken lecture circuit, speaking to bankers’ boards and chambers of commerce, his topics were always water, fire, flood and trees. Muir wrote to him in 1897: “I’m glad the bank is off your back, so now you can go free in the woods. … Write and get others to write to the Senators and to the Secretary of the Interior and make their lives wretched until they do what is right by the woods.”

Mt. Lukens is nearly a mile high, the tallest peak within L.A. city limits. But it wasn’t always called Mt. Lukens. In the 1930s, the board of supervisors re-labeled it from what the locals called it: Sister Elsie Peak. Sister Elsie was a beloved nun of the Sisters of Charity order. She came here sometime after 1850 and set up a school and an orphanage in Tujunga for Native American children. Her name persists on a historic well in Tujunga, and on the Sister Elsie Trail.

Waterman Mountain

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

And the last mountain-and-man duo was originally a woman.

In the spring of 1889 an ardent forester and outdoorsman named Robert B. Waterman, his wife, Liz, a California native, and a friend who went by the splendid name of Commodore Perry Switzer (as in the future Switzer Falls, a beauty spot in the San Gabriels), spent about three weeks going there and back over the mountains from La Canada into the Antelope Valley, climbing right along with the bighorn sheep.

Now, don’t confuse the Robert Waterman of Waterman Mountain with the Robert Waterman of Waterman Canyon. In federal Agriculture Department documents from 1906, the mountain’s namesake is listed as a “forest guard” with an annual pay of $720. The canyon’s namesake was a silver mining magnate who became governor of California and once paid more than 20 times the forest guard’s annual pay for a house in San Diego.

Because Frau Waterman was evidently the first non-native woman to scale those heights, her husband decided that the peak should bear her name. He didn’t name it Liz, or Elizabeth, but “Lady Waterman’s Peak.” They even built a monument of rocks at the summit to mark the event.

Well, as the official U.S. Geological Survey maps got drawn, somehow, somewhy, the “Lady” part disappeared from the map. A $720-a-year forest ranger can scale an 8,000-foot peak, but that doesn’t give him the tallest soapbox. Still, give Bob Waterman credit: He tried for years to get his “Lady” back on the mountain.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Baldy? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.